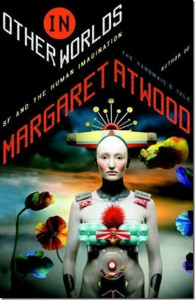

Margaret Atwood needs no introduction to readers of Green Man Review. Suffice to say she is one of the best known and highly respected North American writers of … hmm, well, what is it that she writes?

Margaret Atwood needs no introduction to readers of Green Man Review. Suffice to say she is one of the best known and highly respected North American writers of … hmm, well, what is it that she writes?

Actually, that is exactly the topic she tackles in this collection of some of her writings, mostly non-fiction, about the definition and meaning of science fiction.

Obviously, over the years there has been a certain amount of controversy over what to call the various kinds of speculative fiction, science fiction, and fantasy. And especially over whether it is some kind of insult to classify literary speculative fiction like Atwood’s as SF. I don’t keep up with that sort of thing very much. It’s mostly discussed by the critics and the bloggers and the speakers at symposia and “cons” and the like, and I pretty much steer clear of all of those. I mostly just read what I like and don’t worry too much about what it’s called.

That seems to have been Atwood’s approach when she first started reading sci-fi as a child in post-WWII Canada, which she covers in the first essay, “Flying Rabbits: Denizens of Distant Spaces.” But first, in a lucid introduction, Atwood takes a stab at her own definition of SF, and states the book’s purpose. In doing so, she clears the air of one of the genre’s tea-pot tempests – a mild tiff between herself and Ursula K. Le Guin over why Atwood doesn’t think of her own works such as The Handmaid’s Tale and Oryx and Crake as science fiction. Actually, the air was cleared at a public conversation the two held on stage in Portland, Oregon, in the fall of 2010, an event for which I had tickets but was unable to attend due to personal circumstances. It turned out that the two had almost opposite definitions of the genre. From Atwood’s introduction to In Other Worlds:

What I mean by “science fiction” is those books that descend from H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds, which treats of an invasion by tentacled, blood-sucking Martians shot to Earth in metal canisters – things that could not possibly happen – whereas, for me, “speculative fiction” means plots that descend from Jules Verne’s books about submarines and balloon travel and such – things that really could happen but just hadn’t completely happened when the authors wrote the books. I would place my own books in this second category: no Martians. …

… (W)hat (Le Guin) means by “science fiction” is speculative fiction about things that really could happen, whereas things that really could not happen she classifies under “fantasy.” … In short, what le Guin means by “science fiction” is what I mean by “speculative fiction,” and what she means by “fantasy” would include some of what I mean by “science fiction.” So that clears it all up, more or less. When it comes to genres, the borders are increasingly undefended, and things slip back and forth across them with insouciance.

I didn’t mean to spend so much time and space on the Introduction, but it’s a good illustration of her style and why I like it: clear, logical and laced with wit.

The book has three sections. The first has three longish essays in which she treats on her own history as a reader and creator of tales, the roots of superheroes and fantastic tales in our species’ various mythologies, and our penchant for creating or imagining what she calls “ustopias.” That’s a portmanteau combining utopia and dystopia, because as Atwood points out, every utopia contains its own dark, shadowy underworld and every dystopia at least implies a more-perfect realm from which its inhabitants have fallen.

The second is a collection of Atwood’s own reviews of or musings on science fiction, technology and ustopias, real or imagined. One of the best is her overview of Le Guin’s Ekumen oeuvre, focusing particularly on The Birthday of the World. She also has some serious thoughts about Orwell, Wells, Huxley, and Swift, and writes a beautiful critique of Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go. The third, slightly less satisfactory section comprises short “homages” to various forms of SF, the best of which is “The Peach Women of Aa’a,” a tale told by one character to another in her novel The Blind Assassin.

It’s not a page-turner, or a “necessary” or life-changing book, nor does it break any new ground. But In Other Worlds is a new Margaret Atwood book. And that, for the thoughtful reader, is always something to celebrate.

(Nan A. Talese/Doubleday, 2011)