El Iskandriya sits at the Delta as she has done for thousands of years, a city of great wealth, staggering poverty, intrigue, indolence, and, because she is technically a free city open to the currents of influence from the lands of the infidel, a hotbed of questionable ideas. Into this mix comes Ashraf al-Mansur, known as Ashraf Bey, a well-connected if impoverished artistocrat who shortly before the beginning of his story was a small-time street tough in Seattle. In some manner, involving the liberal application of large amounts of money, Raf, who thought of himself at that point as ZeeZee, was “escaped” from a correctional/rehabilitation center and provided with a diplomatic passport and a one-way ticket to Iskandriya, where he found family, of a sort, and an occupation, of a sort. He mostly spends his days on the patio at Le Trianon, the cafe below his office, where he consumes vast quantities of cappuccino and observes the world from behind a pair of Armani wrap-arounds. The time spent at the cafe is because his job is a sinecure; the wrap-arounds are because his eyes are extraordinarily sensitive to light, which is not the only way in which he is different from most people.

El Iskandriya sits at the Delta as she has done for thousands of years, a city of great wealth, staggering poverty, intrigue, indolence, and, because she is technically a free city open to the currents of influence from the lands of the infidel, a hotbed of questionable ideas. Into this mix comes Ashraf al-Mansur, known as Ashraf Bey, a well-connected if impoverished artistocrat who shortly before the beginning of his story was a small-time street tough in Seattle. In some manner, involving the liberal application of large amounts of money, Raf, who thought of himself at that point as ZeeZee, was “escaped” from a correctional/rehabilitation center and provided with a diplomatic passport and a one-way ticket to Iskandriya, where he found family, of a sort, and an occupation, of a sort. He mostly spends his days on the patio at Le Trianon, the cafe below his office, where he consumes vast quantities of cappuccino and observes the world from behind a pair of Armani wrap-arounds. The time spent at the cafe is because his job is a sinecure; the wrap-arounds are because his eyes are extraordinarily sensitive to light, which is not the only way in which he is different from most people.

He’s already caused trouble by refusing to marry his designated bride, Zara, the daughter of an ex-gangster turned filthy rich businessman. It’s a not-unusual arrangement: Zara’s money for the al-Mansur name and respectability. Raf knows Zara doesn’t want to marry him, so he simply refuses the deal. Then someone murders his aunt, who had made the arrangement, and things start to get difficult, not the least because he is one of the prime suspects.

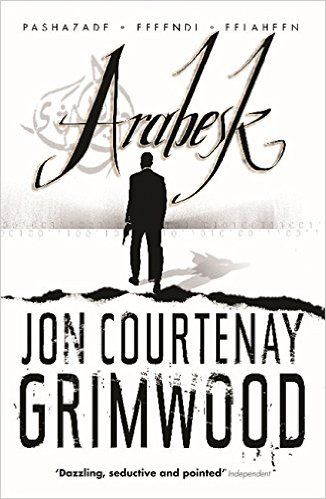

Jon Courtenay Grimwood’s novels are generally termed “science fiction,” which doesn’t really tell the story. They rather tend to occupy a realm that certainly counts as genre fiction, but like so much contemporary science fiction, that aspect is more a matter of context and background than any motivating force for the story. In this case, the story takes place in the near future of a world in which Woodrow Wilson brokered a peace between Germany and Britain in 1915, ending the Great War and leaving the empires of the time largely intact. The problems in Grimwood’s stories have nothing to do with technology or its human consequences, and the form is quite deliberately that of the mystery/thriller. The Arabesks (Pashazade, Effendi, and Felaheen) include three semi-separate mysteries under the overarching story of Raf and his search for his own identity — he may or may not be the son of the Emir of Tunis, a man widely considered to be insane, who refused to sign the UN treaty banning genetic experimentation and so isolated his country from normal international intercourse. (This last becomes a key element in the larger mystery, although like so much of the story, it is decidedly understated.)

Identity is a central concern of Grimwood’s novels. He sees it as fluid, from the multiplicity of masks that everyone dons and doffs in daily life to the idea that, with the increasing velocity of the world — information flows faster, people move around more, verities are no longer sure — we don’t seem to have the same instinctual sense of who we are that our parents had. In the case of Raf, the ambiguity of others’ assumptions, his own memories — which are sometimes patchy — and verifiable information create a tension that is the real driving force behind the trilogy.

As does Bobby Zha in 9Tail Fox, Raf has an internal interlocutor, once again a fox. This one is a virtual fox that lives in his head and offers advice that is sometimes germane, often cryptic, and occasionally useful. Raf’s fox, however, is getting old; he wakes less and less, and his messages seem more and more tangential. These internal interlocutors seem to be another one of Grimwood’s standard devices, providing a nonstandard means of examining a character’s thoughts, one that adds to the momentum of the story rather than short-circuiting it, as is too often the case. Grimwood also makes adroit use of flashbacks to fill in back story, another instance in which he avoids the usual pitfalls: they become not only exposition but add another layer of ambiguity to the situation. Time becomes fluid as the mosaic of Raf’s identity and his history become more detailed

The net result of all this is a text that is subtle, indirect, and yet one that also moves along at a brisk enough pace to keep us engaged, and one in which a mix of genre tropes manage to fit together without awkwardness. I have to confess that on short acquaintance, I have come as close as I ever do to becoming a fan. Grimwood is that good.

(Spectra, 2007)