Gili Bar-Hilel contributed this review.

Gili Bar-Hilel contributed this review.

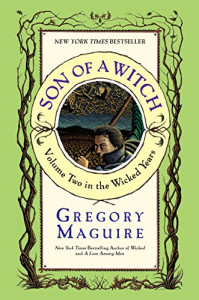

If you liked Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, you will probably like its sequel, for here is more of the same. Wicked did very well, and has been enjoying success in its Broadway incarnation, which I have got to see someday, because for the life of me I don’t understand how any musical based on that book could be enjoyable. But I digress.

I’ll come straight out and say that I did not like Wicked. I don’t think I’ve ever disliked a book more and yet owned three copies of it. People just kept thrusting the book at me, because I’m a known Oz freak, and an intellectual, and it was supposed to be a good book. I felt duty-bound to read it all the way through, though I disliked it from moment one. The same sense of duty made me read Son of a Witch.

In this sequel, the protagonist is Liir, probably (but no one knows for sure) son of Elphaba a.k.a. Elphie a.k.a. The Wicked Witch of the West, who was the protagonist of Wicked. The story flashes back to his encounter with Dorothy after her killing of the Witch, and follows him for a decade, from his meeting with a sentient elephant trapped in the body of a tribal princess — who lays upon him the task of assisting her to regain her elephant form before she can die — through his attempt to locate his possibly half-sister and childhood companion Nor in a dismal Emerald City prison. Then through his enlisting in the army of Oz and his gradual embroilment in the politics and control of the Land of Oz. Though Elphie is not alive in this book, her spirit, we are told in numerous ways, lives on.

Like its prequel, Son of a Witch abounds with atrocities, brutality and betrayal, with a good dash of the simply gruesome. But whereas the main theme of Wicked was righteousness and hypocrisy, Son of a Witch seems more concerned with fallibility as a universal and humanizing trait. Elphie was far from perfect, and so too is her son Liir. As in Wicked, no single character is purely good: the goodies are bad, the baddies are good, previously encountered characters insist on preserving their moral ambiguities and the whole thing will set your head spinning, if you let it. The only way to keep afloat with the story is to not pass moral judgment on any of the characters, but allow the plot sweep you along like a little bit of flotsam, just as life sweeps poor, passive little Liir along for most of the book.

As an Oz fan, I kept looking for traces of the familiar fairyland in this book. But Maguire’s Oz diverges from L. Frank Baum’s so sharply that it might as well have been a new (un)fairyland of Maguire’s invention. Other than a glimpse of a boy named Tip with a four-horned cow and a mean old crone (presumably, the witch Mombi from The Marvelous Land of Oz), there are no real references to other books in the Oz series beyond those already planted in Wicked. There are a few Ozzy puns, such as “sometimes I hate this marvelous land of ours.” And there is the chapter name “No Place Like It.” But for the most part Maguire exerts his energy developing his own grim vision, with no attempt to reconcile it with the Baum Oz books. That’s fine by me. I find attempts to reimagine Oz as a dystopia interesting at best, but seldom endearing. Maguire’s Oz makes more sense without trying to figure out whether it’s supposed to be some kind of commentary on the Baum Oz mythology. The less Ozzy it is, the easier I find it to relate to Maguire’s characters on their own terms, and in this sense, Son of a Witch riled me less than Wicked.

And yet I felt this book held many of the same faults as its prequel: the ponderous prose, the occasionally dithering plot, the scarcity of humor or compassion. I seem to remember one critic described Maguire’s prose as “top heavy,” and that it is, full of big words where little words would do. This is especially jarring in dialogue, where supposedly simple characters deliver bombastic sermons or too-too-clever quips. I find it affected, stilted and preachy. At least the plot flows better than that of Wicked, which had a tendency to throw in an unaccounted-for gap every time things began getting interesting. Son of a Witch follows through with a more natural storyline, and is less frustrating to read. There are some jokes cracked here and there, and some momentary tenderness – this book is perhaps not quite as relentlessly horrific as its prequel – but not enough in my mind to redeem it. For a moment I almost thought the book was going towards a happy end, which I might actually like: a final act of abandonment disappointed me.

L. Frank Baum dedicated The Marvelous Land of Oz to the stars of the first Broadway adaptation of The Wizard of Oz, and Gregory Maguire follows suit, dedicating Son of a Witch to the cast and creative team of the musical Wicked. Critics have argued that Baum wrote his sequel with the stage in mind, and purposefully included elements that would translate well to the stage, such as a battalion of female soldiers, a field of sunflowers with women’s faces, and big roles for the Scarecrow and Tin Man — stars of the stage show — while Dorothy was completely left out. One wonders whether Maguire, too, was imagining a musical staging of his sequel, when he ascribed such a central role in his book to a certain musical instrument: in one scene a chorus of barnyard animals sings to its accompaniment, in another it accompanies a morbid chorus of skinned faces. But perhaps I’m searching a bit too hard for parallels.

Gregory Maguire is clearly a talented, well educated and intelligent writer. He has my respect. I just don’t like his books. I guess I enjoy my cup of tea with less bile in it.

(HarperCollins, 2005)