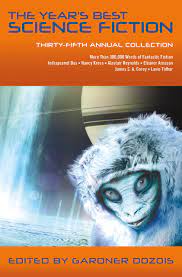

Short-form science fiction is pretty much my idea of perfect summer reading. I want something to dip into that will hold my interest at least briefly on a languid afternoon, so a big ol’ volume of great SF is just the thing. And what better sort of collection than one of the 35 “year’s best” compilations edited by the late Gardener Dozois between 1984 and his death in 2018? This volume covers his selections from short stories and a novela/novelette or two published in 2017. It’s a total of some 300,000 words in 38 stories by old masters and new talents, at least three of whom have two entries each – Nancy Kress, Rich Larson, and Indrapramit Das.

Short-form science fiction is pretty much my idea of perfect summer reading. I want something to dip into that will hold my interest at least briefly on a languid afternoon, so a big ol’ volume of great SF is just the thing. And what better sort of collection than one of the 35 “year’s best” compilations edited by the late Gardener Dozois between 1984 and his death in 2018? This volume covers his selections from short stories and a novela/novelette or two published in 2017. It’s a total of some 300,000 words in 38 stories by old masters and new talents, at least three of whom have two entries each – Nancy Kress, Rich Larson, and Indrapramit Das.

With so much good SF being published these days, any “best of” collection is sure to be a very subjective exercise. Dozois himself admitted as much in an interview with Green Man Review’s Jayme Lynn Blaschke in about 1996.

Of course, the title “Best of the Year” is a misnomer in many ways, because it’s all a matter of subjective personal taste. The book really should say something like “Gardner Dozois Liked These Stories This Year,” or “Gardner Dozois Liked These Stories the Best on the Day He Was Putting the Collection Together.” They don’t allow you to get away with such waffling in the publishing industry, where the authoritative term “Best of the Year” has a certain cachet that will make the readers buy the book.

That being said, Dozois had such a depth of experience and knowledge in the field, and quite simply such good literary taste, that I trust his judgment. I know I’m not going to like everything, but that’ll be a matter of taste, not quality.

In any collection this big, there’s going to be a lot of variety. But I noticed a few of what felt like common themes that reflect what’s going on in our world today.

- Many of them deal explicitly or in passing with climate change – whether they’re set on another world or Earth itself, they take place in a future in which Earth became uninhabitable or nearly so.

- Several of the stories have characters who are matter-of-factly gender queer.

- A lot are on themes of military conquest or colonialism, or both – and the harm these do to environments, civilizations, and the people who serve in the war or conquest. And the way veterans often feel abandoned by their government either during or after the action.

Regarding the climate crisis, it seems like nearly all of these stories refer to it in one way or another. Any terraforming story, for instance, I see as a veiled reference to the trials and tribulations of geoengineering. And while in classics like Star Trek humanity is reaching for the stars out of a yearning for adventure and growth, these days any story that involves humans settling on another world at least implies that they’re doing so because humans ruined Earth. So, for instance, in Linda Nagata’s “The Martian Obelisk,” an elderly artist labors over a monument that no one will ever see, everyone having fled the dying planet except her. In Kelly Robson’s “We Who Live in the Heart,” a close-knit clan has left the relative safety of humanity’s underground habitat on an alien planet that’s mostly ocean, to ride around inside a living submarine creature.

A couple of my favorite stories in this book are heartbreaking tales about near-future people who are giving their lives, nearly to the exclusion of everything else including relationships with those they love, to mitigate the worst effects of climate change. In Jessica Barber and Sara Saab’s intricately constructed “Pan-Humanism: Hope and Pragmatics,” we follow a brilliant young man from adolescence into middle age as he devotes himself to a scheme to turn urban spaces into water collection areas; and the equally brilliant woman he has loved since childhood who works on different schemes from her base elsewhere in the world, the two meeting only occasionally at conferences. Then in Alec Nevala-Lee’s “The Proving Ground,” a Polynesian scientist labors in similar isolation and obscurity to restore habitat for humans in Oceania, without at the same time harming the nesting grounds of seabirds. She faces a mystery when the seabirds begin suicidally attacking the wind turbines and solar panels on her island.

Sometimes the themes overlap, as in one of my favorites, Eleanor Arnason’s “Mines.” It’s a war story: Les, our female ex-soldier from a ruined Earth, is stuck on an exo-planet, struggling with PTSD, and doing the work of clearing drone-placed landmines with the assistance of a neuro-linked rodent that’s also her pet and closest friend. Until she meets and falls in love with another female soldier who’s even more damaged than her. Les was recruited for this planetary war from the slums of the U.S. The protagonist of the first story in the book, Indrapramit Das’s “The Moon is Not a Battlefield,” was similarly plucked from poverty in India to serve on Luna. Then peace was declared and he was mustered out of the service, and he’s living in a tarpaper shack on the shaft of the space elevator back on Earth, telling the story of love and loss and exploitation to a young researcher.

The story that really made me sit up and take notice, though, is Rich Larson’s second offering “There Used to be Olive Trees.” It’s a post climate apocalypse queer dystopian tale with elements that feel like fantasy. Earth’s environment is all but dead. The uber rich have removed themselves to orbiting stations, although they and their constructs, which the surface inhabitants call gods, seem to be monitoring events on the ground. The inhabitants of this place, in what used to be Spain, are divided between dwindling numbers in walled villages who have some remnants of technology and the wilder, rootless scavengers outside. A young villager, Valentin, flees over the wall because he’s supposed to become a Prophet, able to communicate with the gods via an implant, but he’s failed in three tries and fears the consequences of a fourth failure. He’s taken hostage by a scavenger about his age, Javier, who sees him and his tech as a source of tribal prestige. Their Oz-like encounters along the way reveal to both of them things they didn’t know about their respective worlds, and turn them into friends, and perhaps more. Larson’s writing somehow perfectly conveys the weirdness of this world while portraying it through the eyes of a youth who has known no other.

Suzanne Palmer’s “Number Thirty-Nine Skink” is a terraforming tale with a twist, told in first person, present tense, by a huge, sentient robotic construct left to carry on alone on an alien planet after something went horribly wrong. It’s a poignant story that evokes Gene Roddenberry’s “prime directive” in a new way. Likewise Nancy Kress’s “Canoe,” in which world explorers unexpectedly realize that somebody is trying to communicate with them, and have to quickly figure out what they’re saying and how to answer. The tone in this one is so quirkily melancholy – like <i>Wall-E</i> but with less cuteness, more menace.

Of course there are many more stories. There’s some rousing space opera, some futuristic espionage adventures, a queer romance cum virtual reality political thriller, a couple of chilling alien invasion tales … if you like SF at all, you’ll find a lot to like. Your local library is almost guaranteed to have one or more of the 35 editions of Gardener Dozois’ Year’s Best Science Fiction collections, so check one out and expand your horizons.

(St. Martin’s Griffin, 2018)