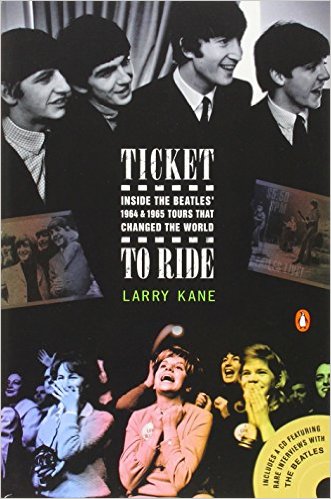

Larry Kane indeed got a ticket to ride. He was the only American journalist in The Beatles’ official press group on their groundbreaking 1964 U.S. tour. The tour changed the way rock ‘n’ roll concerts were played, it changed a lot of people’s minds about The Beatles, and it changed Larry Kane’s life. Nearly 40 years later, he’s finally gotten around to writing about it, in Ticket To Ride. With this book, he joins the legions of writers whose tomes feed the still insatiable appetite of Beatles fans for more about the Fab Four.

Larry Kane indeed got a ticket to ride. He was the only American journalist in The Beatles’ official press group on their groundbreaking 1964 U.S. tour. The tour changed the way rock ‘n’ roll concerts were played, it changed a lot of people’s minds about The Beatles, and it changed Larry Kane’s life. Nearly 40 years later, he’s finally gotten around to writing about it, in Ticket To Ride. With this book, he joins the legions of writers whose tomes feed the still insatiable appetite of Beatles fans for more about the Fab Four.

No pop group had ever made such a tour — 25 concerts in 23 cities in a month, August 19 – September 20, 1964. Starting in San Francisco, they zig-zagged across North America, from Toronto to Dallas, L.A. to New York and back, playing and singing to legions of screaming, hysterical fans. The fans, some as young as 10 years old, some adults, stood in lines outside of stadiums and concert halls for hours and screamed themselves hoarse before, during and after the Beatles’ brief shows. They mobbed the stages, overwhelmed security, chased and sometimes caught the cars carrying their idols. They stood all day and all night in the streets outside the hotels where the band was staying, hoping in vain for a glimpse of the boys. They risked detection, arrest and sometimes life and limb in their attempts to sneak past the security cordons. And at least once, they got their hands on a Beatle in a hotel lobby, tearing off part of Ringo Starr’s shirt and ripping away his cherished St. Christopher medal.

In short, nobody was prepared for the wave of Beatlemania when it hit America.

Kane was there for it all. A 21-year-old news director for a radio station in Miami, Florida, he had covered The Beatles’ brief stay in Florida in February ’64, where they taped an appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. A few months later, when he learned that The Beatles had scheduled a gig in Jacksonville, Fla., as part of their summer tour, he wrote The Beatles’ press office to see if he could get an interview while they were there. Instead, manager Brian Epstein wrote back inviting him to join the entire tour. Shocked, he got permission from management, arranged to syndicate his reports to pay for his room, board and airline ticket, and away he went.

From the perspective of 40 years in the future, everybody recognizes what a cultural phenomenon The Beatles were. But to most adults in 1964, they were just four long-haired boys who sang that noisy rock ‘n’ roll; and although a lot of kids were quite enthralled with them, most of their elders were pretty sure they were a passing fad.

Kane was among the latter group. In fact, he was a bit of a stuffed shirt, although one who was game for just about anything, eventually. He came to not only enjoy the music (he doesn’t seem to have listened to a single song of theirs before the tour), but to realize just what a seismic shift in popular culture they represented. But mostly, he — like everybody who came in contact with John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr — grew to like them immensely as people. They were young, energetic, fun-loving and irreverent, but they were also warm, respectful and big-hearted human beings, says Kane.

Kane’s book takes us from city to city, hotel to hotel, concert to concert on the 1964 tour. There are brushes with celebrities in Hollywood, run-ins with cigar-chomping moguls in the heartland and guards with guns in Dallas, site of the assassination of a President only nine months earlier. And always the fans, and the security. And Kane, lugging his 15-lb. reel-to-reel tape recorder, interviewing the boys in the plane, the hotel room, the dressing room, to feed his daily reports to stations around the country.

He joined The Beatles again a year later for a shorter tour, and lucidly portrays the difference a year made. The Beatles were looser, more relaxed, enjoying everything more. And they were using drugs such as marijuana, uppers and LSD as well. Kane dwells long on the record-shattering performance before more than 56,000 people at Shea Stadium on that tour, the largest audience ever gathered for a musical performance up to that point.

It was a fascinating time, and Kane witnessed it and reports on it. It’s too bad his writing is so stiff and awkward most of the time. In passages like this one, about his feelings after watching the taping of their final appearance on the Sullivan show in ’65, it helps to hear it in your head as though it’s being read aloud by a newsman from the Sixties:

“This ‘newsie’ was continuing his music education, learning how to enjoy it more and even getting a little rhythm. The Beatles magic was picking up where it had left off after the last tour, continuing to work its powers on me. That, as my friends will tell you, was a cultural miracle. The Beatles are back, I thought, as I strolled through New York on the way back to our hotel. And once again, I was in the middle of it. Every day with them would bring something new and adventurous.”

Although Kane noticed that Lennon was high on something before the Sullivan taping, he totally failed to notice that John booted the lyrics on every song he sang that night. He did correctly pick up on the fact that The Beatles were much looser and having much more fun as they played, this time around; John even played the electronic piano with his elbow on Paul’s “I’m Down.” But it wasn’t anywhere near “the performance of (Lennon’s) life,” as Kane calls it.

The most awkward passage in the book is his recounting of the time Epstein made a pass at him — but I can’t imagine writing about such an episode myself, so I’ll give him a pass on that one. And he does write authoritatively about the state of radio in the mid-Sixties, and about the improvements in sound systems as the tours progressed.

Interestingly, the best, most relaxed writing comes in the epilogue, where Kane recounts his later meetings with The Beatles, including a hilarious story about Lennon sitting in for the weatherman at Kane’s Philadelphia TV station in 1975.

Ticket To Ride is a little bit Pilgrim’s Progress, a little bit pop-culture history, and it works if you don’t expect too much of it. It’s nowhere near the worst book written by a Beatles insider, take my word for it, and it’s actually entertaining in many ways. Two nice features are an accompanying CD, with about an hour of Kane’s interviews with The Beatles over the years, and a table showing the dates, places and crowd sizes of each show on the two tours.

Running Press, 2003