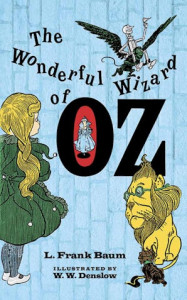

The Wizard of Oz (George M. Hill and Company, 1901)

The Land of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1904)

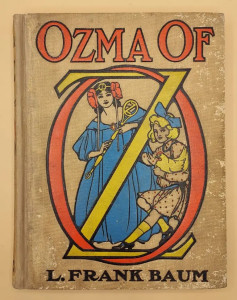

Ozma of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1907)

Dororthy and the Wizard in Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1908)

The Road to Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1909)

The Emerald City of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1910)

The Patchwork Girl of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1913)

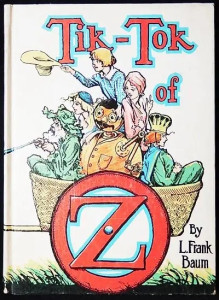

Tik-Tok of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1914)

The Scarecrow of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1915)

Rinkitink in Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1916)

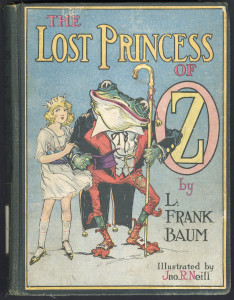

The Lost Princess of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1917)

The Tin Woodman of Oz (Reilly and Britton, 1918)

The Magic of Oz (Reilly and Lee, 1919)

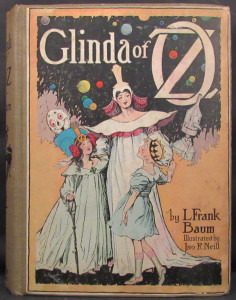

Glinda of Oz (Reilly and Lee, 1920)

L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz is an American icon. Almost immediately on its publication in 1901, it was produced for the stage, and at least four film versions (including several by Baum himself) were made before the famous 1939 Judy Garland production, including one with Oliver Hardy as The Tin Woodsman. Many editions have been published including two that have been previously reviewed in The Green Man Review, The Annotated Wizard of Oz and The Kansas Centennial Edition.

L. Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz is an American icon. Almost immediately on its publication in 1901, it was produced for the stage, and at least four film versions (including several by Baum himself) were made before the famous 1939 Judy Garland production, including one with Oliver Hardy as The Tin Woodsman. Many editions have been published including two that have been previously reviewed in The Green Man Review, The Annotated Wizard of Oz and The Kansas Centennial Edition.

Baum also produced 13 sequels, as well as several other books taking place in Oz’s universe). I have, over the last several years, read all 14 of Baum’s Oz books to my son as bedtime stories and enjoyed every one of them. Indeed, I dare say the original, The Wizard of Oz is middle-of-the pack when it comes to my favorites.

The first sequel The Land of Oz is unique in that Dorothy does not make an appearance in it. Instead, the story concentrates on a Oz boy named Tip, his escape from the evil witch, Mombi, and his adventures thereafter. A second intertwined plot concerns a girl army led by General Jinjur, and their capture of the Emerald City and overthrow of the Scarecrow, who had been left as the King of Oz at the end of The Wizard of Oz. The story introduces Princess Ozma of Oz, who reigns over the remaining books as the ruler of Oz, as well as Jack Pumpkinhead and the animated Sawhorse, who play key supporting roles in later stories.

There were several key developments in The Land of Oz besides the establishment of Princess Ozma. Baum can be seen starting to create more of a history and geography for the land of Oz in preparation for future stories. The look of the illustrations is much different, as well. W.W. Denslow illustrated The Wizard of Oz in a rather simple, cartoonish style. John R. Neill took over the illustrator position for The Land of Oz and would continue to illustrate the stories with a more realistic and, in my opinion, far more pleasant style. All in all, this was a solid outing for the series.

In Ozma of Oz Dorothy returns, only this time by way of a shipwreck while traveling to Australia with Uncle Henry. Accompanied by Billina, the yellow hen, she also makes landfall outside Oz — in fact, only the last two chapters take place in Oz — if still in enchanted territory. Along the way she rescues Tik-Tok, the clockwork man, before meeting Ozma, as well as her old  friends The Scarecrow, The Tin Woodsman, and The Cowardly Lion. The bulk of the story concerns Ozma’s expedition to rescue the royal house of Ev from the clutches of the Nome King, who has transformed them into knickknacks.

friends The Scarecrow, The Tin Woodsman, and The Cowardly Lion. The bulk of the story concerns Ozma’s expedition to rescue the royal house of Ev from the clutches of the Nome King, who has transformed them into knickknacks.

Ozma of Oz fairly well establishes the tone for the rest of the series. Ozma is portrayed as the perfect fairy ruler, Dorothy as the plucky heroine, and a rogues’ gallery of creatures provide support. The stories also start to develop a greater feel of menace and danger, compared to the lighter opposition in the first books. The Nome King will be a recurring in villain in several subsequent novels. Neill finished the transformation of the illustrations with Dorothy portrayed with short, blonde hair, as opposed to the long brown hair of Denslow’s illustrations.

In Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz it is an earthquake that delivers Dorothy, along with her kitten Eureka, her cousin Zeb, and Zeb’s horse Jim into enchanted lands beneath the Earth. However, it is the Wizard who holds center stage in this story, being transformed from the humbug of the original story into a daring, if unconventional, adventurer, able to think his way out of most trouble and be competent with sword and revolver, when wit fails. In the end, he returns to Oz on a permanent basis.

When I first read the Oz books, while my age was still in single digits, Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz was my favorite and it has held up well. The vegetable Mangaboos and their glass city come off as truly alien and are the first of many close escapes for the adventurers. Even Oz is a bit darker, as Dorothy’s kitten, Eureka, is put on trial for her life, for having supposedly eaten a piglet. This is one of the darker of Baum’s stories but it is one of the most satisfying.

In The Road To Oz it does not, for once, take a natural disaster to transport Dorothy to Oz. Instead, in attempting to show a traveler, the Shaggy Man, the road to Butterfield, she finds herself on a magical road that leads to a new set of companions including Polychrome, the rainbow’s daughter, and the perennially lost little boy Button-Bright. Eventually, the road, as per the title, takes her to Oz. The last several chapters are one of the most bizarre of the series, recounting a gigantic birthday party for Ozma characters from a number of other non-Oz stories that Baum had written appearing, including a somewhat secularized Santa Claus.

With Polychrome, The Road to Oz introduces my favorite Oz character. The ever-dancing daughter of the rainbow is described as another of the various  beautiful girls, mortal and otherwise, but, unlike most of Baum’s creations, there is a certain knowingness and sensibility about her — not to mention she throws a punch (OK, a slap) at one point. She appears in only three of Baum’s Oz books, but the rainbow’s daughter is one of the most grounded characters in the series. Her presence in this book makes up for the hideous crash and burn of the party at the end, as Baum goes way over the top in praise of Ozma.

beautiful girls, mortal and otherwise, but, unlike most of Baum’s creations, there is a certain knowingness and sensibility about her — not to mention she throws a punch (OK, a slap) at one point. She appears in only three of Baum’s Oz books, but the rainbow’s daughter is one of the most grounded characters in the series. Her presence in this book makes up for the hideous crash and burn of the party at the end, as Baum goes way over the top in praise of Ozma.

The Emerald City of Oz brings Dorothy, as well as her Uncle Henry and Aunt Em, to Oz for good. The bulk of the story is taken up with two separate plots. The main one has Dorothy and company touring Oz and seeing many of the stranger — and often quite surreal — communities in it. The secondary plot brings back the Nome King, as he creates a villainous alliance in attempt to invade and conquer Oz.

The contrast works rather well as Baum manages to make the threat to Oz seem serious, although the solution is a little too pat. This was intended to be the last book of the Oz series, as it concluded with Glinda casting a spell to make Oz invisible to the outside world and Dorothy sending a note to Baum stating “You will never hear anything more about Oz, because we are now cut off forever from all the rest of the world.”

But of course this wasn’t the end. Demand for more Oz stories led to The Patchwork Girl of Oz with the excuse that they were communicating from Oz to Baum by radio. This story takes place entirely within Oz, as a Munchkin boy, Ojo the Unlucky, searches for a way to turn his Unc Nunkie back from being a statue with the help of Scraps, the just-brought-to-life Patchwork Girl, Bungle, the Glass Cat, and a square creature known as a Woozie. He is later joined by Dorothy, The Scarecrow, and Toto.

On the one hand this is a fun romp. Patches is one of the funniest, most sarcastic characters in the Oz series. There are some amusing turns, including an annoying animated phonograph and the unintentional humor of radium being portrayed as one of the healthiest substances in the world.

On the other hand, there are some rather disquieting elements in The Patchwork Girl of Oz. For one thing, it is strongly established here that the only people allowed to use magic in Oz are Glinda, the Wizard, and Ozma; private use of magic — such as created The Patchwork Girl — is forbidden. More seriously disturbing is the treatment of Bungle. Initially, the glass cat is vain about her visible pink brains. At the end of the novel, Ozma has replaced the pink brains with transparent one so that the cat acts in a more docile manner. In a later book, the Glass Cat has her pink brains and her vanity back, but, when I read this to my son, I made it clear to him that I thought Ozma had made a serious error in her actions towards Bungle. Oz’s utopia looks somewhat dystopian in The Patchwork Girl of Oz. I am not sure whether Baum meant it that way though.

Tik-Tok of Oz has three intertwined plot strands. The first is the attempt of Queen Ann Soforth of Oogaboo, the smallest and poorest kingdom in the land of Oz, to conquer Oz — a campaign that immediately goes in the wrong direction, thanks to Glinda’s attentiveness. The second strand is the  Shaggy Man’s search for his brother, who is being held captive by the Nome king. The third is the arrival of Betsy Bobbin and Hank the Mule in the lands bordering Oz, by way of shipwreck. As for the title character? Tik-Tok doesn’t appear until chapter seven and takes only a secondary roll in the story.

Shaggy Man’s search for his brother, who is being held captive by the Nome king. The third is the arrival of Betsy Bobbin and Hank the Mule in the lands bordering Oz, by way of shipwreck. As for the title character? Tik-Tok doesn’t appear until chapter seven and takes only a secondary roll in the story.

This is one of the more grown-up stories in the Oz series. There is nothing inappropriate for children, but there is a romantic subplot, a theme not present in the previous stories (except maybe The Scarecrow and Patchwork Girl in the previous novel). Polychrome returns, acting sensibly, when everyone else doesn’t. The biggest problem is that Betsy Bobbin comes off as a rather unintelligent girl and does not live up to the Dorothy standard. All and all, it’s a run-of-the mill novel for the Oz series — but that makes it still quite good.

Tiny Trot and Cap’n Bill had been the heroes of several non-Oz adventures that Baum wrote. In The Scarecrow of Oz they find themselves shipwrecked (that device, again) and transported to the lands outside Oz. They are joined by Button-Bright, who had been in one of Trot’s previous adventures and has grown up a few years since The Road to Oz. Eventually, they find their way to Jinxland, an isolated kingdom within Oz, where the traditional fairy tale of a prince disguised as a gardener’s boy and the princess he loves. As for the Scarecrow, he does not make his first appearance until halfway through the novel and serves in a rather deus ex machina role to the main characters.

If anything, The Scarecrow of Oz suffers from having to be an Oz novel. Trot and Cap’n Bill make a good pair of heroes in their own right, who should not need rescuing and up until the Scarecrow’s arrival, it is a fun adventure. After that, the Scarecrow, backed by Glinda and Ozma’s power, make the story too pat.

Rinkitink In Oz is one of the best but most frustrating of the Oz novels. It scarcely is an Oz novel with all of the action and almost all of the story taking place outside Oz and involving main characters who have not previously appeared in the series. The Island of Pingaree is attacked and all the population, including the king and queen, taken into slavery, except for Prince Inga. With the merry King Rinkitink and the ill-natured talking goat Bilbil, the prince proceeds to rescue his people and attempt to free his parents.

On the one hand, Rinkitink in Oz is grand adventure in classic fairy tale or fantasy style. Prince Inga is an excellent boy-hero — brave, resourceful, and all that good stuff — and grows stronger as the novel progresses. Special credit must also be given to Baum for making the fairy tale archetype of pointy-toed shoes not just stage dressing, but a small (but key) device to advance the plot. The frustrating bit is that, instead of Prince Inga succeeding on his own, Dorothy and Wizard arrive out of Oz to take care of the last problem for him, then whisk him off to one of Ozma’s banquets. The result is an unsatisfying ending to an otherwise marvelous book.

The Lost Princess of Oz is a mystery, opening with the magic items belonging to Glinda, the Wizard, Dorothy, and Ozma disappearing, along with Ozma herself. Several search parties are formed and the story follows the one comprised of Dorothy, the Wizard, and several other characters. This rather resembles The Emerald City of Oz, as the party journeys through Oz, visiting several very strange cities on their way. The story also follows the adventures of Cayke the Cookie Cook, whose magic dishpan has been stolen.

This is a fine romp and a nice mystery, as far as the Oz books go. Baum puts more emphasis on the animals, including Toto, the Cowardly Lion, and the Sawhorse, in the party than he does in other stories, something that I wish he’d done more of. Button-Bright is used well, playing a key part and the Patchwork Girl also is in fine, sarcastic form in The Lost Princess of Oz.

Unlike in Tik-Tok of Oz and The Scarecrow of Oz, the eponymous character of The Tin Woodman of Oz appears in the first chapter and is a  main character. The novel starts with the Woodman recounting how he became tin, as the result of a curse put on him by a witch for loving the witch’s servant, Nimmie Amee. When the Woodsman realizes he never went back to see how his former love was doing (it turns out the Wizard gave him a kind heart, not a loving one) he sets out, along with Woot and the Scarecrow to find what has become of her. Along the way, they are joined by Polychrome and theTin Soldier whose history is much like the Tin Woodman’s.

main character. The novel starts with the Woodman recounting how he became tin, as the result of a curse put on him by a witch for loving the witch’s servant, Nimmie Amee. When the Woodsman realizes he never went back to see how his former love was doing (it turns out the Wizard gave him a kind heart, not a loving one) he sets out, along with Woot and the Scarecrow to find what has become of her. Along the way, they are joined by Polychrome and theTin Soldier whose history is much like the Tin Woodman’s.

There is another deus ex machina rescue in The Tin Woodman of Oz, in the form of Dorothy and Ozma. However, this time, it comes in the middle of the story. The rest is solid adventure, during much of which the heroes have been transformed into bodies not their own.

The center of The Magic of Oz is a magic word: “Pyrzqxgl.” This word, when pronounced correctly, can transform anyone into any other form — and in this story, near about everyone gets transformed after Kiki Aru, who learned the word from his father, meets up with the former Nome King. Meanwhile, various friends of Ozma set out to find unique presents for the fairy princess who has everything.

This story has one of the more fearsome sequences in the entire series: Trot and Cap’n Bill, in their quest to bring home an enchanted plant that blooms every flower, end up literally rooted to the island the flower is on. It’s also interesting to see the talking animals of Oz in the forest where they live. And yet, there is something insubstantial about the story, more a shuffling of forms than an actual adventure. Still, even as a weaker entry in the series, it has its charms.

The final of Baum’s Oz books was Glinda of Oz, published posthumously in 1920. The novel has a feel of science fiction, as Ozma and Dorothy intercede in a war between the Flatheads and the Skeezers, only to find themselves trapped beneath the dome of a submersible island with Glinda and the Wizard leading the rescue. There are also more than a few fairy tale transformations, and many creatures including the Flatheads, who keep their brains stored in cans.

There is still much magic, but the presence of the domed city, submarines, retractable bridges, and the like, gives Glinda of Oz a comparatively 20th century feel that was not present in the previous works. The danger also feels more serious — after being untouchably safe through many of the books Dorothy and Ozma are again in danger of being trapped forever. Baum’s final work is one of his finest.

There have been many editions of The Wizard of Oz. At this writing most, if not all, of Baum’s books are available from Dover Press.

The official Oz series did not end with Baum’s death. Ruth Plumly Thompson would outdo Baum with nineteen “official” Oz stories; several other authors including illustrator John R. Neill, would contribute another six to make forty official Oz novels — not to mention a number of other unofficial Oz novels. Still, Oz is L. Frank Baum’s creation and, with the possible exception of Judy Garland, it is he who is first thought of when one thinks of Oz. There is a lot more than just The Wizard of Oz to thank him for.