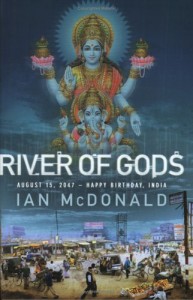

As I write this, one of the givens is that the next country that will arise to challenge the United States’ role as the world’s sole superpower will be China. This attitude has crossed the boundary from news to popular culture — it was even one of the underlying premises of Joss Whedon’s defunct sci-fi TV series Firefly. And indeed many signs point in that direction. But Ian McDonald reminds us to not forget about India. His riveting new science fiction novel, River of Gods, takes place on the subcontinent, and posits in part that the nation that now hosts the technical assistance hotlines for most of America’s high-tech companies will become a global partner and competitor in the race for tech dominance in the 21st century.

As I write this, one of the givens is that the next country that will arise to challenge the United States’ role as the world’s sole superpower will be China. This attitude has crossed the boundary from news to popular culture — it was even one of the underlying premises of Joss Whedon’s defunct sci-fi TV series Firefly. And indeed many signs point in that direction. But Ian McDonald reminds us to not forget about India. His riveting new science fiction novel, River of Gods, takes place on the subcontinent, and posits in part that the nation that now hosts the technical assistance hotlines for most of America’s high-tech companies will become a global partner and competitor in the race for tech dominance in the 21st century.

River of Gods takes place in 2047, as India nears its centennial celebration. American astronauts have discovered an anomaly: it’s what appears to be an asteroid that is older than the Solar System itself, and it contains an enigmatic spheroid artifact that appears to fortell the history and future of the Universe. It also coughs up images of four currently living humans. Two of them are known Americans. Lisa Durnau is a theoretical physicist at the University of Kansas, and Thomas Lull is her mentor and former lover who disappeared four years ago after apparently losing the battle against new laws restricting artificial intelligence to certain levels. Durnau is recruited to find Lull and the other two individuals and help unravel the mystery of their images appearing in this bizarre space artifact.

India, with its multitude of religions and gods, and in particular its role as the birthplace of both Buddhism and Hinduism, turns out to be a natural metaphor for pondering questions of artificial intelligence and the meaning of life in a world that is just beginning to grapple with the ramifications of quantum physics. Long a staple of science fiction, the theory that there is an infinity of universes fits neatly into some interpretations of Hindu theology and its pantheon, as the idea that with each person’s choice of actions a new theoretical universe is born can seem to fit inside the idea of an endless cycle of birth and rebirth, as that cycle is also tied to one’s choices and actions.

McDonald’s complex story is told from the points of view of a whole pantheon of characters. In addition to Durnau and Lull, there is Mr. Nandha, a “Krishna cop” on the front line in the battle against illegal artificial intelligences, or “aeais” as they’re called; and Aj, a teenage girl whom Lull helps in her search for her biological parents and who seems to have nearly god-like powers herself. These two are the other faces seen in the space oracle. Other human characters include Shiv, a gangster; muslim Shaheen Badoor Khan, a trusted aide to the Prime Minister; Najia Askarzadah, a Swedish-Afghani journalist; Tal, a computer programmer and FX designer who is a “nute,” one of a new surgically created, neutral third gender; and Vishram Ray, a former stand-up comic, the black sheep of the family that owns India’s main power company to whom his father has bequeathed ownership of the firm’s R&D arm.

River of Gods only slowly reveals its many plot threads to you a bit at a time, as you follow the actions and thoughts of its characters. Much is never explained, only alluded to with varying degrees of obliqueness. India has apparently been partitioned into two or more independent or semi-independent states, and the threat of war between them forms the backdrop of much of the action. The war is over water: global climate change has played havoc with the annual monsoons, and Mother Ganga, the river we know as the Ganges, is drying up. One of the Indian states has towed a huge iceberg from what’s left of the Antarctic ice sheet to the mouth of the Ganges in hopes of kick-starting a new monsoon.

Another war is being fought over artificial intelligence. The U.S. has passed strict limits banning any AI over what’s called level 2.5, which is capable of seeming human 75 percent of the time. And it’s pressuring other nations to adopt similar standards, threatening trade sanctions on those that do not — thus the Krishna cops.

Much of the action takes place in and around Varanasi, the holy city on the Ganges where many Hindus go to die and be cremated by the riverside, thus breaking their soul’s bondage to the endless cycle of birth, death and rebirth. One of my only criticisms of the book is that it’s not quite clear just exactly where much of the action does take place. The impending water war is between two states called Awadh and Bharat (where most of the action takes place) but it’s never made clear just where the borders are. And there are sometimes too many extraneous characters and entities. An entire class of persons called Brahmins — gene-engineered children who age at half the rate but live twice as long as normal folks, and who have all the rights of adults — is invented for no apparent reason other than as a foil of sorts to the nutes.

Many of the story’s underpinnings seem cribbed directly from today’s headlines. There is, of course, the problem of global climate change, but there’s also the problem of an entire generation in India into which many more boys are being born than girls, and what that could mean to their society a half-century from now.

And then there’s the science at the heart of it all. The concepts behind quantum physics, string theory and related schools of thought are so far beyond the understanding of us mere mortals that they’re hard to take seriously. McDonald and others are doing the work for us, and that’s what makes science fiction such an important genre right now. Once again, as they did with the advent of personal computers a generation ago, science fiction authors are helping us get our minds around the ramifications of ongoing scientific developments. This paragraph, which occurs toward the end of the book, does a pretty good job of encapsulating the idea of manifold universes:

Najia remembers an old childhood faery-tale told by a babysitter on a midwinter night, a dangerous one, disquieting as only the truly fey disquiets; that the faery realms were nested inside each other like baboushka dolls, but each was bigger than the one that enclosed it until at the center you had to squeeze through a door smaller than a mustard seed but it contained whole universes.

It’s also, of course, a good metaphor for a book. You can hold whole universes in your hand, between the covers. And as with those old faery tales, you need to pay attention to books like River of Gods. They contain important truths, hidden inside entertaining stories.

(Simon & Schuster UK, 2004)