With its cumbersome title and dependence on vampire clichés, this paranormal romance offers very little in the way of original, engaging story. From a turgid and silly beginning, it improves toward the end, but once the last page is turned, nothing really has been gained. Nothing substantial has been contributed to the growing market for vampire romance novels. The only thing that potentially sets this novel apart from the horde of identical kiss-kiss-suck-suck stories is an attempt to reconcile and humanize a particularly vicious villain, but even that is only a subplot, and a flimsy one at that.

With its cumbersome title and dependence on vampire clichés, this paranormal romance offers very little in the way of original, engaging story. From a turgid and silly beginning, it improves toward the end, but once the last page is turned, nothing really has been gained. Nothing substantial has been contributed to the growing market for vampire romance novels. The only thing that potentially sets this novel apart from the horde of identical kiss-kiss-suck-suck stories is an attempt to reconcile and humanize a particularly vicious villain, but even that is only a subplot, and a flimsy one at that.

For protagonist Carrie Ames‚ trouble starts when a savagely mauled man admitted to the hospital where she works apparently dies. Upon visiting the morgue, Carrie discovers the man isn’t quite as dead or as human as she’d hoped: she is attacked by him and then recovers from the assault with some bizarre powers and cravings. Suppressing her scientific denials of her situation, she eventually realises she’s a vampire, and in seeking out a person who can help her with her condition meets Nathan.

Nathan’s a vampire who works for a shady organization called the Voluntary Vampire Extinction Movement. Like the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (an organization that actually exists, and which may or may not have served as Jennifer Armintrout’s inspiration), members are forbidden from siring new vampires and from hurting humans, but they are also prevented from offering life-saving medical attention to dying vampires, and feeding from involuntary hosts. Definitely unlike the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement, the vampire extinction is decidedly involuntary for vampires who are not members, and part of Nathan’s job is to track down and kill fledgling and rogue vampires while satisfying a number of romantic-hero clichés on the way. Sufficiently tragic past for brooding? Check. Fantastically sculpted bod? Check. Fatherly inclinations toward orphans? Check. European accent, in this case Scottish? Check and check.

Nathan is not so sexy once he gives Carrie an unappealing ultimatum: if she doesn’t join the Movement, he has to kill her. It’s inevitable, he believes, for a fledgling to become the same type of vampire as the one who sired her, and Carrie is unlucky enough to have been sired by one of the worst of the lot, a dastardly fellow by the name of Cyrus (go ahead and laugh at the name, even Carrie does). Carrie apparently has no choice; the act of siring a vampire creates a blood tie between sire and fledgling that is powerful and impossible to resist.

Carrie learns this information firsthand soon enough. When Nathan is poisoned by a witch in Cyrus’ employ, Carrie offers herself to her sire in return for the antidote. Cyrus is a rather pathetic figure. He’s incorrigibly evil; he not only keeps runaway slaves in his basement for feeding, but he’s also a pedophile, a rapist, and lives in a mansion with horrid Gothic décor. Aww, but he’s also desperately lonely, poor guy. Minutes after mangling a human in front of Carrie, he’s not averse to plaintively whimpering ‘Why don’t you love me’ right before slapping her around in a petulant rage.

The main plot focus of this book is on the twisted and just-this-side-of-believable love triangle between Carrie, Nathan (whom Carrie has genuine feelings for) and Cyrus, whose blood tie commands lust if not love from Carrie – although throughout the book she discovers that not all of her emotions for him can be blamed on the tie. It’s a freaky situation, although Jennifer Armintrout manages to pull it off, mainly through Carrie’s characterization. While she begins as one of those tired characters who feel the need to question everything instead of paying attention and learning as she goes, eventually she emerges as the most realistic character in the book, one whose witty comments and sarcastic remarks serve to lessen the overdramatic gothic element that is present in many modern vampire novels.

However, one good character is not enough to save a novel chock-full of wax figures masquerading as contributing players. Each character seems to have been given a list of rules at the beginning of the story, about how or how not to act, and as the story moves forward the action is so predictable the ending can be guessed several dozen pages in advance. Vampires have to suck, but novels don’t, so would taking a bit of creative license with the creatures in fiction be so terrible?

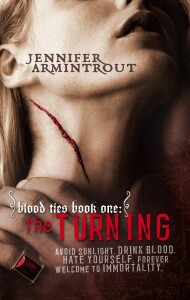

(MIRA, 2006)