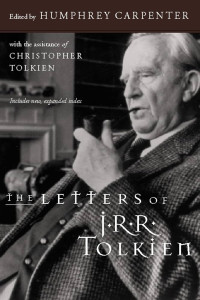

Not surprisingly, the Green Man library contains many items related to J. R. R. Tolkien and his works. Tolkien is one of the best creators of fantasy who ever lived, period. And the recent films based on The Lord of The Rings have caused a resurgence of interest in him and his works. No doubt have I that you’ve read both The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings, as you wouldn’t be reading this review if you hadn’t, but have you ever encountered the man who wrote those works? Well, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien will give you a look at Tolkien himself in ways that are both charming and perhaps surprising.

Not surprisingly, the Green Man library contains many items related to J. R. R. Tolkien and his works. Tolkien is one of the best creators of fantasy who ever lived, period. And the recent films based on The Lord of The Rings have caused a resurgence of interest in him and his works. No doubt have I that you’ve read both The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings, as you wouldn’t be reading this review if you hadn’t, but have you ever encountered the man who wrote those works? Well, The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien will give you a look at Tolkien himself in ways that are both charming and perhaps surprising.

Tolkien lived in that long-vanished era when letter writing was an intrinsic part of daily social and business activity. There were few phones, obviously no e-mail, and telegrams were used only for very urgent business. (He did use airgraphs, a special postal service to reduce the mail volume, for letters to Christopher and the like.) But the proper gentleman or gentlewoman wrote letters — lots of letters! And Tolkien was, like the hobbits he created, a perfect English gentleman. (Hobbits? English? Of course! Certainly as English as the characters in Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in The Willows. Perhaps even more English than the English themselves, as they are an idealized version of the English gentleman.) Do you remember my criticism of Seamus Heaney’s Beowulf for attempting to make literate that which is truly oral? Tolkien is quite the opposite — his work is intended to be read, not heard. And his letters are definitely literary affairs worth savouring.

‘…If you wanted to go on from the end of The Hobbit I think the ring would be your inevitable choice as the link. If then you wanted a large tale, the Ring would at once acquire a capital letter; and the Dark Lord would immediately appear. As he did, unasked, on the hearth at Bag End as soon as I came to that point. So the essential Quest started at once. But I met a lot of things along the way that astonished me. Tom Bombadil I knew already; but I had never been to Bree. Strider sitting in the corner of the inn was a shock, and I had no more idea who he was than Frodo did. The Mines of Moria had been a mere name; and of Lothlorien no word had reached my mortal ears till I came there.’ — J.R.R. Tolkien to W.H. Auden, June 7, 1955

I have a few caveats that I’ll mention, but let me strongly note that The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien are a must-read for Tolkien scholars and anyone interested in finding out, firsthand, the comments, internal ramblings, and thoughts of Tolkien in regards to his own works and his beliefs on a variety of topics — including what The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings meant to him. Possibly. Maybe. One site states that this volume was, ‘[c]ompiled and edited by Tolkien’s biographer (and equipped with an impressive index, and a brief blurb at the beginning of every letter to explain the background of the letter, and identify its recipient)….’ Well, there are some things missing here; Humphrey Carpenter, author of Tolkien: A Biography, notes that no correspondence exists between 1913 and 1918 to his future wife, Edith Bratt. Eh? Carpenter gives no explanation for this, nor does he anywhere explain what happened to almost all of the correspondence Tolkien conducted from 1918 to 1937! That’s a very long time for correspondence to have gone astray. Since Carpenter notes that, ‘Between 1918 and 1937 few letters survive, and such as have been preserved record (unfortunately) nothing about Tolkien’s work on The Silmarillion and The Hobbit, which he was writing at this time. But from 1937 onwards, there is an unbroken series of letters to the end of his life, giving, often in great detail, an account of the writing of The Lord of The Rings, and of later work on The Silmarillion, and often including lengthy discussions of the meaning of his writing…’ it would certainly seem that he could have explained why there is no record now of correspondence for the missing period.

So, what do you get here? Oh, lots of interesting notes, such as what were Tolkien’s initial efforts in getting The Lord of The Rings and The Silmarillion published, and why did Collins, an English publisher, refuse to publish The Lord of The Rings or The Silmarillion. You get his pithy commentary on what he thought of fanfic (slang for fan fiction) as extensions of his own work. Answer: not very much; he called one such person ‘a young ass’ and his work ‘tripe.’ Mind you, it was likely shite, so he was most likely justified in his comments. Needless to say, these fans were not happy with his attitude, even though it is a standard one among writers to this day.

Letter #131 in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (written in 1951 and running over ten thousand words in length!) is particularly worthy of commentary. When Allen & Unwin declined to publish The Silmarillion and The Lord of The Rings, Tolkien hoped that Milton Waldman of Collins would publish both books. He wrote a very long letter to Waldman demonstrating why the The Lord of The Rings and The Silmarillion must not separated (in me opinion, The Silmarillion sucks as fiction). In the book, in a slightly abridged form, the letter runs for 18 pages. It should be required reading for every serious Tolkien fan with serious questions about his mythopoeic undertaking. It’s obvious, painfully obvious, that Tolkien thought as much of The Silmarillion as he did The Lord of The Rings.

I could go on at length noting interesting things herein, but I’ll let you, my dear reader, discover the joys of this collection. And yes Virginia, there was a real Sam Gamgee. Just see letter #184 for the correspondence between him and Tolkien. No, Tolkien did not base his Sam Gamgee on him! The only noticeable difference between the earlier hardcover printing of this book and the current trade paper printing is a new and somewhat longer introduction. Personally, I’d get the hardcover, as it’s much more durable than the paper-bound version.

(Houghton Mifflin, 1981; reprinted in softcover, 2000)