We all have our personal lists, individual counterparts to those periodic lists of “most important,” “best,” or whatever the accolade of the moment might be. I have a personal list of “best fantasy series” that includes some works that might not be “great,” but several that I think arguably are. In the realm of modern heroic fantasy, in particular, I think anyone would be hard put to protest the inclusion of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Ftiz Leiber’s tales of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, Michael Moorock’s great cycle of stories of The Eternal Champion, and Glen Cook’s Black Company.

We all have our personal lists, individual counterparts to those periodic lists of “most important,” “best,” or whatever the accolade of the moment might be. I have a personal list of “best fantasy series” that includes some works that might not be “great,” but several that I think arguably are. In the realm of modern heroic fantasy, in particular, I think anyone would be hard put to protest the inclusion of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, Ftiz Leiber’s tales of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, Michael Moorock’s great cycle of stories of The Eternal Champion, and Glen Cook’s Black Company.

For those new to Cook’s series, the books are the Annals of the Black Company, the history of the last of the Free Companies of Khatovar. Never mind that no one remembers where Khatovar is, or why the companies were set free to roam the world, or even what happened to the other Free Companies. These men are concerned with the here-and-now. The narrator of these three books, the Books of the North, is Croaker, who also serves as the Company physician. He is the filter through which we see the Company’s history as it is made.

At the opening of the story, the Company is in service to the Syndic of Beryl, one of the Jewel Cities on the shores of the Sea of Torments. He is an uninspiring employer, and like most in the Company’s history is wont to demand much more than the contract provides. A great dark ship arrives bearing a legate from the Lady, who is building an empire in the North: Soulcatcher, one of the Ten Who Were Taken from the era of the Domination, when the Lady and her husband, the Dominator, ruled an empire based on fear and naked power. The Lady has escaped her captivity, bringing the Ten with her, and now has embarked on another round of conquest. Soulcatcher makes an offer that puts the Company in a quandary: their contract with the Syndic is still in effect, although it has become burdensome and dangerous. In a night of blood and terror, the Syndic has vanished, and the Company is free of its contract and soon embarks to the North.

In broad, the first three volumes encompass the Company’s service to the Lady in the conquest of the North; the rumors of the reincarnation of the White Rose, who had defeated the Dominator and the Lady four hundred years before; the great battle before the gates of the Lady’s fortress at Charm; and the Company’s change of allegiance after catching wind of a plot to destroy them by a group of the Taken. The final result is an unlikely alliance in the face of a greater threat that will destroy the Lady, the White Rose, and the Company.

So what, you may ask, is so special about the Black Company? Heroic fantasy and its predecessors among the national epics have always dealt in abstractions: honor, glory, justice, good, evil. This is reflected in the situations and characters. Frodo may be a charming depiction of a doughty English yeoman, and a thoroughly admirable man in his own right, but he is essentially Duty with hairy toes. Elric, one of the first anti-heroes in heroic fantasy (admittedly influenced by Leiber’s swashbuckling duo), is a case study in moral torment, as are all his avatars. Cook’s characters are specific: they operate on the necessity of the moment, and the moral agonies are left to Croaker’s journals. Decisions are made on the necessities, and we learn about many of them only obliquely, as in the case of the Syndic of Beryl: especially at the beginning of the cycle, Croaker is not an omniscient narrator, and he is not the one making the decisions on which the Company will operate.

It goes without saying in these stories that no one plays fair, and that includes the Company. The matter is survival, not high ideals. It’s worth noting in this context something that doesn’t really sink in until far into the series: the protagonist is not Croaker, or the Captain, or the wizard One-Eye, or any other single character that appears. The hero, if I can put it that way, is the Company. It is the Company’s survival that is paramount, an idea reinforced all sorts of ways, but perhaps most vividly in Croaker’s obsession with maintaining and preserving the Annals: that is the Company’s soul, and, as Croaker frequently points out, the Company itself, and its history, are the sole hope of immortality for each of the brotherhood.

These are rousing adventure stories, military fantasy that carries a full dose of verisimilitude, no matter how bizarre the characters may be as individuals, along with an equal dose of world weariness, no matter the excitement of the moment. In spite of their scale, which indeed deserves the term “epic,” they are tight and absorbing stories, although some have objected to Cook’s style, which is short, often choppy, sometimes jarring. All I can say in that regard, having read most if not all of Cook’s novels, is that the style is part of the character. This is not Cook’s style, this is Croaker’s style (and later in the series, as the Annals shift first to Lady, then to Murgin, then to Sleepy, the style shifts as well – there is no way to confuse a passage from Water Sleeps with one from Shadows Linger). Yes, there are characteristics that carry through Cook’s writing from story to story, but if one pays attention to the subtleties (and with Cook, one owes it to oneself to do so), it becomes apparent that the style is dependent on character and situation, and does a great deal to reinforce them: they grew together, it seems, and must be taken as a whole.

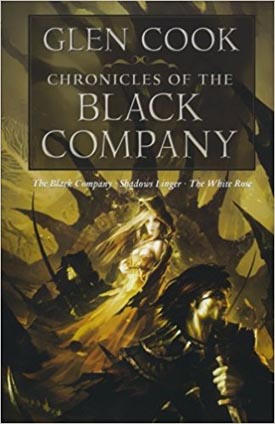

It’s a huge point in favor of Tor Books that they have embarked on a series of reissues and omnibus editions of Cook’s works. Aside from the general praiseworthiness of such an undertaking, I want to take note of one of those very rare occurrences in the publishing of science fiction and fantasy: Tor has commissioned a series of cover paintings by Raymond Swanland for Cook’s works (including the new ones) that represent, as far as I’m concerned, an almost perfect melding of artist and author: the covers are bold, chiaroscuro renderings with elements of both romance and expressionism, dark, moody, subliminally violent representations of the work of one of the masters of fantasy noir. Kudos. (Particularly since the covers in the original paperbacks range from mediocre to appalling.)

OK – should you read this book? Yes. They’re good stories. They’re even significant, in one way or another, and the packaging is superb. How can you go wrong?

For our review of the next installment,The Books of the South, see here.

(Tor Books, 2007)