Every once in a while, being a reviewer offers a special perk, whether it’s a new book by a favorite author, a new find who stands head and shoulders above the crowd, or the chance to take another look at an old favorite. So, when the Chief asked for a fresh look at Ellen Kushner’s Swordspoint, I was more than happy to agree. Call it “mannerpunk,” call it “fantasy,” call it what you will, it is still one of the best examples of speculative fiction I’ve ever read.

Every once in a while, being a reviewer offers a special perk, whether it’s a new book by a favorite author, a new find who stands head and shoulders above the crowd, or the chance to take another look at an old favorite. So, when the Chief asked for a fresh look at Ellen Kushner’s Swordspoint, I was more than happy to agree. Call it “mannerpunk,” call it “fantasy,” call it what you will, it is still one of the best examples of speculative fiction I’ve ever read.

Leaving questions of categorization aside, it’s really a fairly straightforward story (on one level, at least — there are several stories here that all get tied together), peopled by some of the most memorable characters I’ve ever run across. It’s the story of Richard St Vier, a swordsman in the City (we are never given its name) where nobles don’t fight their own battles — at least, not those involving actual physical combat — and his “young man,” Alec, he of the aristocratic manner, questionable sanity, and mysterious past.

It all takes place in the slums of Riverside and the rarified reaches of the Hill, and involves Richard and Alec in several plots (and I mean real plots as well as well as story lines), all centered on power and its temptations.

Lord Ferris, once intimate with the Duchess Tremontaine, has designs on the highest seat in the Council of Lords; the incumbent, Lord Halliday, is very much alive and more than competent, which has no bearing on Ferris’ ambitions. Ferris wants to hire St Vier to end Halliday’s career — Richard is, after all, the deadliest swordsman of the time. Richard also becomes involved in the difficulties of another noble, the young Lord Michael Godwin, who is being pursued by the detestable Lord Horn, who doesn’t quite understand that he is no longer irresistible — but he is still vicious and petty. And stupid, as is anyone who makes an enemy of Richard, which Horn manages quite adroitly. And there is always the Duchess Tremontaine herself, Diane, who professes no interest in politics and wields great, if unacknowledged power in the Council. So we have political intrigue, swordplay, kidnapping, murder, amours, and a lot of gossip.

What impressed me most about Swordspoint, both on first reading and every one subsequent, is the elegance and clarity with which Kushner has told the story. Her narrative is lean, to the point, and yet rich enough to paint a vivid picture and elliptical enough to keep us engaged in making the connections that Kushner hints at but doesn’t belabor. There’s a degree of artistry here that is all the more remarkable for that very reticence: we participate in building this world and this story, and it’s a heady experience. It’s real poetry, very carefully not calling attention to itself.

And the people! They are among the most memorable in contemporary fiction, at least. They are priceless — even Alec, as irrational as he is, is perfectly believable, and even understandable on some level. His relationship with Richard is one of two in the novel without an ulterior motive (the other being that between Lord Halliday and his wife Mary). Kushner gives us a beautifully drawn picture of a couple who are not particularly romantic in any usual sense, but whose attachment to each other is as deep as humanly possible. As spiky and tempestuous as they might be, it becomes quite plain that there is a great deal of compromise and tenderness between them, not to mention a kind of protective ferocity in the face of outside danger that leads to a stunning climax. And in both men there is a quality of innocence, most apparent in Richard, that serves to highlight them against the machinations of the nobles. No character is skimped — they all become real, acts and motives as plain as our own — or perhaps a little more so.

Kushner mentions Trollope as an influence, to which I would add Austen and possibly Wilde — there are echoes here of that kind of clear-eyed, no holds barred detailing of the foibles of we poor humans. The milieu is built of equal parts Restoration and Georgian England, which Kushner has synthesized into a seamless universe. And that universe and its inhabitants are subject to merciless scrutiny — no one escapes.

This edition also contains three short stories set in the same milieu, and they are equally magical. “The Swordsman Whose Name Was Not Death” is in many ways a comic interlude, about a young woman who is determined to learn swordsmanship. (And I wouldn’t be surprised if this story provided the kernel of The Privilege of the Sword — all the elements are there.) “Red Cloak” is a small tale of the (possibly) supernatural and in impromptu swordfight. “The Death of the Duke” sets the stage for The Fall of the Kings, a sequel of sorts to the other works set in this universe.

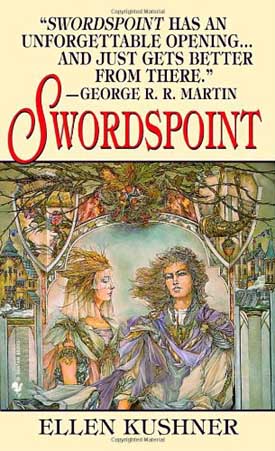

I once called this book “elegant, magical, and bitchy,” and that, I think, still catches the feel of it. George R. R. Martin said “Swordspoint has an unforgettable opening . . . and just gets better from there.” That’s only the truth.

(Bantam Spectra Edition, 2003)