What makes reviewing this book complicated is the difficulty in discerning whether the campy, cliché-ridden, pulp-ishness of the book is intentional as an homage to earlier adventure novels, or simply an example of the standard of writing that is normally applied to multi-author paperback fantasy series, such as the Dragonlance, Forgotten Realms, or Halo series. Unnatural History is an instalment in Abaddon’s Pax Britannia series, a series written by several different authors, the only connection being the stories take place in an alternate Earth.

What makes reviewing this book complicated is the difficulty in discerning whether the campy, cliché-ridden, pulp-ishness of the book is intentional as an homage to earlier adventure novels, or simply an example of the standard of writing that is normally applied to multi-author paperback fantasy series, such as the Dragonlance, Forgotten Realms, or Halo series. Unnatural History is an instalment in Abaddon’s Pax Britannia series, a series written by several different authors, the only connection being the stories take place in an alternate Earth.

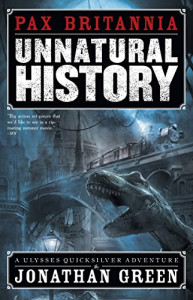

This novel reads like pulp from top to bottom. The book takes place in an alternate 1997, one in which Queen Victoria and the British Empire are still alive and in control (through means not explained until the end), dinosaurs still exist, dandies still sport waistcoats and cravats while exploring Britannia-owned colonies on both the Moon and Mars, and of course, all the important people have ridiculously melodramatic names.

To accurately describe the plot requires a number of exclamation points. Our hero is Ulysses Quicksilver (our gentleman adventurer!), recently returned from a trip to the Himalayas that was thought to have killed him. While his gambling-addict brother Barty is less than pleased, his butler Nimrod (the loyal and quick-thinking servant!) is glad things might return to normal. Ulysses’ employer, Uriah Wormwood (a man with a taste for power!) quickly puts him back to work investigating a break-in at the London Museum of Natural History that resulted in the murder of a night watchman and the disappearance of biologist Dr. Galapagos (a madly brilliant scientist!). Galapagos’ daughter Genevieve (a dainty damsel! Or is she?!) believes whoever stole the device containing her father’s notes and information might just have kidnapped him, too.

Of course, what Ulysses ultimately discovers in his investigation includes cavemen, a de-evolving serum, rampaging dinosaurs, underground bomb factories, traitors to the crown, a scheming villain who refuses to stay dead, and a grand finale involving the Tower of London and a giant zeppelin. Green’s writing style evokes clichés practically non-stop (one whopper of a sentence on page 57 piles on more than one: “Maybe it was something about being a Quicksilver, but Ulysses simply couldn’t resist a pretty face, and when that pretty face belonged to a damsel in distress it made any attempt at resistance even more futile.”), but he also shows real flair for dramatic action sequences (the aforementioned dino-rampage and grand finale are vividly detailed) that suggest more than anything that the overdone pulp writing style might be intentional.

The format means that (except for the frequent pauses for sufficient eye-rolling) the book is a relatively quick read, and the language (if familiar) is at least polished. At face value, the novel is entertaining, but if the next books in the series follow this one’s example, the cheeky “you-haven’t-seen-the-last-of-me!” tone will grow tiresome pretty quickly. While there is style, and a lot of flash, Jonathan Green’s contribution to the Pax Britannia series possesses very little substance.

(Abaddon, 2007)