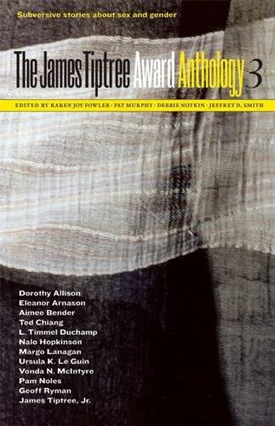

Anyone experiencing art, particularly with the goal of commenting on it, inevitably faces a quandary: how much of the meaning was the intent of the artist, and how much was supplied by the audience? This observation is particularly relevant to The James Tiptree Award Anthology 3: as you will doubtless remember from previous comments, the Award goes to stories that “explore and expand gender.” Mostly in science fiction, but. . . .

Anyone experiencing art, particularly with the goal of commenting on it, inevitably faces a quandary: how much of the meaning was the intent of the artist, and how much was supplied by the audience? This observation is particularly relevant to The James Tiptree Award Anthology 3: as you will doubtless remember from previous comments, the Award goes to stories that “explore and expand gender.” Mostly in science fiction, but. . . .

And there’s part of the quandary.

The relevance is really multifold. Largely a phenomenon of the science fiction/fantasy milieu (the Award’s birthplace and original home was WisCon, although it’s now grown up and has its own place and even a bank account), it is still pretty much identified with that area, although, much like the genres from which it sprang, the requirements for inclusion more or less resist definition. James Tiptree was, after all, a science fiction writer, but as co-editor Jeffrey D. Smith points out in his introduction, the awards have included sf stories by mainstream authors, mainstream stories by sf authors, and slipstream stories, which defy categorization anyway. I should also point out that “stories” in this context is used in its widest sense — a number of novels have won the award, as well.

There is also the way in which stories explore gender, which is not always so straightforward. Geoff Ryman’s “Have Not Have,” which leads off this year’s collection, takes somewhat roundabout aim at the question through a deft and subtle examination of a future fashion consultant in the last village on earth to go online that leaves us with an uncomfortable realization of how too many women still find their identities.

Beauty-as-identity seems to be an overall theme in this collection. Ted Chiang’s “Liking What You See” revolves around how our perception of physical beauty affects our behavior, particularly in the realm of advertising, which also underlies the story by Tiptree, “The Girl Who Was Plugged In.”

Another measure of a woman’s identity (and, for reasons upon which I will not speculate, the overwhelming thrust of this year’s anthology is gender as reflected in women’s identity) is tied intimately to children and family. Aimee Bender’s “Dearth” explores the feelings that can be engendered by a pot of potatoes, while LeGuin’s “Mountain Ways” explores — and subverts — the concept of “traditional” marriage. Eleanor Arnason has her own take on parenting in “Knapsack Poems”: just how does one raise a child with only one body? And how much can one love such a freak?

Stepping back for a broader view, “identity” is really the core theme here, not only for the stories but for the non-fiction selections as well. The topic veers into race with Pam Noles’ “Shame,” an extended commentary on how Ursula K. LeGuin’s deft and subtle introduction of “brown people” into fantasy in Earthsea was subverted when the story hit Hollywood. And then race and gender blend in Dorothy Allison’s treatment of the fiction of Octavia E. Butler, “The Future of Female.” L. Timmel Duchamp’s “Letter to Alice Sheldon” treats of how the sex of the writer affects the interpretation of the work, another reflection of our basic quandary.

As expected, the writings in this volume are excellent, as well as being challenging. It’s hard to pick out favorites, so I won’t try. Just get the book and read them all.

(Tachyon Publications, 2006)