The Silmarillion is often described as a difficult book. This is partly because its first readers went to it with the expectation that it would be an adventure story similar to J.R.R. Tolkien’s other works and were totally confused by its complete abandonment of the conventions of the novel. Instead of a fast-paced, hair raising, tightly focused plot, one gets long lists of unpronounceable names, while Tolkien’s high-flown, archaic language and the lack of a focus character create an “alienation effect.”

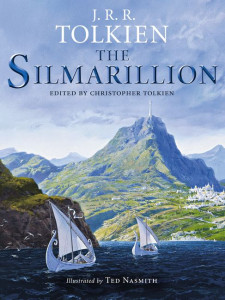

Over 60 years in the making, The Silmarillion is the work that Tolkien hoped would be his crowning achievement. Unlike The Hobbit or The Lord of The Rings, The Silmarillion is not a novel, but a compendium of the mythology of the Elves.

Compendium is the operative word here. The Silmarillion was assembled by Christopher Tolkien after his father’s death from a 60-year accumulation of unorganized manuscripts and notes. Christopher tried to consolidate myriad often conflicting versions into a single narrative, “selecting and arranging to produce the most coherent and internally self-consistent narrative.” While Christopher Tolkien bemoans the occasional unavoidable incompatibilities of style that are found throughout the book, they do help to convey the impression that J.R.R. Tolkien sought to create — the feel of a book that was compiled over long ages by several different authors who didn’t always understand or agree with one another.

Christopher Tolkien’s work was also made more difficult by the fact that his father’s prodigious imagination appeared to have gone totally out of control in the composition of The Silmarillion. Tolkien’s ability to envision a world down to its last leaf and petal made it impossible for him to finish the work. His tendency to rewrite and revise the book was intensified by his need to reconcile the narrative in The Silmarillion with that of The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings. Characters that are central to the Middle-earth of those books, such as the hobbits and Galadriel, weren’t originally mentioned in The Silmarillion. The world and the narrative just kept growing larger and larger.

Like all mythologies, The Silmarillion gives, among other things, an account of how the universe was created, why evil exists, and the ultimate fate of the universe. It also provides the backstory for Tolkien’s tales of Middle-earth. Though Tolkien’s mythology draws heavily from Nordic and Judeo-Christian sources, he adds his own ideas to the mix so that The Silmarillion is more than just Mythology 101 reheated.

The Silmarillion consists of five sections:

- Ainulindalë (the Music of the Ainur; a creation myth)

- Valaquenta (Account of the Valar; a roster of the Gods)

- The Quenta Silmarillion (the history of the Silmarils)

- Akallabêth (the Downfall of Númenor)

- The Rings of Power and the Third Age

It also contains an annotated Index of Names and an Appendix: “Elements in Quenya and Sindarin Names.”

The story begins when Ilúvatar/Eru (whose name suggests the Norse “Allfather”) brings into being angel-like entities called the Ainur who are “the offspring of his thought.” When the universe is still a void, Ilúvatar calls the Ainur together and asks them to improvise on a musical theme that he has composed. This choral composition serves as the blueprint for the universe. One of the Ainur, the Lucifer-like Melkor, leads a rebellion against Ilúvatar. The Silmarillion tells of the battle between the deities and how it spread to the races that came to populate Middle-Earth.

Tolkien’s Ilúvatar/Eru is defined not so much by his power, but by his creativity. He creates the Great Music of the universe. His only remark on Melkor’s rebellion is to say that Melkor unknowingly is promoting his grand design: that Melkor’s introduction of dissonance into the musical mix will create a deeper, more beautiful resolution when the final Music is performed. This will be on Judgment Day. Ilúvatar is not a vengeful god, so rather than being a day of trials and retribution, Judgment Day will be a great reconciliation that will feature another group sing “by the choirs of Ainur and the Children of Ilúvatar” where everyone will hear the music and “all shall understand fully his intent in their part, and each shall know the comprehension of each.”

While the Greek mythology and Christian teaching made pride the usual reason for a fall, the two greatest “falls” in The Silmarillion are brought about by creative frustration. Melkor, the first Dark Lord, was fascinated by the primal void and took to hanging out alone in it and imagining what he would create out of it if he had Ilúvatar’s ability to create life. When the planning of the universe finally takes place as a choral performance, Melkor tries to put his stamp on creation by inventing dissonance. Ilúvatar, however, creates two new themes that bring Melkor’s part back into harmony and the “Children of Ilúvatar,” (Elves and Men) are created in the third theme. Melkor is angered at having his part overwritten and partially submerged in the composition. Later, he looks over creation and discovers that it is nothing like what he would have done and he starts to sabotage the work of the other Ainur who are making the vision revealed in the “Great Music” a reality. Still later, the Elven craftsman Fëanor’s anger at losing his masterworks, the Silmarils — three priceless jewels that contain a sacred light — leads to the exile of the Elves and plunges Middle-Earth into an endless cycle of wars.

So why read The Silmarillion if it is difficult? The obvious answer, “because it is the backstory to The Lord of the Rings,” doesn’t do the book justice. The Silmarillion is way more than just a prequel. It can stand on its own as a work of art. The first test of a mythology, invented or otherwise, is that it does a satisfactory job of explaining the world in striking, unforgettable language and images. The universe Tolkien creates in the book haunts its readers and makes them see this world in a new light. Scattered through the lists of names are passages of rare beauty. Tolkien began his writing career as a poet and the “alienation effect” I mentioned earlier brings his words to the forefront of The Silmarillion. The book abounds with striking descriptions — primal darkness giving way to primal light, liquid light condensing as an iridescent dew on the leaves of the gold and silver trees of Valinor, music like “a raging storm of dark waters.” Poetic devices such as rhythm, alliteration, and repetition are used to hypnotize readers. Finally, Tolkien’s minute descriptions of the world of Middle-earth make it seem larger than life and twice as real as our own earth. It’s a rare reader who can put down The Silmarillion without feeling bereft in the knowledge that the Shangri La of Middle-earth is forever out of reach.

(Houghton Mifflin, 1977)