Michelle Erica Green wrote this review.

Michelle Erica Green wrote this review.

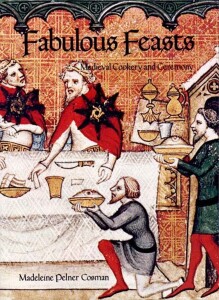

Partly a history of medieval cooking, partly an illustrated guide to the harvesting and processing of food and partly a recipe book, Fabulous Feasts offers – well, to borrow an anachronism, a smorgasbord of pleasures for the reader. Though the text focuses primarily on the English banquet hall, the copious color and black-and-white illustrations originate in Spanish romances, French books of hours, Dutch woodcuts and illuminated Bibles, and the recipes reflect trading across regions in spices and herbs. It’s a beautiful volume that would be worth owning for the illustrations alone.

Beginning with the assertion that “few indicators define a people so well as its foodlore,” Madeleine Pelner Cosman examines what English feasts suggest about the religion, medicine, superstitions, social hierarchy, criminal problems and naughty behavior of long-ago Londoners, as well as mythic meals from such sources as Arthurian romances, The Canterbury Tales and various fables. Feasts (and famine) were central to medieval life, with the marketplace as a central site of social interaction and the husbandry of animals a task that crossed class lines. When grain was not plentiful, there were riots; when food was not properly stored, there were deaths. In better times food could be an art form in itself, sculptured to adorn a great table, or the subject of art, poetry, fiction and history lessons linking the morality of creating fine baked goods to living an upright lifestyle.

This is not a book for historical sticklers. Most of the recipes are undated; few are attributed to any specific source in the detailed bibliography; and a few call for ingredients that were not in wide supply in medieval England. Moreover, it is not a book for inexperienced cooks, for it is taken for granted that the chef will know the proper techniques for broiling meat in a grid iron and making pie crust from scratch. And while you will learn which medieval markets carried all the ingredients for farsed chycken, you may still have trouble procuring ingestible sandalwood for your spiced capon in nutted wine sauce.

After skimming the medieval sanitation laws, you may not find yourself all that hungry anyway. Fabulous Feasts contains ample quotations from historical sources about water waste and sewage, methods of illegal fishing, and the uses of dead animal parts among poorer merchants. Need a list of foods that will make you fart? If you don’t want to wade through Chaucer, you can find excerpts here. You can also find information on “miraculous” foods from mythology and the Bible, including the origins of Passover charoset and the elements of witches’ Sabbaths.

There are details from sumptuary laws, which existed primarily to delineate the classes – the fabrics, furs, belts, badges, trains, and jewelry reserved for aristocrats – but which came to be associated with moral and religious considerations that affected the use of food and particularly drink. The ancient belief that the macrocosm was created of the four elements, earth, air, fire and water, paralleled in the human body as blood, phlegm, choler and bile, determined the combinations of food necessary not only for healthy digestion and disposition, but for spiritual balance and moral rectitude. It was believed necessary to keep cinnamon and cloves on hand not only to flavor bland food, but to keep sinuses and sinews in proper working order.

The recipe section begins with a page of sketches of popular coloring agents (violet, dandelion, mint), followed by brief and incomplete advice about where to find rare ingredients like galingale and cubebs (try natural food stores or Hungarian markets). The author recommends enlisting the help of a butcher in cracking open bones for marrow and advises guests to use traditional implements for eating – i.e., fingers, not forks. After this advice, one finds such delicious and manageable recipes as pears with carob cream, sorrel soup with figs and dates, almond omelettes (amondyn eyroun), and Passover nutcake.

Many of the adaptations of medieval recipes are quite loose – either they use ingredients that were likely not available in medieval Britain, or they call for ingredients that may have been plentiful once upon a time but take some hunting to find in the modern era. If there are modern equivalents for some of the Middle English names for spices and mincemeat combinations, the book doesn’t translate them. Medieval cookery often involved trial and error; few recipes specified exact amounts of sweetening agents or spices, and few kitchens had brass auncers for measurements. Thus this reviewer was far too intimidated to try any of the more sophisticated recipes.

But as luck would have it, my friend Jill came over, noticed the book on my table and exclaimed, “Oh! My ex-husband and I once made the Saumon Pie!” Laughing, she related her experience with the recipe, found in the book on page 172. “This book is so casually written that it looks to non-cooker like it would be easy recipe, but it’s not, and it’s expensive! Before you start, you spend about $50 just for the salmon. You have to make a saffron glaze, which tastes delicious but is like $15 for three little twigs of saffron. Most people probably have cinnamon, cloves, pepper and maybe wine, but you still need figs, pine nuts and currants. And I did not use polarized almonds.”

Jill was traumatized to discover that the recipe called only for “a pie crust – there’s no recipe for an ‘authentic’ pie crust, you have to find your own recipe and make it, at least two hours before you do the rest.” Yet she calls the pie with milk glaze “the best I ever made in my life,” and says, “The entire pie was so delicious and filling, it could serve six people as an entire meal by itself.” She recommends that if you’re going to the trouble of making any of the pies, you should double the recipe and throw a party.

I hadn’t realized that “humble pie” was made from tripe – the intestines and urino-genital tracts of animals – so I’ll try to make certain not to eat any. And I’m going to assume that Four and Twenty Blackbird Pie is supposed to be a joke based on a nursery rhyme rather than something people actually ate; I’m not sure I’ll be able to keep down my rysbred (rice pancakes) otherwise. There’s a certain appeal in the “slender” widow’s meal of milk, brown bread and an egg, now that I know how easily the meat and brews can spoil, especially if stored in wood containers. Still, some indulgent golden figs would be nice, and though I don’t fancy medicinal mead, duck with sauce galentyne, served with good wine and currant dumplings, would sound good in any era.

Cosman’s prose is dense and filled with italicized words from Middle English and other languages. Still, the book is often hilarious, as when she blames the “inadvertent stupidity of individuals and institutions” for the stinking, polluted river water, and when she describes the meals believed to be served in Hell to the damned. For fans of foodlore, Chaucerians, fans of medieval art or brave chefs, Fabulous Feasts will bring many hours of delectation.

(George Braziller, 1976)