Mumm me moe mummers! — James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake

Mumm me moe mummers! — James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake

The midwinter celebration, known variously as Christmas, Yule, Saturnalia, Winter Solstice, and so forth, has a very, very long history. No one’s really sure how long ago humans first recognized the winter solstice and began heralding it as a turning point — the day that marks the return of the sun. The coming of the Dark has long been portrayed in myth, story, and festival — just take a look at Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising series in which the battle between Light and Dark starts on an otherwise uneventful Midwinter’s Eve. Susan Cooper notes she was “trying to deal with the basic substance of myth: the complicated, ageless conflict between good and evil, the Light and the Dark.” Midwinter’s Eve is a date filled with both myth and tradition.

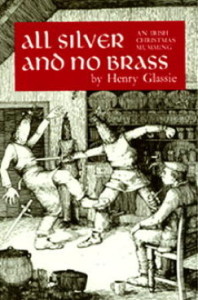

So being a fiddler in a Celtic band and of Scotch-Irish extraction, I’m very intrigued by Celtic aspects of the various midwinter celebrations. Henry Glassie’s All Silver and No Brass: An Irish Christmas Mumming is a superbly-written account of a vanishing Celtic holiday ritual that can be traced back well over three hundred years.

RuarÌ Caomhanach, an Irish musician, in an online article on Irish folk drama, says: ” Folk drama is the oldest surviving form of theatrical tradition found in Ireland. The most common forms are Wrenboys, which is the most ancient; Mumming (also sometimes known as Christmas Rhyming, although there can be slight differences between the two), which is the most textually complex; and Strawboys, an interesting variation but, unfortunately, not very widespread these days, although a form of it adapted to modern requirements is relatively common in some parts of County Clare.

The rituals of the Wrenboys and the Mummers are similar in many ways – both are performed on specific feast days (particularly December 26th) and are meant to bring good fortune to all concerned, are processional in nature, involve vegetation and animal disguise and blacking of faces, have dramatic content centered on the life-cycle, death and revival, comic crowning, parody, singing and dancing, and, finally but essentially, eating and drinking.”

What Glassie did in studying the Irish Mummers is the neat trick that any ethnographer wishes he or she could do: he gained access without going native, so he could ask questions only an outsider could ask. And ask he did! He asked and received tales about the mummers, their performances, the way mumming used to be in the old days, and the meanings of mumming. Mumming comes to life in a way that will reward both the general reader interested in a fascinating story and any serious student of Celtic folklore.

(Indiana University Press, 1975)