Liz Milner wrote this review.

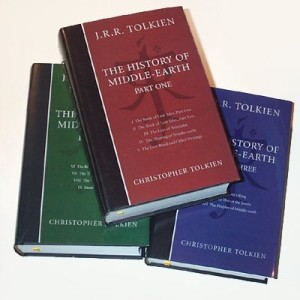

The History of Middle-Earth offers an unprecedented opportunity to examine a great writer’s creative development over a period of 60 years. At his death, J.R.R. Tolkien left a huge body of unfinished and often unorganized writings on the mythology and history of Middle-earth. In The History of Middle Earth (HoME), his son, Christopher, has sought to organize this huge collection of drafts, revisions and reworkings into an organized and intelligible whole. The series was originally issued by Houghton Mifflin in twelve volumes. In January of this year, HarperCollins consolidated the twelve volumes into a hefty three-volume hard cover set, which to my knowledge has only been released in England (editor’s note: it is now available as a five-volume mass-market paperback set). Details can be found on HarperCollins’ English Web site. Since a review of all twelve volumes threatens to be almost as long as one of Tolkien’s books, I have divided this review into three parts. Part One of the review deals with Volumes I-V of HoME (Book I of the new HarperCollins set).

The Book of Lost Tales, Vols. I & II (written 1916-1917)

The Book of Lost Tales forms the first two volumes of The History of Middle Earth. It was written in the years 1916-17 by the 25-year-old Tolkien, while he was serving as a signal officer in World War I. It is Tolkien’s earliest written description of the land he would later call Middle-earth and is the first draft of what later became The Silmarillion.

Volume I deals with the creation of the universe, the rebellion of the angel Melko, the creation of the sun and moon, and the origin of elves, men and other creatures. The second volume deals with the early history of Middle-earth, and in particular, the stories of Eärendel and Elrond’s ancestors. It consists of the stories of “Beren and Luthien,” “Túrin and the Dragon,” “The Necklace of the Dwarfs” and “The Fall of Gondolin.” Each tale is followed by commentary in the form of a short essay plus information on names and vocabulary.

In The Book of Lost Tales, the history of the Elves is told by using the device of an inquisitive human traveller, Elf wanna-be Eriol, who journeys to Tol Eressëa, the “Lonely Isle” of the Elves. While enjoying Elvish hospitality, Eriol (also called Eriel or Aelfwine) hears their stories of ancient times. Eriol serves as more than a framing device, for he links the world of Middle-earth to early English history and legend. Eriol is initially described as being a kinsman of Hengest and Horsa, the leaders of the first Germanic invasion of Britain and the founders of the Kingdom of Kent. Eriol, unfortunately, is never realized as a character. He is a plot device for getting his hosts to tell the story of their origins.

The Book of Lost Tales presents the earliest form of Tolkien’s mythology in a linguistic form I think of as “Ye Olde Speake.” You know — peppering sentences with archaic words and inverting the order of nouns and verbs to give an artificial sense of age and grandeur (or is it grandiosity?). In addition to creating an air of artificiality and distance, the use of Ye Olde Speake also creates narrative flatness. It’s like writing only in capital letters. When everything is written in sublime, high-fantastical style, there’s no language available to express greater degrees of wonder, fear and excitement. Anyway, one or two “How came thee hithers” is enough to set my teeth on edge and spoil my morning. To make it all more daunting,The Book of Lost Tales is two volumes of Ye Olde Speake without a single hobbit to lighten things up. (To be fair, Tolkien, who was one of the world’s greatest scholars in Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse, came as close as anyone has come to approximating Old English style in Modern English. It may be Ye Olde Speake, but at least it’s the genuine article).

Pacing is also a problem. I’d always thought the pace of The Silmarillion was slow. After reading The Book of Lost Tales, The Silmarillion seems to race along with MTV-like speed. In The Book of Lost Tales, for example, it takes thirty pages to get the sun and moon into operation, while it only takes five in The Silmarillion.

Despite my initial resistance to the language and pacing, I did find myself being drawn into the storyline. I felt a certain frisson on reading that Eriol means “one who dreams alone.” It was the first hint of the sad beauty that infuses Middle-earth. Tolkien’s depiction of Elvish hospitality has great charm and three dimensionality, perhaps because he was drawing on imagery that is firmly rooted in British ballads and folklore. Anyway, his description had me wanting to join the party. (At this stage in the mythology, by the way, Tolkien’s elves are pint-sized and the man, Eriol, has to be magically shrunk to join in their revels.)

While the Judeo-Christian God (Yahweh) created the world with a word, Tolkien’s God Eru or Iluvatar creates it with music. And while Yahweh’s creation was a solitary one, Iluvatar collaborates with his angels, the Ainur, in a choral piece for heavenly voices that not only brings all things into being, but also fixes almost the entire fate of the universe. (Tolkien later altered the story so that the choral performance is only the blueprint; creation is only finalized when Iluvatar speaks a word of power.) Evil comes into the world when the disgruntled angel Melkor/Melko/Morgoth (a closet Wagnerian) invents dissonance to show his originality. While pride was to blame for Lucifer’s fall, Melkor’s is due to a mixture of pride and frustrated creativity. Iluvatar reserves the making of living beings as his exclusive prerogative, and Melkor looks out on the unpopulated world and longs to create “children” of his own.

Tolkien’s early drafts of The Book of Lost Tales should serve as inspiration to all fledgling fantasy writers, because parts of it are so silly that it’s hard to believe Tolkien could have had a hand in it. In The Silmarillion, for example, Luthien outwits Morgoth’s servant Sauron to free Beren. In The Book of Lost Tales, she outwits a very large, clueless, talking pussycat. She is aided in this by a very large, somewhat taciturn, talking hound. The introduction of the cat and dog subplot combines epic with Sunday cartoon elements in a way that’s ludicrous.

The second volume of The Book of Lost Tales chronicles the histories of several of Elrond’s ancestors. Túrin, the hero of “Turambar and the Foalóke,” is several unlucky heroes rolled into one. Though he has the strength and courage of a super hero, he has been cursed by Morgoth. Because of the curse, he is a Jonah — everyone he tries to help is annihilated. He has a dysfunctional family to rival Oedipus (only Túrin sleeps with his sister, not his mother), and, like Beowulf, he slays a dragon and the treasure his people gain from its horde is tainted and assures their destruction.

Túrin and all the human and elvish characters in the story seem limp and clueless. The only characters with energy and vision are Glorund, the dragon, and Gurtholfin, “Wand of Death,” the bloodthirsty sword. Túrin is Fate’s most hapless schlemazel. He doesn’t grow, he just absorbs blow after blow like an inflatable punching doll. He also has no introspection. He possesses a magic talking sword, Gurtholfin, that loves to drink blood. Whether the blood belongs to friends or foes of Túrin is of absolutely no importance to the sword. One would think that after slicing and dicing a few loved ones, Túrin might consider getting rid of the magic sword, but it doesn’t seem to occur to him.

With the exception of Luthien and Beren, all of the heroes in The Book of Lost Tales, Vol. II are lone wolves who are defined solely by their prowess in battle. This is a tremendous contrast to Tolkien’s later work in The Hobbit and The Lord Of The Rings, where Bilbo and Frodo are depicted as part of a cooperative effort. They are also the products of a society that values community ties over individual achievement. Moreover, hobbit society seems to be held together by a vast network of ritual exchanges and obligations, as embodied in the hobbits’ complex birthday customs. Bilbo, Frodo, and the other characters also share a vast cultural inheritance, and their mastery of ancient lore is an essential and often demonstrated part of their personas. In The Book of Lost Tales, however, Tuor, the hero of “The Fall of Gondolin” and father of Eärendel, is described as a master of lore and music, but we have to take this on faith, because he is too busy hewing and hacking to demonstrate any other abilities.

The Lays of Beleriand, Volume III

In a defense of Tolkien’s poetry, (“The Poetry of Fantasy: Verse in The Lord of the Rings,” in Tolkien and the Critics, Neil D. Isaacs and Rose A. Zimbardo, eds., University of Notre Dame Press, 1968, pp. 170-200), Mary Quella Kelly admits that many readers find Tolkien’s verse “insufferable,” and in the article “Tolkien’s Hobbling Habit” Chris Mooney writes, “The Lord of the Rings is… full of poetry that is… simply awful.” Therefore, the prospect of reading The Lays of Beleriand, Vol. III of The History of Middle-earth, a whole book of nothing but Tolkien’s poems with commentary by his son Christopher, is enough to fill many readers’ hearts with dread. Tolkien’s poetry, at its worst, can be sing-songy and soporific with far too many pallid elf maidens wafting around for my taste. I would gladly trade a thousand Niphrondels for a single stark, gory border ballad. So I approached this book with trepidation, but I found it a whole lot more interesting than I’d expected. In this volume, Tolkien gets out of Ye High Olde Groove, and while the language isn’t exactly contemporary, it is a whole lot more vivid than anything in The Book of Lost Tales.

The Lays of Beleriand contains two poems, the alliterative “The Lay of the Children of Húrin” and “The Lay of Leithian” (in octosyllabic couplets). The book concludes with a Commentary on “The Lay of Leithian” by C.S. Lewis.

“The Lay of the Children of Húrin” is an alliterative verse version of the story of Túrin. Tolkien’s alliterative verse uses archaic word order that sometimes makes the action hard to follow; you don’t always know who the agent and the object are because the usual word order is reversed.

“Ground and grumbled on its great hinges

the door gigantic; with din ponderous

it clanged and closed like a clap of thunder,

and echoes awful in empty corridors

there ran and rumbled under roofs unseen….”

Alliterative verse, however, forced Tolkien to write with greater vividness and economy. It is also less sing-songy than the poetry we usually associate with Tolkien. Occasionally Tolkien achieves some powerful effects, as in his description of the death of the oath-breaker Blodrin who is struck in the throat by an orc arrow and impaled to a tree.

“He bargained the blood of his brothers for gold…

By an orc-arrow his oath came home.”

A reading of The History of Middle-earth makes it clear that Tolkien’s poetry was an integral part of his creative process. Tolkien did not, as I first imagined, write the prose versions of the mythology first and then put them into verse. Instead, the prose and poetic versions evolved together. He would shift from one to the other depending on the mood he was in, and much of the mythology was developed and refined in the verse versions of the stories.

Tolkien used poetic devices throughout his work. When I heard Rob Ingles’ recording of The Lord of the Rings, I was struck by how much of Tolkien’s prose has a luminous quality, a haunting resonance created by his use of alliteration, assonance, and rhythm. These patterning tricks have been used in ballads and sagas for millennia to fix words firmly in the mind. Tolkien’s use of these poetic devices in his prose helped create the otherworldly atmosphere of Middle-earth. In The Two Towers, for example, Tolkien writes of “melting icicles of moonlight,” that illuminate Gollum “just beyond the boil and bubble of the fall, cleaving the black water as neatly as an arrow….” (Book IV, Chapter VI, “The Forbidden Pool.”) Tolkien’s poetry may not have been first rate, but it informed his prose and sometimes made it sing.

Tolkien’s use of poetry in The Lord of the Rings also highlights the interconnectedness of the cultures of Middle-earth. Frodo, Aragorn and the other members of the Fellowship are able to create poetry extemporaneously because they are all products of a culture that provides them with the rules and framework for creation and performance. (I was amused by Kelly’s throwaway comment that these characters’ ability to compose poetry extemporaneously was intended to drive home the strangeness of Middle-earth and the fact that the story is not about people like us. How I long to take her to a session in Plockton, Scotland, where people compose extemporaneous songs in both English and Gaelic!)

The octosyllabic “Lay of Leithian” is yet another retelling of the story of Luthien and Beren. Its greatest interest lies in its description of Thu, Morgoth’s evil sidekick, who later turns up in The Hobbit as “The Necromancer” and in The Lord of the Rings under the name of Sauron.

The Shaping of Middle-earth, Volume IV

Volume IV, which includes “The Shaping of Middle-earth,” “The Quenta,” “The Ambarkanta,” and the “Annals,” is most useful as a reference text for hard-core Middle-earth addicts. This book gives a huge amount of background information on the chronological and geographical structure of Tolkien’s invented world. The “Ambarkanta,” or “shape of the world,” presents a description of the geography of Middle-earth before and after the War of the Gods and the Downfall of Númenor, when the Gods reshaped the flat earth and made it round. It also includes maps that are the earliest graphic depictions of Tolkien’s alternate universe.

In the “Annals of Valinor” and the “Annals of Beleriand,” the chronology of the First Age is developed. These are written both in modern English and in an Old English version that purports to be the translations made by Eriol (a.k.a. “Aelfwine”), the English wanderer and elf wanna-be who appeared at the beginning of The Book of Lost Tales, and who was originally intended to link the history of England with that of Middle-earth.

The “Quenta Noldorinwa” of 1930 is the only version of The Silmarillion that Tolkien completed. This work was interrupted by the writing of The Lord of the Rings, and when he returned to the manuscript after The Lord of the Rings was published, he found that The Lord of the Rings did not agree in parts with the “Quenta Noldorinwa.” To make his mythology consistent with his published work, Tolkien embarked on another revision, which, much like Niggle’s leaf, grew in complexity until its author was completely lost in it. Also included in this volume is “The Sketch of the Mythology” (1926), which is an early version of The Silmarillion. It was composed in 1926-30 to explain the background of the alliterative version of the story of Túrin and the Dragon (“The Lay of the Children of Húrin”).

The Lost Road and Other Writings, Volume V

Volume V, The Lost Road and Other Writings: Language and Legend before the Lord of the Rings, includes Tolkien’s writings on the First Age up to 1937, early drafts of the Legend of the Fall of Númenor, and the beginnings of a novel, The Lost Road, an abandoned time travel story. The Lost Road attempts to connect our history with that of Middle-earth by providing links between European legends (Beowulf, Atlantis and the Irish tales of Tir-nan-og) with incidents in the history of Middle-earth. A 20th century English father and son, who are the unknowing descendents of Elendil, develop the ability to reexperience their past lives and live the history of Europe and Middle-earth backwards until they experience the fall of Númenor/Atlantis.

Also included in this volume are an account of Valinor and Middle-earth before The Lord of the Rings, which consists of:

• The annals of Valinor and Beleriand,

• the Ainulindalë or the Music of the Ainur and the creation of the world

• the Lhammas or Account of Tongues, a history of the elvish languages

• the Etymologies, a lexicon that provides historical explanations of elvish vocabulary

The final section of the book (that is, Volume I in the new HarperCollins edition) contains an appendix, genealogies, a list of names, and a second Silmarillion map.

Each volume of the three-volume set contains a frontispiece and is illustrated with maps, photographs of Tolkien’s elaborate calligraphy manuscripts, and working drawings. These are rather sparsely distributed throughout the series. I would have welcomed more illustrations, since Tolkien, who was an excellent amateur artist, used his drawings and paintings as another way of bringing his imagined world into sharper focus.

Why read this compendium of first drafts, false starts and abandoned plot lines? Tolkien’s drafts and notes give greater insight into the story “behind the story.” While most writers “give the readers what they want,” Tolkien was a master of withholding it. His Middle-earth is full of tantalizing glimpses of a history and a whole universe beyond his novels, a vast world with little breadcrumb trails of story that branch off from the main plot, together with massive appendices that give teasing bare-bones outlines of a rich body of lore. The History of Middle-earth fleshes out this world. It also charts Tolkien’s development as a writer. Finally, and most importantly, this series provides more evidence that Tolkien had one of the most strange and wonderful imaginations that ever was. Even in his earliest, clunkiest writings, his infinite inventiveness shines forth. A person who could imagine a world created by a choral performance, where light was a liquid (just imagine what a blizzard of light would look like!), and where death is the most precious gift of a loving God may be many things, but humdrum is not one of them.

A note on the new HarperCollins edition: as I mentioned earlier, HarperCollins has consolidated the original twelve volumes into a three-volume hardcover set. Each volume of the set is £50. I initially had trepidation about the set. Each book is very large (Volume I is over 1200 pages, and the set takes up about seven inches of shelf space — this is not a book you can tote around in your purse). The paper it is printed on seems insubstantial, slightly thicker than onionskin. Volume II, however, passed the endurance test when the book and I were the victims of a sneak attack by a large, affectionate and very wet setter. I also managed carry Volume III through a long airplane trip without developing a hernia. Best of all, toting around this huge moose of book gave me instant credibility at Mythcon.

Part II: The History of the Lord of the Rings

Reading The History of the Lord of the Rings has convinced me that divine providence must exist. It’s the only way to explain J.R.R. Tolkien’s 180-degree shift from writing a jokey story about the adventures of jolly hobbit’s hobbit Bingo Baggins, son of Bilbo, to The Lord of the Rings (LotR) and its melancholy hero, Frodo.

The History of LotR was originally issued in separate volumes by Houghton Mifflin, and recently has been consolidated and released by HarperCollins as Part II of the three-volume History of Middle-earth (HoMe) set. The contents of The History of LotR are as follows:

• Volume VI: The Return of the Shadow

• Volume VII: The Treason of Isengard

• Volume VIII: The War of the Ring

• Volume IX: Sauron Defeated

The first volume in The History of LotR (or Volume VI in HoMe) is entitled The Return of the Shadow (1937-1939). It covers the period from the creation of the story up to the Mines of Moria and explains the three major rewrites of the story Tolkien did during this period. There are seven illustrations, mainly maps and manuscript pages that depict the story from the Shire to Moria.

In an earlier issue of Greenman, Jack Merry described Christopher Tolkien’s editorial work on the history of Middle-earth as “a task worthy of Telemachus.” In his editing of The History of LotR Christopher Tolkien adds the endurance and cleaning power of Heracules to the mix. J.R.R. Tolkien saved everything he wrote in his 60-year writing career, but he never got around to organizing his papers. Due to his characteristic disorganization, part of the manuscript of LotR was sold to Marquette University in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, while the earliest versions of LotR were forgotten among the papers that Christopher Tolkien inherited at his father’s death. The manuscript wasn’t only disorganized; it was virtually illegible, because Tolkien often wrote in ink over earlier pencilled drafts. Christopher Tolkien describes the quality of the manuscript as “appallingly difficult to decipher, a fearsome scrawl… beyond the limits of legibility… practically a code… so that one must try to puzzle out not merely what my father did write, but what he intended.” Christopher Tolkien is probably the only person on earth capable of making sense of this “chaotic wreck,” because he served as his father’s typist, mapmaker and sounding board during the writing of the book and therefore is in a unique position to give the inside story on the writing of LotR.

Christopher Tolkien prints the earliest form of each chapter of LotR in its entirety, provides a commentary, summarizes later changes and compares these with the final form found in the published LotR. A smattering of early maps and drawings are included. In his commentary, he lovingly chronicles his father’s strike-outs, revisions, and illegible pencil scrawls. He also points out spots in the manuscript where the handwriting betrays the author’s excitement. It’s almost like peeping over Tolkien’s shoulder as he wrote. It led me to wonder whether, in a computer age, the opportunity to do an analysis of this sort will be totally lost, or whether the computer geeks of the future will use forensic techniques on the hard drives of famous authors to reveal where Stephen King’s keystrokes faltered or accelerated or when Danielle Steel changed normal font to italic.

When Tolkien began his sequel to The Hobbit, he hadn’t a clue to what the new book would be about, only that it would concern Shire hobbits and a quest to get rid of Bilbo’s magic ring. Since Tolkien had written that Bilbo had lived happily ever after the adventures described in The Hobbit, he felt the new story would require a new protagonist whose fate would be uncertain.

Reading Tolkien’s early chapters is dizzying because the plot is light years away from LotR, but a great deal of the dialog from those early drafts made the final cut (though many of the characters who first voiced it do not). The famous “Long-Expected Party,” for instance, begins as a rather low-key affair. In the earliest draft of the Party scene, Bilbo simply announces he’s leaving the Shire to get married. There is no fireworks display and no disappearance. In a later draft, Bilbo doesn’t hold the party at all. Instead, he and his wife, Primula Took, go off on a long journey and never return. Their son, Bingo, the original protagonist of LotR, holds the “Long-Expected Party” and utters the speech that we now associate with Bilbo.

Bingo is depicted as a “type A” hobbit, a macho munchkin who is excessively smug and inordinately fond of the gold buttons on his vest. His madcap humor and love of practical jokes would have mortified the ever-polite Frodo Baggins. Bingo’s behavior is often way over the top. His quarrel with Farmer Maggot originates when, as a youngster, he not only steals the farmer’s mushrooms but also kills one of his beloved dogs. The farmer beats young Bingo, but adult Bingo uses the ring to get even. He makes himself invisible and knocks Maggot down and trashes his home. This is light-years away from Frodo’s embarrassment over his childhood misdemeanors. Bingo’s exploits also make it clear that he was not the sort to have pity on Gollum.

Tolkien’s publisher had requested a lighthearted sequel to The Hobbit. Tolkien strove to comply, but the lighthearted story took an “unpremeditated turn” when a menacing horseman shrouded in black rode into the action demanding to know the whereabouts of “Baggins.” The Black Rider didn’t seem like a suitable character for a story for young children, but Tolkien couldn’t keep him out, and soon the rider returned bringing his buddies.

Black Riders weren’t the only problem Tolkien had to deal with. After a long period of being stuck because he couldn’t decide what the story was about, the story suddenly began to write itself and Tolkien appears to have a hard time keeping up with it.

In The History of LotR, Tolkien is constantly dealing with a protean, ever-expanding universe. Middle-earth seemed to be shaping itself as Tolkien wrote of it, and this caused him problems of chronology and geography. For example, a journey that takes the Dwarves one hour to complete in The Hobbit takes the ranger Trotter/Strider/Aragorn and the hobbits six days because the terrain has changed so much. Another example is Sauron’s kingdom. Tolkien began writing with the intention of having the quest end at Sauron’s (a.k.a., the Neuromancer’s) headquarters in Mirkwood, a mere hop, skip and a jump from Rivendell. When a character off-handedly mentioned that the White Council had successfully driven Sauron out of Mirkwood and back to Mordor, his ancient fortress in the South East, Tolkien had to invent a geography and a backstory for Mordor and the lands that separated it from Rivendell.

The geography of Middle-earth wasn’t the only aspect of the story that constantly changed. The personalities of the hobbits seemed as changeable as the land they traversed. In the earliest versions of LotR, Bingo’s relationship to the other hobbits was that of an indulgent uncle showing his young nephews the world. He sets out on his journey in the company of Marmaduke (later Meriadoc) Brandybuck, and Frodo, Odo and Drogo Took. Tolkien soon found that he had more hobbits than he could handle —- and Tooks at that. Drogo quietly vanished. Meriadoc was the most stable of all the characters, keeping his personality and most of his speeches through the three major revisions that marked this early phase of the work. The personalities of Frodo and Odo Took were less clear-cut. Frodo Took began life with Frodo Baggins’ otherworldly air and much of Sam’s dialog — but in Standard English. Frodo Took is the character who is always first to notice what’s happening in the distance. Stubborn Odo, meanwhile, began to disagree with the other hobbits and to long for home and hot meals. Then, at Bree, they were joined by a hobbit who affected the most amazing transformation of all.

Strider/Aragorn’s earliest incarnation was “Trotter,” a rough-hewn hobbit-ranger notable for his grizzled air and wooden shoes (think Harvey Keitel, not Viggo). How he managed the stealthy and often perilous life of a ranger while clomping about on wooden shoes, I cannot imagine. Though Tolkien played with the idea of making Trotter be Bilbo in a clever disguise, he decided that Trotter was Peregrin Boffin, the grandson of Bilbo’s Aunt Donnamira Took. Peregrin was one of the young Shire hobbits who ran off to follow Gandalf. While helping Gandalf track Gollum, Peregrin had been captured, imprisoned and tortured in Mordor but finally had managed to escape. (At one point his wooden shoes are described as prostheses.)

As he got deeper into his narrative, Tolkien had a growing awareness that the jokey, overbearing and often ridiculous Bingo was not the right hobbit for this story. The character of Frodo Baggins first emerged after the Nazgul’s attack at the Ford at Rivendell. Perhaps the stabbing made Tolkien realize that Bingo was too lightweight a character to be the hero of the novel. Sam Gamgee is also first mentioned at this time and quickly managed to carve out a leading role for himself at the expense of Odo Took.

With the coming of Sam, Tolkien decided that he had one hobbit too many and resolved to get rid of Odo. Christopher Tolkien, however, was fond of Odo and begged for a reprieve. Tolkien spent a great deal of time waffling between his desire to rub out Odo and his need to please his son. He tried to solve his Odo problem by alternately giving Odo a bewildering assortment of new names and personalities, and by failed attempts to kill him off. In a classic display of hobbit resilience, Odo/Frodo/Folco/Faramond/Hamilcar/Fredegar/Peregrin/Pippin — to simplify matters, Christopher Tolkien refers to this composite character as “Character X” — could not be suppressed. Despite Tolkien’s resolve that “if any one of the hobbits is slain it must be the cowardly Pippin doing something brave,” and his repeated efforts to write him out of the story, “Character X” just kept reappearing with a new name, but with the same pluck, energy and irrepressible appetite. And, in classic Tolkien fashion, the attempt to write one character out of the story led to the invention of a whole army of hobbit clones.

Finally, Tolkien decided to blend the character of Odo with that of Frodo Took, the abstracted, dreamy hobbit. Frodo Took slowly began to morph through many name changes into Peregrin Took. He became outgoing and developed a swagger and definite “Odo-esque tendencies.” He also began speaking dialog that later became Pippin’s. Meanwhile, Odo’s less desirable qualities (gluttony and cowardice) were passed on to stay-at-home hobbit Fredegar “Fatty” Bolger. Thus, Odo provided the nucleus for two characters, Pippin and Fatty Bolger.

Boisterous Bingo, meanwhile, lost his smugness and air of entitlement and slowly acquired Frodo Took’s gentle otherworldliness and later his first name. While Frodo Took was dreamy and abstracted, the new hero of the story, Frodo Baggins, is also over-polite, repressed and plagued by self doubt — qualities that aren’t surprising given his childhood experience as a poor orphan relation in an overcrowded hole, overshadowed by his 101 Brandybuck relatives. An air of loss seems to cling to him.

To summarize the changes in personnel:

• Odo Took briefly merges with Frodo Took and then becomes Hamilcar Bolger, then Folco Took, then Folco Boffin, and finally Fredegar “Fatty” Bolger.

• Frodo Took becomes Folco Took becomes Faramond Took becomes Pippin.

• Bilbo’s son Bingo Baggins becomes Bilbo’s nephew Bingo Bolger-Baggins becomes Bilbo’s cousin Frodo Baggins.

• “Trotter” is revealed to be Peregrin Boffin, then Fosco Took (Bilbo’s first cousin), and very briefly, Bilbo in a clever disguise. Then, he ceases to be a hobbit altogether and becomes Aragorn/Elfstone/Ingold, heir of Elendil.

While most writers will prepare for big surprises by foreshadowing and larding the text with subtle clues as to what is to come, Tolkien often will spring his surprises on an unprepared reader. Only later as the text unfolds does he explain the surprise in a way that makes it seem inevitable, organic to the plot and right. Instead of having the clues handed to him/her on a plate in advance, the reader has to fit the new information into his/her knowledge of what has gone before. The information has to be pieced together the way we process information in real life — retrospectively. This is more difficult than just following where the clues seem to lead. It increases the buy-in for many readers because they have to work a bit for their pay-off. I’d always thought this was a carefully prepared effect designed to illustrate the workings of divine providence. It turns out that Tolkien was as clueless as his readers.

In a letter to W.H. Auden, he wrote, “I met a lot of things on the way that astonished me… Strider sitting in the corner at the inn was a shock, and I had no more idea who he was than had Frodo. The Mines of Moria had been a mere name; and of Lothlórien no word had reached my mortal ears till I came there… I had never heard of the House of Eorl nor of the Stewards of Gondor. Most disquieting of all, Saruman had never been revealed to me, and I was as mystified as Frodo at Gandalf’s failure to appear on September 22.”

By the time he reached the Two Towers section of the book, Tolkien would write: “I have long ceased to invent: I wait till I seem to know what really happened. Or till it writes itself.”

Christopher Tolkien notes that the earliest manuscripts of LotR are full of marginal questions such as “Why was Gandalf delayed in meeting the hobbits at the Prancing Pony?” “Why did everyone just happen to show up in Rivendell for Elrond’s council?” And repeatedly, “Who is Trotter?” This gives his work an air of unexpectedness; Tolkien constantly surprises his readers because he himself was constantly being surprised by his story.

An example of Tolkien’s use of unexpected surprises is found in his explanation of why the Dwarves had to flee Moria. In The Hobbit and early in LotR it is mentioned that the Goblins (Orcs) drove the Dwarves out of Moria. In the Moria chapters of LotR, however, a previously unknown creature, the Balrog, makes a surprise appearance, and it is explained that the dwarves “delved too deep” and awakened an ancient horror. As in real life, one is constantly getting new bits of information that alter one’s perception of a situation. Instead of weakening the sense of reality, these seemingly contradictory bits of information deepen the sense of reality and reinforce the notion that Moria is a fearsome place.

The evolution of the character Galadriel is another instance of Tolkien surprising himself. Galadriel’s mirror originally belonged to Celeborn. Galadriel was originally a fairly conventional queen and not a powerful seeress. As Tolkien wrote, however, Galadriel emerged from Celeborn’s shadow to be revealed as one of the great rulers of Middle-earth. In creating Galadriel and Celeborn, Tolkien created huge problems for himself. Galadriel mentions that she and Celeborn had dwelt in Lothlórien “since the Mountains were reared and the Sun was young.” She also says that she was a member of the White Council (later she adds that it was she who summoned the White Council). How is it, then, that two such ancient and powerful elves weren’t mentioned in The Silmarillion? Tolkien had to revise his mythology to incorporate these new characters. Galadriel’s back history became unmanageable as she went from being unmentioned to being a central character; (in The Unfinished Tales, it is Galadriel’s disdain for Feanor that indirectly leads to the creation of the Silmarils and to all the misfortunes of elves and men in Tolkien’s cycle of tales). The need to write Galadriel into the mythology was one of factors that led to Tolkien’s being hopelessly entangled in rewriting The Silmarillion for the rest of his life.

The manuscripts also show how Tolkien could take the merest glimmer of an idea and run with it. For example, a seemingly inconsequential talk about houses where the hobbits ponder the question “Could you sleep on an upper floor?” for an excessive amount of time leads to the invention of the elf towers and to Tolkien’s pithy description of a key element of hobbit psychology: “They do not build towers.”

The Return of the Shadow brings the company to Rivendell, and the original Fellowship is formed, which consisted of Frodo, Gandalf, Boromir, Trotter, Sam, Merry, and Falco/Faramond/Pippin. Legolas and Gimli have not yet been thought of. The book concludes with the company discovering Balin’s tomb in Moria and a brief outline of the loss of Gandalf (he wrestles with a Black Rider, not a Balrog).

More than a year passed between the writing of the material in The Return of the Shadow and the material in Part 2 of The History of LotR, The Treason of Isengard, (1940-1942). The Treason of Isengard marks a critical stage in plot formation. It was during this period that:

• After much complex morphing “Character X” becomes Pippin

• Trotter becomes a man variously named Aragorn, Elfstone or Ingold

• Frodo begins to have prophetic dreams

• Saruman is first mentioned, and the story of his imprisonment of Gandalf evolves

• The Council of Elrond chapter is written and rewritten five times

• Galdor, later Legolas, is introduced

• The color coding system of Wizard ranking is established

• The War of the Last Alliance is described, along with the History of the Kingdom of Ondor (later Gondor)

• The Members of the Fellowship are decided on

• The character of Galadriel first emerges

• The first map of LotR is presented

• Rohan is invented

• Treebeard the giant man becomes Treebeard the Ent.

Six black and white illustrations are included in The Treason of Isengard, and there is also an appendix on runes.

Vol. VIII: The War of the Ring (1944), Part 3 of The History of LotR

After Gandalf was lost in Moria, Tolkien took a long break in the writing of LotR. He stopped work in December 1942 and resumed in April 1944. Tolkien’s main preoccupation in The War of the Ring was chronology. Because the company had split up, and he was cutting between the dispersed members of the Fellowship — Frodo and Sam in Mordor, Merry and Pippin in Fangorn Forest and Aragorn, Legolas, Gandalf and Gimli in Rohan — Tolkien had difficulty bringing the different threads of the narrative into chronological harmony. Because he wanted to show that the seemingly random fortunes of each character were part of a larger pattern, it was necessary to link them through their shared experience of the natural world. He became obsessed with the synchronization of the characters’ movements, the weather and the phases of the moon. If a full moon or a great storm is mentioned in one part of the story, he had to make sure that Frodo and Sam, Merry and Pippin, Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli all experience it at the same time in the chronology.

Tolkien’s close attention to the phases of the moon put me in mind of a paradox among his readers. They seem to be split into two camps: those who think his descriptions of nature are more vivid than the real thing, and those who find them pallid and lifeless. I think this has to do with Tolkien’s use of some subtle, almost subliminal, tricks of language that don’t register with everyone. In addition to the use of poetic devices in his descriptive passages that I mentioned earlier, Tolkien also used anthropomorphic language to give an aura of volition to natural and inanimate objects. Here’s an example from The War of The Ring:

“The road passed between walls of rock and led out onto a wide upland… Beyond it was a dark wood that climbed steeply on the sides of a great round hill; its bare black head rose above the trees… two long lines of unshaped stones marched from the brink of the cliff towards it and vanished in the gloom.”

In Tolkien’s writings, mountains don’t just stand there, they “march” — and not aimlessly either — they are always headed toward a goal: “the East” the horizon, the dawn, etc.

The War of the Ring ends with Frodo’s capture by the orcs. From 1944-1946, Tolkien did no work on the novel because he was waiting to find out how Frodo got out of this mess. During that time, Tolkien worked on The Notion Club Papers, another attempt at a time travel novel.

The War of the Ring contains 21 black and white illustrations, mainly Tolkien’s sketches of the landscapes found in The Two Towers and maps of the terrain. Being a native of Washington, D.C., I was totally charmed by the throwaway line in one of the many plot outlines found in this volume: “Frodo toils up mountain to find crack.”

Sauron Defeated — the End of the Third Age (late 1946-1948). Part 4 of The History of LotR, Volume IX in HoMe. Also includes The Notion Club Papers and The Drowning of Anadûnê.

The major part of this book deals with Frodo and Sam in Mordor. There are nine black and white illustrations that depict events in The Return of the King, and seven calligraphy pages from The Notion Club Papers.

Christopher Tolkien’s practice in The History of LotR is to only present material that is significantly different from the final form of LotR. In the first three volumes of The History of LotR, this approach gave readers a whole lot of divergent material. By the time he wrote the material that is in Sauron Defeated, Tolkien had a good sense of where his plot was going. Hence ther are fewer surprises and a whole lot more of Tolkien’s compulsive rewriting. In a rewrite of the Rivendell banqueting scene, for instance, Tolkien can’t decide whether Elrond’s daughter Finduilas (later Arwen) should be sitting with the guests or serving wine. He rewrites the scene over and over again, with Finduilas sitting, standing, standing, sitting over and over and over again like an overwound jack-in-a-box.

Sauron Defeated does contain some dramatic divergences from the published LotR. Frodo’s role in “The Scouring of the Shire” is almost the exact opposite of what appears in the novel. In Tolkien’s original conception of the Scouring of the Shire, Frodo is portrayed at every stage as “an energetic and commanding intelligence, warlike and resolute in action.” He kills several of Sauron’s bullies and leads the resistance. Tolkien’s comment on Frodo’s role in Sauron Defeated seems like a parody of the account in LotR. In Sauron Defeatedhe writes, “Even Sam could find no fault with Frodo’s fame and honour in his own country… it was plain that the name of Baggins would become the most famous in Hobbit-history,” while in The Return of the King he says, “Frodo dropped quietly out of all the doings of the Shire and Sam was pained to notice how little honour he had in his own country.”

Tolkien had written an Epilogue for LotR that was deleted before publication. It is reprinted here. The Epilogue takes place sixteen years after Frodo’s departure from Middle-earth. Sam, Rosie, and their eight children are preparing for a visit from the King and reviewing the events of the intervening years. Imagine the most cloyingly sweet sentimental passages in Dickens enacted by the Smurfs and you have a good idea of how the Epilogue reads. The Epilogue’s alternate ending also weakens the impact of what has gone before. The sugary depiction of Sam and Rosie’s idyllic family life deflects attention from the great cost of the peace — nothing less than the disenchantment of the world. Postwar Middle-earth has no room for the beauty of the elves, the magic of the wizards or the decency of Frodo.

Included in Sauron Defeated is The Notion Club Papers, the story Tolkien worked on during his year and a half hiatus in LotR (1944-46). The novel seems to have begun as a playful critique of C.S. Lewis’ space travel novels. Many years earlier, Lewis had written a critique of Tolkien’s Lay of Leithian under the guise of a scholar of medieval English examining a newly-discovered manuscript. Tolkien therefore presents the minutes of a club of Oxford dons of the 1980s who meet to discuss Lewis’ writings on space travel. Tolkien’s Notion Club is modeled after the Inklings, and initially the members of the Notion Club are very similar to members of the Inklings; inside jokes abound.

The story begins with some good advice for writers of Science Fiction as the dons discuss how an author makes a spaceship credible. Tolkien sees Science Fiction writing as paradoxical because spacecraft are “less probable — as the carriers of living, undamaged, human bodies and minds — than the wilder things in fairy-stories; but they pretend to be probable on a more material mechanical level… I have never met one of these vehicles yet that suspended my disbelief an inch off the floor… the universe can’t be tricked by a surname with ‘-ite’ stuck on the end.” He lambastes authors who gloss over the difficulty of creating a convincing spacecraft with pseudo-scientific mumbo-jumbo, for impressive scientific jargon cannot mask a badly conceived fictional world. Science Fiction writers need to make their hardware and fantastic worlds credible because they are no more based in fact than “an old-fashioned wave of a wizard’s wand… Real fairy-stories don’t pretend to produce impossible mechanical effects by bogus machines.”

The conversation shifts to a discussion of myth. One of the dons says, “I don’t think any of us realize the daimonic force that the great myths and legends have. From the profundity of the emotions and perceptions that begot them and from the multiplication of them in many minds — and each mind, mark you, an engine of obscured but unmeasured energy. They are like an explosive: it may yield a slow and steady warmth to living minds, but if suddenly detonated, it might go off with a crash… [it] might produce a disturbance in the real primary world.” Another character speaks of legends that “come to life of their own and… will not rest.” Not surprisingly, the Oxford dons are soon channeling the spirits of the doomed Númenoreans and travelling (via astral projection) to Anglo-Saxon England. English weather takes a turn for the worst as the after effects of the Númenorean tidal wave spill into the twentieth century, causing “the great storm of 1987.”

From there, Tolkien makes another attempt to write of drowned Númenor/Atlantis using much of the material from The Lost Road. Tolkien couldn’t write a story without inventing a bevy of languages to go with it, and appended to The Notion Club Papers is a report on the Adunaic Language of Númenor, together with two other versions of the Númenor material, “The Drowning of Anadûne,” and the Third Version of the Fall of Númenor. Once again he got stuck. The incredible success of LotR caused him to focus on revising The Silmarillion and precluded his returning to this manuscript.

For me, the biggest surprise in The History of LotR is that there is no account of the moment when Tolkien must have looked at his manuscript and said to himself, “Wait, this isn’t just an adventure story! It’s about God, the Universe and all that!” Such a moment must have existed, for in his “Letters,” Tolkien wrote that he’d written God into the narrative of LotR unconsciously in the first draft and consciously in the revisions. I would have given a lot for a first person account about how it must have felt when Tolkien discovered that his “light-hearted children’s story” had somehow grown into something truly great.

The History of LotR is vague on how the final revisions occurred. I would have liked to have learned how long the revisions took, how Tolkien revised, how the manuscript reached its final form, and how the great “niggler” finally let it go.

The History of LotR is a treasure trove for academics and the severely hobbit-addicted. Of all the History of Middle Earth Series, these four volumes will probably have the greatest appeal to the general public, since they deal with LotR, Tolkien’s best-loved and most accessible work. Due to all of Tolkien’s revisions, however, it will be a very hard slog for the general reader.

Part III: Volumes X through XII

The final part of The History of Middle-earth consists of three volumes:

Vol. X: Morgoth’s Ring

Vol XI: The War of the Jewels

Vol. XII: The Peoples of Middle-earth

Vol. X: Morgoth’s Ring: The Later Silmarillion, Part One, The Legends of Aman

Fans of Tolkien’s cosmology say that this is “The Book.” It is a revision of The Silmarillion in the light of changes and additions to the mythology that appeared in LOTR. It also is Tolkien’s first step toward a radical re-envisioning of the foundation myths of Middle-earth.

After he’d completed LOTR, Tolkien returned to The Silmarillion with the intention of creating “one long saga of the Jewels and the Rings.” He set to work creating the back-story that would make the two separate works one. To do this he had a lot of explaining to do. He’d also become dissatisfied with his earlier creation myths — how could sophisticated creatures such as the Elves believe in a flat earth? And how could they have existed before the creation of the sun? This volume covers his remaking of much of the mythology of Middle-earth. It also fleshes out Tolkien’s conception of the nature and customs of the Elves. It includes in-depth information on their conceptions of death, reincarnation and the afterlife, as well as their marriage, child-rearing and naming customs. Also included is “Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth,” a long dialog between the elf, Finrod, Galadriel’s father, and Andreth, a wise woman from the race of men. “Athrabeth Finrod ah Andreth,” is a masterful work of imaginary ethnography as the elven king and mortal woman discuss the estrangement between elves and men, and the two races’ differing conceptions of time, the afterlife and the universe.

In Morgoth’s Ring, Tolkien attempts to come to grips with the problem of evil and punts. He gropes for a credible motivation for Sauron and his master Morgoth’s rejection of goodness. He also attempts to explain why the Valar, the guardian angels of Middle-earth, are so inept. The Valar constantly meddle in Elvish affairs for the worst and absent themselves when divine intervention is really needed. They also play favorites. The great hero, Turin, gets no divine help in dealing with Morgoth’s curse, while Frodo Baggins is constantly being rescued by the Vala, Elbereth/Varda, the Queen of the Stars.

In explaining the origins of the orcs, Tolkien ties himself up in knots. If orcs were descended from captured Elves or were a separate species, then they very likely had some sort of soul and therefore might be redeemable. This made “the only good orc is a dead orc” stance of LOTR’s heroes morally questionable. Perhaps because he is writing from an elvish tradition (he claims to be using elvish documents translated by the Englishman Eriol/Aelfwine), Tolkien seems dubious about his earlier theory that orcs were descendants of corrupted elves. Therefore he puts forward two alternative and ultimately unsatisfactory theories regarding the origins of orcs:

1) Orcs were a pre-existing species that Morgoth discovered and corrupted, or

2) Orcs are beasts or autonoma animated by Morgoth.

Tolkien rejects the first theory because, if orcs were a preexisting species that was corrupted by Morgoth, they would originally have to have been created by God. Morgoth could not create life, he could only corrupt that which already existed. The fact that orcs had independent wills and used language indicated that they possessed some immortal spark, and Tolkien could not envision God’s permitting Morgoth to irrevocably damn a whole race and to make that state inheritable. Tolkien also rejects the idea that orcs were beasts or autonoma animated by Morgoth because, for him, the ability to use language implies the presence of a soul. Also, the idea that Morgoth and Sauron would supply the orcs with every thought and word they uttered, even the insubordinate ones, is hardly credible.

Tolkien’s attempt to remake his mythology was abandoned in the early 1950s. Christopher Tolkien attributes this to “despair when negotiations with a new publisher on a plan to publish both works [LOTR and The Silmarillion] collapsed.”

Vol XI: The War of the Jewels: The Later Silmarillion, Part Two, The Legends of Beleriand

This volume covers the last six centuries of the First Age. It’s a post-LOTR elaboration of the stories that were first presented in The Book of Lost Tales, Part II. The War of the Jewels consists of four parts:

Part I: The Grey Annals

Part II: The Later Quenta Silmarillion

Part III: The Wanderings of Húrin and Other Writings Not Forming Part of the Quenta Silmarillion

Part IV: Quendi and Eldar

“The Wanderings of Húrin” is especially notable. It is a continuation of the tragic story of “The Children of Húrin.” In The Book of Lost Tales, the tragedy ends with the suicides of Túrin and his sister. In this continuation, Túrin’s father, the heroic elf-friend Húrin, is finally set free from Morgoth’s dungeon where he has languished for almost thirty years. He arrives in his native land just in time to witness his wife’s death from starvation, and in typical family style, revenges himself on all the wrong people. Great elvish empires fall like dominoes in Húrin’s misguided search for justice, the balance of power in Middle-earth is altered, Morgoth is strengthened and the stage is set for the great war that ends the First Age.

Part IV of the Book, “Quendi and Eldar,” explains the evolution of the Elvish languages, which is problematic because one would assume that a deathless people would not forget their mother tongue.

The final volume of The History of Middle Earth is The Peoples of Middle-earth, Vol. XII.

Part I of The Peoples of Middle-earth charts the evolution of the “Prologue” and “Appendices” of The Lord of the Rings. In other words, this section presents the notes to the notes. This may seem like the height of compulsiveness, but this material gives a new perspective on how Tolkien viewed his creation.

Tolkien wrote so voluminously about Middle-earth that much of the back-story that originally had been part of the text of LOTR was moved out of his main storyline and into his prologue and appendices. This is particularly true for the Hobbits and for Aragorn.

As Tolkien wrote LOTR the Hobbits began to do what every writer hopes his/her characters will do; they developed lives of their own and they began to chat. Being Hobbits, they chattered about cozy, homey things: pipeweed, geneaology, and Shire gossip. Tolkien and his son Christopher loved Hobbit small talk, but C.S. Lewis and other early readers declared that a little Hobbit chatter went a very, very long way. Therefore, much of this material was either relegated to the prologue or appendices or dropped.

Aragorn had a long history of involvement with principle characters in LOTR, such as Elrond, Galadriel, Gandalf and Denethor. Tolkien had to write up a complete back-story for Aragon to ensure that his early adventures fitted consistently with the rest of the narrative. Much of this back-story (Aragorn/Thorongil’s service to Denethor’s father and the Tale of Aragorn and Arwen) ended up in Appendix A of LOTR.

The notes also fit the story of The Hobbit into the larger context of the War of the Rings. Gandalf did not join the dwarfs’ mission to kill Smaug the Dragon out of a desire for booty, but so that he could gain a strategic advantage over Sauron.

These notes provide some fascinating perspectives on Middle-earth. In one early draft of the prologue, for example, Tolkien mentions that some hobbits were not “pure bred.” This brings up the question of who or what they might have bred with. Men were their closest relations, but as Cassie Claire points out in her “Very Secret Diaries”, such relationships would have required stilts. Could the Shire gossip that a Took ancestor once took a wife from faerie be more than mere cattiness?

In his discussion of Hobbit names, Tolkien plays a curious game with his reader’s sense of reality. The revelation that Frodo was not “Frodo” but “Maura,” Sam was really “Banazîr,” Pippin “Rabanul,” Merry “Kalimac,” and The Shire was actually called “Suza-t” created an off-center, cold-water in the face sort of feeling. I initially felt a distancing effect, a sense of estrangement from characters that I had known for most of my life. The illusion of reality that Tolkien had so carefully created in his other writings flickered for a moment, and then I found myself thinking, “Well, he’s translating from the ‘Red Book of Westmarch,’ of course things are going to be a little different.”

Part II of The Peoples of Middle-earth contains two late, unfinished stories. “The New Shadow” is a fragment of an unfinished sequel to LOTR that was begun and abandoned in the 1950s. The manuscript consists of about four pages. It is placed one hundred years into the Fourth Age. Aragorn’s son Eldarion is the high king. The youth of Gondor are bored with tranquility, sweetness and light. They secretly dress up as orcs and worship a god of darkness who may just be Sauron, Lord of Abominations, back for Round IV. The protagonist of the story, “old Borlas of Pen-arduin,” is the younger son of Beregond, the soldier of Gondor who befriended Pippin in the Minas Tirith chapter of “The Return of the King” (Borlas’ older brother was the child who showed Pippin around Minas Tirith). The story opens in Borlas’ garden, where he is having a chat that with a young friend, Saelon, who may just be a servant of The Enemy. After four pages, Borlas faces an unknown menace and the story abruptly cuts off.

The second unfinished story is “Tal-Elmar,” the story of the coming of the Númenoreans to Middle-earth, as seen from the point of view of the wild Púkel-men. The fragment suggests that this was to be a story of an aboriginal race wiped out by a ruthless, technologically more-advanced invader. The hero of the story suffers from divided loyalties: he looks Númenorean, but has been raised by the Púkel-men. His gentle soul estranges him from both camps.

At his death, Tolkien’s dream of making The Silmarillion and LOTR “one long saga” seemed unrealizable. The Silmarillion was an unpublished jumble of varient manuscripts. The connective tissue that was to join The Silmarillion with LOTR seemed to be missing. In his editing and publishing of his father’s manuscripts, Christopher Tolkien gives us some idea of what Tolkien’s great work might have looked like.

In part one of this review, I listed some of the reasons why reading The History of Middle-earth was worthwhile. I’ll conclude this review with one final, and for me very compelling reason — The History of Middle-earth is a very useful reality check. In Defending Middle-earth, Patrick Curry writes of a feeling that I suspect is quite common among Tolkien’s readers. “I was overcome,” Curry writes, “by the unmistakable sense of having encountered a world that was more real than the one I was then living in… there was a definite sense of loss when I had finished.” Certainly, if I could find a way, I would move to Middle-earth in a heartbeat — Orcs and all. The world Tolkien develops in LOTR is so three-dimensional and factually consistent that dedicated readers might find the extensive rewrites and factual inconsistencies in The History of Middle-earth useful as the cold water in the face one needs in order to return to a world of suburban sprawl, gridlock and disenchantment. If you find yourself combing the papers for headlines like “Red Book of Westmarch Found” or “Frozen Hobbit Discovered in Alps,” these books are definitely for you.

Each volume concludes with an Appendix of Names and a short glossary of Obsolete, Archaic and Rare words.

(Houghton Mifflin Company, 1984; HarperCollins UK, 2003)