Rebecca Swain wrote this review.

Rebecca Swain wrote this review.

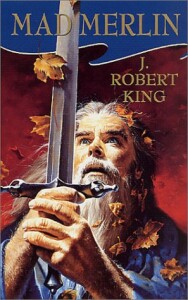

Fantasy writers have never forgiven the Christian god for supplanting all the pagan gods that came before him. To hear them tell it, the pagan gods weren’t too pleased about it, either. In J. Robert King’s first non-gaming novel Mad Merlin they actually see a way to prevent the Tetragrammaton, as they call Jehovah, from taking over. Young King Arthur proposes to build a city where all gods can live together as peacefully and tolerantly as the human population. The gods can help him build his Camelot, says Merlin.

But Merlin is mad. Well, he was mad. During the first half of this book he staggers around with crumbs in his beard and sauce on his chin, his only thought being how to acquire more food. At the end of the first section of the book he discovers who he really is (you won’t believe it!) and regains his sanity, although his madness then possesses Dagonet, a dwarf, and in the second half of the book the dwarf is the zany, unpredictable character the wizard was in the first half.

But I digress. Merlin is mad, so it’s hard to take his word about anything. He’s having this running battle with Loki, but since Merlin can’t separate dreams from reality, Loki may just be a dream. But Merlin dreamed Arthur, and Arthur is real, so …

Arthur and Merlin live Arthur’s childhood with Sir Ector and his family. When it is time for Arthur to take his place as king of Britannia, Merlin brings him Excalibur and its scabbard, Rhiannon, which will prevent the king from bleeding no matter how grievous a wound he sustains. (Guess what Excalibur really is!) But Arthur pulls the sword from the stone too soon, and has to go to war with Lot of Lothian on his coronation night. Lot steals Rhiannon, and then tries to gives it back, but Morgan won’t let him. Somehow Aelle the Saxon gets hold of the scabbard, and Arthur nearly dies at Mount Badon because he doesn’t have the scabbard. And Wotan really wants that god-killing sword.

And you already know Morgan Le Fey is plotting a way to get even with Arthur for what Uther did when he disguised himself as her father. And juxtaposed with bitter, evil Morgan is the beautiful Guinevere, who is really a fairy changeling. Only through her chastity can she preserve the healing power of the land, which Arthur needs to rule. But she and Arthur want each other so much it’s hard for her to remain chaste.

This book doesn’t tell the story past the battle of Mt. Badon, so we don’t see Lancelot or the great love triangle. Lot’s sons, Gawain, Gareth and the rest, don’t figure much here, either. They’re just knights of the round table, like dozens of others. Ulfius is the important character here, Uther’s chamberlain and later Arthur’s. “Why do I always get the rotten jobs?” he asks repeatedly. Jobs like trying to find Merlin in a crowd of beggars who all pretend to be Merlin, complete with magic powers. Jobs like rescuing the mad dwarf Dagonet from drowning in France, where Dagonet has proclaimed himself to be King Arthur, and Arthur’s allies believe him.

This is a wild, unusual telling of the Arthurian legend. The author plays with reality and illusion, and it is often as hard for the reader to tell the difference as it is for Merlin. Merlin’s madness; the presence of Loki, the trickster; Avalon, with its haven for forgotten gods; all tie into this theme of reality versus dream. In addition, we see the struggle of the old gods to survive the onslaught of the Tetragrammaton, and we see the human struggles as well, in the long, detailed battle scenes King writes. This is a violent book, although King isn’t as graphic as he could be.

I enjoyed this book very much. I have read numerous retellings of the Arthurian legend, but this one was different enough to keep my interest. It is humorous and full of adventure, and I highly recommend it to readers who still can’t bring themselves to admit that Arthur and Merlin are gone.

(Tor, 2000)