There’s a little bit of Watchmen in The American Way, in which a hidden conspiracy uses superheroes and manufactured threats to manipulate public opinion for the “greater good.” There’s a bit of Marvels, with a regular Joe type (in this case, a PR rep, as opposed to a newspaper reporter) commenting on and becoming part of the super-powered action. And there’s bits and pieces of Marvel’s Civil War, some Superman: The Movie, and a few others, all tied up in a historical package that’s honestly the most interesting part of the book.

There’s a little bit of Watchmen in The American Way, in which a hidden conspiracy uses superheroes and manufactured threats to manipulate public opinion for the “greater good.” There’s a bit of Marvels, with a regular Joe type (in this case, a PR rep, as opposed to a newspaper reporter) commenting on and becoming part of the super-powered action. And there’s bits and pieces of Marvel’s Civil War, some Superman: The Movie, and a few others, all tied up in a historical package that’s honestly the most interesting part of the book.

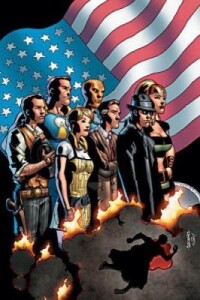

Originally published as an eight-issue limited series by Wildstorm, The American Way is set against the backdrop of an alternate Sixties, when a government program to create superheroes for propaganda purposes (the uninspiringly named Civil Defense Corps) starts hitting its first inevitable hiccups. Two pivotal events match our introduction to the world of The American Way: long-time uber-hero Old Glory drops dead of a coronary, and a bright young marketing exec gets brought into the super-powered Camelot to kick the program up to the next level. Ad man Wesley Catham, freshly on board, comes up with the idea of making the next member of the super-team an African-American, and from there, things rapidly get interesting. When The New American is revealed to be something other than lily-white, the team breaks down along regional lines, with most of the team’s Dixie contingent heading home and taking an increasingly aggressive stance. Meanwhile, a government-sponsored super-powered killer named Hellbent gets turned loose to provide a distraction – only to go off the rails, slaughter a bus full of civil rights activists, and take down one of the members of the CDC. And then things get ugly …

There are a lot of interesting pieces in The American Way, but they don’t all fit together smoothly. The central conceit of the book is that the heroes are literally made by the government for propaganda purposes, but then writer John Ridley throws a Norse goddess and a mysterious alien type into the mix, without rhyme or reason. The action is ultimately driven in large part by the super-powered serial killer Hellbent and his minions, but there’s no connecting tissue to show where those minions come from or why they find his semi-philosophy so appealing. It doesn’t help that Hellbent has the Dragonball Z power set of “whatever is needed at this given moment to move the plot along.” He ends up coming across as a plot device wrapped in the Joker’s hand-me-downs.

Ridley has done good work before — the script for the movie Three Kings, for example — but The American Way doesn’t quite hit the mark. Like many of the other post-modern superhero comics coming out these days (Top 10, Astro City, Ex Machina), The American Way uses the superhero metaphor as a lens for peering at a societal element from outside – in this case, the conflict between racism and the American spirit of inclusiveness. But in being a story about race, it stumbles over the superheroics, and when it’s a superhero comic, it falters in providing paper-thin villains who don’t do the subject matter justice. In the end, The American Way adds to the discussion on racism and comics when it could have been a definitive treatment. It’s interesting, but not compelling; worth a read but unlikely to join the discussion of truly heavyweight graphic novels.

(Wildstorm, 2002)