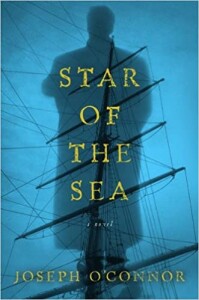

Star of the Sea is the ironic name of a leaking, creaking hulk of a ship that is making its last crossing of the Atlantic, with a handful of first-class passengers and a belly full of the dregs of Europe, destitute Irish people fleeing the horrors of famine. Joseph O’Connor’s masterful novel of the same name is the story of that fateful crossing and the intertwined lives of the passengers.

Star of the Sea is the ironic name of a leaking, creaking hulk of a ship that is making its last crossing of the Atlantic, with a handful of first-class passengers and a belly full of the dregs of Europe, destitute Irish people fleeing the horrors of famine. Joseph O’Connor’s masterful novel of the same name is the story of that fateful crossing and the intertwined lives of the passengers.

The year is 1847, and among the characters we’ll come to know on the crossing are David Merridith Lord Kingscourt, his wife Laura, their servant Mary, the ship’s captain Josias Lockwood, a hobbling Irishman named Pius Mulvey, and American journalist Grantley Dixon, whose fictional memoir makes up the novel.

We know from nearly the outset that someone is killed on this voyage, but we don’t know until near the end who is the victim and who is the killer. But *Star of the Sea* is hardly a whodunnit. It’s a gripping tale indeed: we follow the ship day by day on its perilous winter crossing. The story is told from various points of view, including the captain’s log, letters from or to or about various passengers, and through Dixon’s eyes as he puts the story together some 40 years after these events, after nearly every other survivor of the trip is dead. The details of the voyage are interspersed with these other documents, which look both backward and forward in time, a device which at times helps the reader piece together the tale, and at times obfuscates meanings.

The genesis of folk songs and how they are adapted to fit the needs of the moment is one of many ingenious plot devices O’Connor weaves through his narrative. We’re given to believe that the young Pius Mulvey wrote the song that has come down to us as “Arthur McBride.” In Mulvey’s original version, he and his brother are working their failing farm when they’re visited by a recruiter for the English Army, who offers them escape from their toil and cash money if they enlist.

“Myself and my brother were scratching the land,

When up came a captain with gold in his hand…”

As Mulvey travels around Ireland singing for tips and beers, we see the song take on a life of its own, and begin its transformation into the anti-British, anti-army broadside we know today, in which “me and my cousin, one Arthur McBride,” give the captain and his mates a good drubbing.

This and other details of the stories of Mulvey, Dixon, the Merridiths and others are fodder for O’Connor’s theme: the way colonialism, slavery and class oppression dehumanize both ruler and ruled.

Both Merridith and his wife are English nobility, but their families have lived on Irish soil for centuries. Merridith has nothing but tortured relationships: with his wife, his father, his sons, the servant Mary, Dixon, the starving tenants of his family’s farm, and most of all with his own conscience. Merridith, who we come to know as a mostly sympathetic character, lashes out at everyone near him, particularly Dixon, who is having an affair with his wife and whose nascent socialistic views he abhors.

Mulvey and Mary represent two different sides of the sufferers of the Irish potato famine: the former an amoral survivor whose ramblings take him on an ever-downward spiral of drunkenness and crime; and the latter a noble victim who attempts to uphold her society’s values but who nevertheless is ground down along with those of Mulvey’s ilk.

Dixon, of course, represents the brash New World, those loud and often self-righteous Americans who put down the ways of the Old World and its aristocrats, but have their own guilt to deal with in the form of slavery and the Indian wars.

But they’re not cardboard figures, these characters. O’Connor has made them flesh-and-blood people, complete with nobility and savagery, cunning and caring, black, white and all shades of gray in their hearts. The exception is Merridith’s wife, who is seen as noble, good and long-suffering — but that, of course, reflects the love Dixon, the narrator, feels for her.

Star of the Sea is an education into the enmeshed histories of England, Ireland and America, and a polemic on the evils of serfdom and exploitation. It’s also a rousing good yarn, full of lively, multi-dimensional characters, vivid historical details and colorful language.

(Harcourt, 2003)