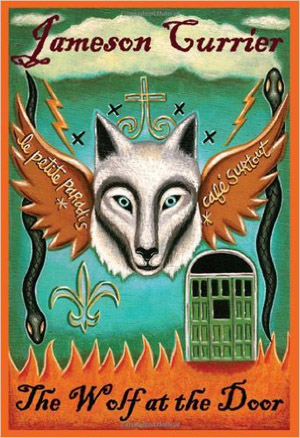

Start with a loose-around-the-edges guesthouse, Le Petit Paradis, in the French Quarter. Add a collection of gay men, co-owners, former owner, and staff, of various ages from toothsome twenties to frowzy forties. Mix in various combinations of lovers, ex-lovers, current boyfriends, potential partners (duration not guaranteed), tangled histories, and problematic futures. Top with a selection of ghosts. Sounds unbeatable, doesn’t it?

Start with a loose-around-the-edges guesthouse, Le Petit Paradis, in the French Quarter. Add a collection of gay men, co-owners, former owner, and staff, of various ages from toothsome twenties to frowzy forties. Mix in various combinations of lovers, ex-lovers, current boyfriends, potential partners (duration not guaranteed), tangled histories, and problematic futures. Top with a selection of ghosts. Sounds unbeatable, doesn’t it?

Avery Greene Dalyrymple III, the scion of generations of evangelists (well, two generations) and a non-believer, is one of the co-owners, the one who starts seeing ghosts. His ex, Parker, handles the cooking in the attached Café Surtout. Another ex, Mack, is the former owner who deeded the place to Avery and Parker in better days. He lives upstairs and is dying. Both Avery and Parker have new boyfriends, Avery’s being Hank, who works at the guesthouse, and Parker’s being Charlie Ray, an aging personal trainer. Avery’s relationship with Hank is on the rocks.

Avery discovers an antique knife buried under the pantry floor. And then he starts seeing ghosts, who turn out to be, by and large, those of the businessman who built the house in the 1820s, Antoine Dubuisson, his son Pierre, and their offspring and/or slaves. Avery also discovers an old diary that helps explain who’s who, and eventually comes across a manuscript left behind by Toby, Mack’s dead lover, which adds more history of the house and its early inhabitants.

And then Mack dies, which more or less brings things to a head.

I confess that when it came time to write this review, I was stumped. The book has received high praise, and I wondered if I weren’t missing something. I did something I almost never do: I read other reviews. They were uniformly glowing, tossing around such accolades as “erotic,” “witty,” “dramatic,” “funny,” etc., etc., etc., with abandon. Scratching my head, I looked at them again and came to a realization: not one of the reviewers offered a reason for their comments. (I try to be very careful about justifying my conclusions, on the assumption that there is an s.o.b. like me out there just waiting to nail me on something.)

Avery is the only character about whom we learn much, because he does all the talking. And boy, does he talk — pages and pages of description, history, speculation, rumination, sprinkled from time to time with a touch of self-deprecating humor, all of which led me to my first conclusion: he should just change his name to “Stereotype” and be done with it. Avery is a forty-something control freak who’s let himself go, drinks too much, gets excited by anything with the appropriate dangly bits, a nearly total airhead, and, one begins to think, not very bright. Everyone else, from Parker to Hank to Charlie Ray (who barely appears) to Buddy (“clean-cut, porn star quality waiter” — of course) to José (Latino and thus, by necessity, macho, and kitchen assistant to Parker), are largely props. Even Mack’s marginally homophobic sister, who could present a real threat to Parker and Avery and their respective businesses, is flat.

The onrush of verbiage from Avery tends to bury what should be the motivating events. I was nearly two hundred pages in, waiting for something to happen, when I realized that something had: Mack died. This was a crisis that would ultimately lead to a moment of — what? Transcendence? Realization? Redemption? Something? (It actually does happen, but the delivery is so uninflected, so mundane, and so lackadaisical that I wondered why anyone was bothering.)

The most real and most believable portions of the book are the old diaries that Avery discovers and reads. Those passages ride on dramatic tension, peopled by characters who take on reality as we watch them in action. Regrettably, they don’t translate into ghosthood very well, although we learn that Avery isn’t a completely self-centered nit as we see his compassion toward their plight. Regrettably, Currier didn’t manage to use that dramatic tension to effect in the larger story.

Oh, and about the wolf of the title: there is one, a psychopomp who appears to those about to die to lead them to the afterlife. Avery sees it more or less by accident — it’s come for Mack, as we learn — and doesn’t know what to make of it. As a symbol — and it could have been an effective one — it’s sort of half-baked.

And maybe that’s my problem with the book as a whole: it could have been a powerful and touching story. All the elements are there. They just never seem to connect with each other — there’s no resonance, no power, no engagement. I won’t draw comparisons, but I will note that there are books out there that take the middle-aged queen stereotype and turn it into an archetype, with all the wit, wisdom, pathos and bite that Currier missed.

– Robert M. Tilendis

Chelsea Station Editions, 2010