Joselle Vandershoot wrote this review.

Joselle Vandershoot wrote this review.

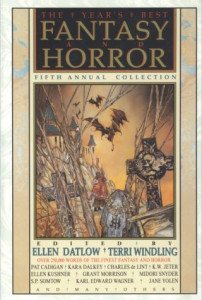

Since the first Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror anthology was released in 1988, the series has been a touchstone for remarkable and ground-breaking genre writing from around the world, and the series’ fifth edition (covering work published in 1991) is no exception. At a whopping 500 pages (not including the summary of the field for the year and honorable mentions for work the editors found notable, but were not able to include), the more than 40 short stories and poems in Volume 5 have, quite literally, something to please any number of diverse aesthetic tastes.

Readers familiar with this series (particularly the later volumes) may not be surprised to learn that 1992’s Year’s Best is weighted more toward horror and dark fantasy than toward more traditional fantasy tropes – although Windling, the editor responsible for the book’s fantasy selections, certainly does not ignore lighter, or even light-hearted, works. And damn, what horror stories they are! A significant number of Datlow’s selections do not employ squeaking doors, dark rooms and guignolesque buckets of blood to shock, disturb and upset. Rather, they plumb far more terrifying depths: those of identity, family, memory and faith. The anthology opens strongly with “The Beautiful Uncut Hair of Graves” by David Morrell (the writer of First Blood, the novel that later became the basis for the first Rambo movie). This haunting story follows an aging lawyer on a cross-country odyssey after discovering some unusual documents in his deceased father’s papers. What begins as his quest for identity ultimately turns into a harrowing search for justice and a profound exploration of Judaism. Jane Yolen’s touching YA story “Mama Gone” explores the meaning of family, and in particular the bonds between husband and wife, and father and daughter through an unexpected trope. When a young mother dies in childbirth, her preacher husband is unable to dismember her body, despite being aware of his wife’s vampire heritage. When the woman rises from her grave to terrorize the town, it is up to her eldest daughter to finish the job her father failed to do. This short and deceptively simple story examines the horror of growing up, taking on responsibility and, ultimately, dealing with a parent’s mortality.

Although Windling classifies Joanne Greenberg’s dark “Persistence of Memory” as a fantasy, I found it to be the scariest story in the book. Although I found many of the others chilling, this was the only one that literally disturbed me for hours, even days, after reading because it tackles one of my obsessions: the link between memory and identity. “Persistence of Memory” is the story of a prisoner who is visited by a denizen of Gehenna, the place of punishment for the wicked in Jewish cosmology that is frequently considered an analogue for the Christian Hell. The shade offers him the following bargain: For every memory he gives the shades in Gehenna (who pass their torment in remembering their lives and talking about the lives of others), he will be able to pass one day in prison as an automaton, without experiencing terror, misery and boredom. Without revealing too much, let me just say that the bargain is Faustian, and the questions it raises about identity, memory and their relationship to the soul are profound.

If you only read one horror story in this collection, however, be sure that story is Robert Holdstock and Garry Kilworth’s “The Ragthorn.” If you hated The Da Vinci Code as much as I did, be sure that you read this one twice; this is a re-imagining of literature, history and archaeology done brilliantly, terrifyingly, expertly right. Based very loosely on the 8th century Old English poem “The Dream of the Rood” (another word for the Cross upon which Jesus Christ hung), “The Ragthorn” follows an archaeologist’s increasingly obsessive quest to find the secret behind the large, menacing tree growing on his property, and ultimately the secret of immortality. His search leads him through the razed Library of Alexandria, The Iliad and Hamlet and concludes in a fashion that does Sophocles, Aeschylus and the writers of the original Twilight Zone proud. This story and the inimitable S.P. Somtow’s “Chui Chai” alone are worth the price of the book.

With so many wonderful subtle, psychological pieces to choose from, I regrettably found the more traditional (and consequently, often bloodier) horror stories to be weaker. Although Karl Edward Wagner’s “The Kind Men Like” begins strongly (with a young woman seeking out a ’50s pin-up model with whom she appears to be sexually obsessed), I found its payoff to be weaker than I think its set up warranted. Additionally, “The Tenth Scholar” by Steve Rasnic Tem and Melanie Tem, about a pregnant teenager who seeks vampire training and protection from Dracula himself, has several intriguing characters and high stakes (no pun intended). But I found their development to be fairly weak, which contributed to the story’s rather predictable ending. This was a pity, because I particularly enjoyed Steve Rasnic Tem’s other offering in this anthology, the world-weary dark urban fantasy story “At the End of the Day,” which follows a beleaguered delivery man’s attempts to deliver an enigmatic package to an address that appears not to exist.

Speaking of fantasy, let’s look at the other half of the book’s offerings now. Fantasy editor Windling has selected several strong pieces for her portion of the book, with something to please lovers of several fantasy sub-genres. Fans of high fantasy will enjoy Midori Snyder’s “Vivian,” a somber and non-cloyingly feminist Robin Hood story that feels very much in tune with the medieval ballads; lovers of magical realism and self-conscious narratives will thoroughly enjoy Rosario Ferre’s “The Poisoned Story,” a deconstructionist fairy tale that brilliantly subverts the roles of innocent step-daughter and wicked step-mother; fans of fairy tales and folklore will want to check out Nancy Springer’s moving “In Carnation,” which follows the last life of a cat goddess and a romantic exploit that changes her perception of humans, and “Queen Christina and the Windsurfer,” a dreamy and sometimes rather sardonic modern Greek myth with undertones of Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Little Mermaid.”

Interestingly, “The Little Mermaid” inspired more than one story in this year’s anthology. Canadian writer Charles de Lint follows this story quite closely in his “Our Lady of the Harbour,” which happens to be my favorite fantasy story in the book. De Lint uses the familiar tropes of Anderson’s piece (the loss of the Mermaid’s voice, her search for true love, the intervention of a powerful sea witch) as a springboard to explore deeper issues of human interaction, in particular the fear of romantic commitment. Not nearly as sentimental as Anderson’s tale, de Lint’s offers an explanation for human isolation and loneliness that is as bleak as it is profound.

Although much of The Year’s Best Fantasy and Horror 5 is fairly dark, those who enjoy a little humor with their speculative fiction shouldn’t scorn this book. Ellen Kushner’s “The Swordsman Whose Name Was Not Death” is a rollicking “fantasy of manners” set in the world of Riverside, which Kushner has explored in several of her books (none of which the unfamiliar reader need have read to understand and enjoy this tale – though having read them cannot hurt). Mystery writer James Powell’s “Santa’s Way” is a laugh-out-loud hilarious look at what happens to the world when a jealous mistress offs Old Saint Nick. I’m not a reader who is easily provoked to laughter, but this story had me laughing start to finish (with lines like “I almost shot the tooth fairy!” it’s not difficult to see why).

And because the poetry selections in the Year’s Best anthologies often get overlooked (and because I’m a poet myself), I would be remiss to end this review without mentioning one of its best pieces, and one that thrilled me as 10-year-old leafing through the local library’s picture books: “Pish, Posh, Said Hieronymous Bosch” by Nancy Willard (whose whimsical story “Dogstar Man” is also worth checking out). This charming tale focuses on Bosch’s frustrated housekeeper (and later romantic interest) who finds the many surreal creatures in her employer’s house frustrating:

“How can I cook for you? How can I bake

when the oven keeps turning itself to a rake,

and a beehive in boots and a pear-headed priest

call monkeys to order and lizards to feast?“The nuns were quiet. I’d rather be bored

and hang out their laundry in sight of the Lord,

than wrestle with dragons to get to my sink

while the cats chase the cucumbers, slickity-slink.”“They go slippity-slosh,”

Said Hieronymous Bosch.

Overall, the selections in the YBFH5 intrigued me, charmed me, frightened me and made me think. Ultimately, this collection (the first I have read cover to cover) has shown me why many readers and critics consider this year’s best anthology of genre work to be the best in the field. I highly recommend it not just to readers curious about what was hot in 1991, but readers who like their fantasy and horror edgy, daring and thoughtful.

(St. Martin’s Press, 1992)