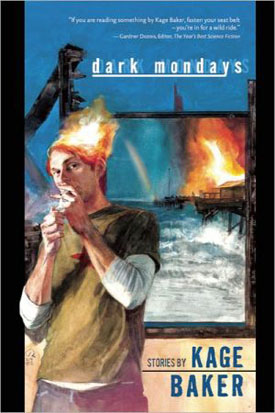

Most people know Kage Baker from her novels and stories of the Company, those wonderful folks who discovered time travel and put it to their own uses. Sadly to say, I only recently encountered the Company. Then her newest story collection, Dark Mondays, crossed my desk. Baker is an extraordinary storyteller who refuses to let herself be bound by the expectations of genre, as the stories here show. In fact, on the basis of this collection, I think I would just call Baker a slipstream writer and not try to get any closer to a categorization of her work (“slipstream” being the genre that wasn’t, according to some people).

Most people know Kage Baker from her novels and stories of the Company, those wonderful folks who discovered time travel and put it to their own uses. Sadly to say, I only recently encountered the Company. Then her newest story collection, Dark Mondays, crossed my desk. Baker is an extraordinary storyteller who refuses to let herself be bound by the expectations of genre, as the stories here show. In fact, on the basis of this collection, I think I would just call Baker a slipstream writer and not try to get any closer to a categorization of her work (“slipstream” being the genre that wasn’t, according to some people).

Take, for example, “Monkey Day,” in which a boy invents a holiday as a school assignment. It’s a story about the power of belief, whether that belief springs from faith or from rational inquiry, and before it’s done it involves a boy, a priest, King Kong and a no-nonsense schoolteacher with a somewhat battered Volvo.

On the other end of the spectrum is the opening story, “The Two Old Women,” which takes place in a fishing village somewhere in North America — it could be Maine or Massachusetts, Nova Scotia or even Newfoundland — and tells a story of love lost and regained, the merciless sea, and a bit of witchcraft.

There are more, and each one, as Bruce Sterling wrote in 1989 column about slipstream, “makes you feel very strange.” They are manifestly not “mainstream,” but I’m not sure you can call them science fiction. There is some of the surreality of magical realism, but not always. They wander around, sometimes just slightly weird, sometimes seeming to be more fantasy than science fiction, sometimes more science fiction than fantasy, sometimes not really either, usually somewhat mordant, a little dark, but often very funny, even lighthearted. They are not, however, always terribly straightforward.

And, while there’s not a story in the book that is less than excellent, the real tour de force, to my mind, is the novella “The Maid on the Shore,” about Captain Henry Morgan, scourge of the Spanish treasure fleets, and his march to take Panama. It’s told as the story of John, who gives his name as “John James” when he signs up with Morgan, another young man who fled England for the Caribbean to escape the gallows. He’s not a bad man. He just screwed up. There is a young woman involved, who may be Morgan’s goddaughter, or his natural daughter, or may not be a natural creature of any sort. It’s a mesmerizing story, which gives me a clue as to how Baker does it.

She’s a strong writer. Just in the way she puts words together, lining them up, putting them through their paces in such a way that we are never aware of the artistry involved, she reveals an exceptional talent behind her finely honed craft. She is one of those who pulls you into a story and keeps you there, effortlessly. Her characters, from Tia Adela, who knows how to bring her husband back from the sea, even though he’s been dead these many years; to Patrick, who wants to observe Monkey Day even if he did make it up himself; to the anonymous and long-suffering narrator of “So This Guy Walks Into a Lighthouse,” who had his much treasured solitude broken in an intolerable way; to John and Captain Morgan, all are deftly rendered, fully developed, living breathing people. And she moves easily from contemporary Hollywood to the Caribbean of the seventeenth century, with many stops in between, so that the stories are not only about a particular time, but become of that time.

If you know Kage Baker’s work, I’m sure you’ve got this one. If you’re not, what are you waiting for? (Note: The title story, “Dark Mondays and Peculiar Tuesdays,” is available only in the limited edition of the collection. Night Shade Books can be found online here.

(Night Shade Books, 2006)