The first thing one notices looking through the table of contents of The Poets’ Grimm is the overwhelming number of women contributors, a fact that editors Jeanne Marie Beaumont and Claudia Carlson acknowledge in their introduction. They allude to several reasons for this, one, of course, being the increasing number of woman poets of note, but more important, the fact that fairy tales and women seem to be inextricably bound: not only were the majority of the Grimm Brothers’ informants women, but women, most particularly in the Victorian Era when the Grimms published their collections, were the guardians of the “virtues of the hearth”: not only caretakers of the home, according to such eminent Victorian thinkers as John Ruskin, but the judges of the activities of men and the transmitters of culture — or, as we say these days, “values.”

The first thing one notices looking through the table of contents of The Poets’ Grimm is the overwhelming number of women contributors, a fact that editors Jeanne Marie Beaumont and Claudia Carlson acknowledge in their introduction. They allude to several reasons for this, one, of course, being the increasing number of woman poets of note, but more important, the fact that fairy tales and women seem to be inextricably bound: not only were the majority of the Grimm Brothers’ informants women, but women, most particularly in the Victorian Era when the Grimms published their collections, were the guardians of the “virtues of the hearth”: not only caretakers of the home, according to such eminent Victorian thinkers as John Ruskin, but the judges of the activities of men and the transmitters of culture — or, as we say these days, “values.”

Which is not to say that women, particularly woman poets, unthinkingly relay the status quo. Beginning in large part with Anne Sexton’s collection Transformations, women have not only investigated but reinvented the fairy and folk tale, bringing these timeless stories to bear on the most compelling and controversial issues of our time, as well as questions of personal identity and value. Thus we come across Emma Bull’s “The Stepsister’s Story,” a complex and ultimately searing tale told from the viewpoint of Cinderella’s stepsister, as much — or more — a victim of an unnamed “she” (the stepmother?) as Cinderella herself, who at least has made her escape.

There is a lot of subversion in this collection. The section “Variations and Updates” contains some pretty outrageous works, including Bruce Bennett’s “The True Story of Snow White,” in which the wicked queen has the dwarves shot and takes over the country. The section ends with Barabara Hambly’s take on Cinderella, “married a decade, three litters of neurasthenic/princes, your figure shot, not to mention your vagina.” That’s a natural lead-in to the following section, “Ever After, or A Few Years Later,” which includes Dorothy Barresi’s pungent comment, in “Cinderella and Lazarus, Part II”: “Forty years we’ve gone on dancing./The shoe’s on the other foot,/ but we are always exactly the same couple.”

The handsome prince is featured several times, another one of those archetypes that poets must deal with. In Gwen Straus’ passionately romantic “The Prince,” he is, as he says, “an old man in love.” “All my childhood,” he says, “I heard about love/but I thought only witches could grow it/in gardens behind walls too high to climb.” Randall Jarrell provides a prince’s version of waking Sleeping Beauty that becomes a vision of eternity: “For hundreds of thousands of year I have slept/Beside you, here in the last long world/That you had found; that I have kept.” Susan Mitchell gives us excerpts “From the Journals of the Frog Prince,” who, it seems, is not quite contented: “At her touch I long for wet leaves/the slap of water against rocks.”

There are stories told from the viewpoint of the wicked witch, the dwarves, the wolf, and a few contemporary characters, as in Tim Seibles’ “What Bugs Bunny Said to Red Riding Hood,” which includes an update on the fate of Goldilocks: “so last week the game warden nabs baby bear/passin out her fingers to his pals.”

The poets included are as diverse as the poems themselves: Anne Sexton, Neil Gaiman, Denise Levertov, Essex Hemphill, David Trinidad, Lucille Clifton, Kimiko Hahn, Denise Duhamel, Galway Kinnell are just a few of the better-known names. It’s a terrific collection — I was gratified by the consistently high quality of the works included, not to mention the range of viewpoints and treatments — that illustrates very well that fairy tales not only maintain their relevance, but continue to be wellsprings of inspiration.

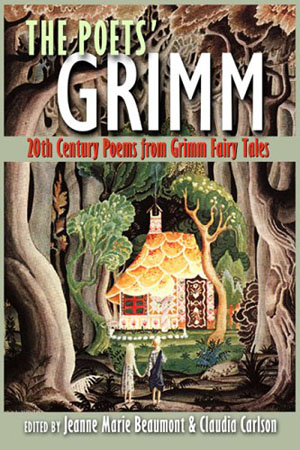

(Story Line Press, 2003)