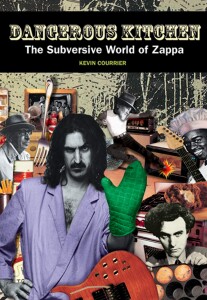

There have been many books written about Frank Zappa. Perhaps the most disappointing, and yet most enlightening, was his own The Real Frank Zappa Book. A bizarre but strangely readable book was Ben Watson’s Frank Zappa’s Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play. Dangerous Kitchen: the Subversive World of Frank Zappa falls somewhere in between. Kevin Courrier is a journalist and film critic for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. This is his second book, and it is a labor of love.

There have been many books written about Frank Zappa. Perhaps the most disappointing, and yet most enlightening, was his own The Real Frank Zappa Book. A bizarre but strangely readable book was Ben Watson’s Frank Zappa’s Negative Dialectics of Poodle Play. Dangerous Kitchen: the Subversive World of Frank Zappa falls somewhere in between. Kevin Courrier is a journalist and film critic for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. This is his second book, and it is a labor of love.

Zappa was a severe critic of modern life. He hated the hippie ethos as much as he hated middle class conformity. He felt people should be themselves, make their own decisions, live with their own mistakes. He was opposed to drugs and alcohol, because he felt music could alter the mind far more effectively. He was perhaps America’s foremost political and social critic for a couple of decades, but he wasn’t taken seriously by many because of the way he looked, or the humor he brought to his critiques.

Courrier obviously admires Zappa a great deal. He has provided a clear, chronological history of Zappa’s career, with critical appraisals of each of his albums from Freak Out through Everything Is Healing Nicely. That’s over thirty years of music and comment. Courrier doesn’t simply accept everything that Zappa released as the work of genius (although he’s quite keen on the hard compositions that many people have trouble with) but he does try to find good in every era, and album. That’s not a bad thing.

Many of Courrier’s opinions reminded me of how I felt, or what I thought, when I first heard these albums. I recall seeing the young Frank Zappa playing a bicycle wheel on an episode of Steve Allen’s talk show. Courrier relates the whole story behind this appearance. He describes Zappa’s early years growing up in California as his father moved from job to job working on airplanes and the guidance system for Atlas missiles. He talks about Zappa’s school days; he was not a particularly good student, as one might imagine. And he describes Zappa’s early days in music, playing “Louie, Louie” in garage bands.

Zappa was influenced by some of the most avant-garde composers of the 20th century: Satie, Schoenberg, Webern, Stravinsky, Ives and Varese. It was difficult for the rock/pop music world to fathom a “rock” musician with influences this deep and obscure. His record labels continually tried to force him to just play rock music, but Zappa soldiered on and won acclaim for his orchestral compositions. Courrier covers these excursions in some depth.

The lyrical content of a typical Zappa album was sure to offend somebody in the audience, but he was consistently funny and honestly caring about modern society. Courrier makes this clear. Maybe he forgives too many of Zappa’s excesses, but he does so in the name of art. There is an intriguing passage about the importance Zappa’s social commentary played for people who were seriously repressed. His second album, Absolutely Free, had been “smuggled into the [Eastern Bloc] within a year of its 1967 release…Milan Hlavsa, a Czech rock star, was the co-founder of that underground band, Plastic People of the Universe. They supported various dissidents, including Vaclav Havel, during the ’70s and ’80s. The band was arrested in 1976, inspiring the formation of the human-rights group Charter 77 the next year. It was perhaps ironic that the two bands who became important symbols for democracy in Czechoslovakia in those years — the Mothers of Invention and the Velvet Underground — absolutely loathe each other.” Later, Vaclav Havel would, as president of the new Czech Republic, attempt to arrange a trade agreement not with the US government but through Frank Zappa! This arrangement lasted only as long as it took to get an American government representative to Prague. “You can do business with the United States or you can do business with Frank Zappa.” After this ultimatum, Zappa’s position was down-graded to unofficial emissary of culture.

Courrier has provided an eminently readable volume that covers every aspect of Zappa’s life. He covers the albums one song at a time; he provides brief biographies of all the musicians who came and went through Zappa’s bands. He is respectful, but maintains enough distance that the reader can still make up his or her own mind about Zappa’s achievements. There is a photo section in the center of the book, but it occurs to me now that I skipped right over it… the text was far more interesting. I remember hearing Frank Zappa on the radio. He was being interviewed by a local late night personality. The question was presented after a long preamble designed to demonstrate the host’s depth of knowledge and heavy “coolosity” factor. Zappa took this in his stride. He took a breath, and put the announcer down with a simple, “Well that’s just the kind of question I’d expect from a cool, cool super-cool major market disc jockey.” He answered the question… it doesn’t matter what it was… but he took no guff from anybody. He was his own man. He took on the music establishment. He took on society. He took on the U.S. government, but he finally met his match when he faced prostate cancer. He passed away in 1993. Dangerous Kitchen is a tribute to a life well lived.

(ECW Press, 2002)