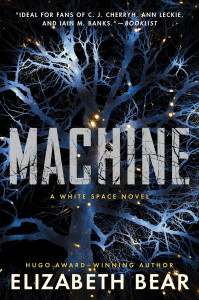

Elizabeth Bear is playing a long game in Machine, the second installment in her White Space series. The series is shaping up to be an exploration of those dark places – not to say dystopian spaces – that are always found around the edges of any apparent utopia. Via that path she’s casting her eye on some of the current ills facing humanity in the 21st century — and tossing out some thoughts about how we might resolve some of those issues before it’s too late.

Elizabeth Bear is playing a long game in Machine, the second installment in her White Space series. The series is shaping up to be an exploration of those dark places – not to say dystopian spaces – that are always found around the edges of any apparent utopia. Via that path she’s casting her eye on some of the current ills facing humanity in the 21st century — and tossing out some thoughts about how we might resolve some of those issues before it’s too late.

This one picks up sometime shortly after the events that passed in Ancestral Night, the first White Space tale, but the characters and events from that installment are only peripheral here. (And it’s not really necessary to have read the other book first, though it does give a good introduction to this particular universe.) Machine is once again told in first person from the perspective of a queer female human who is a citizen (or synizen) of the Synarche, a sprawling civilization that spans the Milky Way in the quite distant future. Our protagonist this time is Brookllyn Jens, usually just called Llyn. She’s a doctor and rescue specialist on a fast ambulance ship. And a former cop. Llyn has a genetic condition that causes severe generalized neuralgia so she uses a sophisticated, not quite sentient exoskeletal body suit to help her get around and manage the constant pain. The ship is Synarche Medical Vessel I Race To Seek the Living, but its ship mind goes by Sally. The crew includes a handful of other rescue specialists, some human, some other Systers.

The story of Machine is several things — including murder mystery, police procedural, and utopian/dystopian novel – wrapped up in a space opera. Bear also is using sizable chunks of this book to continue to build her universe and the Synarche, explaining how they work and why. Core General is a big part of that; it’s a huge multi-species Clarkean ring of a habitat-hospital in the crowded region of the Galactic Core to which Llyn is highly devoted.

The plot, in Llyn’s words, is “a grinding, slow-motion” crisis. Until abruptly, it isn’t. Bear spends a lot of ink slowly setting up a fairly elaborate scenario, a technique perfected by one of her chief influences, CJ Cherryh. Sally and her crew get sent to check out and rescue the crew of an ancient sublight ship, one of many ships that fled Terra centuries ago to escape its environmental and other disasters. That was before the remaining inhabitants learned how to “rightmind” themselves and figured out how to work together to solve those crises, then found and joined the Synarche. None of those Ark ships was ever heard from again, and this one, Big Rock Candy Mountain has been found somewhere it shouldn’t be, and shows no signs of life.

What Sally, Llyn and her shipmates find when they catch up to it is several layers of mystery. Another Synarche ship belonging to a methane-based “Darboof” Syster species is also docked to the ship, its crew unconscious at their stations and a mysterious artifact on board; a humanoid-shaped seemingly primitive AI named Helen Alloy is the only sign of life on the Big Rock Candy Mountain, unless you count the Lego-like self-replicating microbot structure that is filling most of the ship’s spaces. What humans there are, are in cryostorage, and Helen is very anxious for their safety. The ship is too huge to be towed to the Core. The challenge for Llyn and her pals is to get the Darboof ship, Helen, and as many corpsicles as they can carry to Core General to begin safely reviving them, and meanwhile figure out all the little niggling mysteries about the setup.

It’s a long time before there’s any action, really. To be honest, along about 150 pages in (on the e-book) I was thinking I wasn’t going to like this one. The careful reader will notice a lot of signs that there’s more going on than meets the eye, little clues that Llyn is missing either because she’s focused tightly on the rescue at hand or because of the blind spots she has in her own personality. Suddenly in Chapter 14, the crises start piling up, the action starts picking up, and we eventually find out that we — and Llyn — have been following a big MacGuffin around like a cat chasing a catnip mouse. Or maybe a hologram of a catnip mouse.

The action and its denoument once again involve the Judicial Goodlaw named Cheeirilaq, at this point my favorite character in the series and the only really recurring character so far, although Singer, the shipmind from Ancestral Night, does play a supporting role toward the end. The giant mantid-like Cheeirilaq spins a thread that connects the two stories and reveals them as being as much of a detective narrative as a space opera. But as with Haimey Dz in Ancestral Night, it’s Llyn and her character’s growth arc that Bear uses to tease out some of the more elaborate and deep questions that face the Synarche and our own reality-based human society. Things like faith, loyalty and trust in our own relationships with society and its institutions; and the tension between self-interest and selflessness, self-care and altruism, upon which any family, work group, and society maintains a precarious balance.

Elizabeth Bear is an entertaining writer. Here are just a few brief examples, all via Llyn’s first-person narration:

Brilliant people are sometimes terrible at being people. It goes a long way toward making their legacies complicated. I remember being taught an old ethics conundrum about whether humanity should give up space travel because Einstein was kind of a dick to his first spouse.

Feeling like you’re the protagonist of your own story doesn’t guarantee you’re going to make it to the final act of anybody else’s.

It doesn’t pay to be an asshole to people who are being careful to do their job well.

She’s also consciously carrying on many of the traditions of the SF greats who went before while creating a type of speculative fiction that is more equitable than the boys’ club in which they originated. Just for example, tools that are used in the outer space environment to extend the reach and capabilities of its user are of course still called waldos, after Heinlein’s 1942 short story by that name. It’s one of those stories that I first read in my formative years, and it has stuck with me. If you haven’t read it yet, I suggest you do so after you finish Machine for a comparative look at the way disabilities were considered then and now. And then there’s the use of “corpsicles,” coined by Frederik Pohl in The Age of the Pussyfoot, which I haven’t read — but which was carried forth by Niven in his Known Space universe, which I have, repeatedly.

In case you can’t tell, I think Machine is great science fiction, and I applaud Elizabeth Bear’s use of the space opera form to spotlight all kinds of current issues. Making us question our assumptions about ourselves and our society is something speculative fiction has always excelled at, and Bear is in the forefront right now.

(Saga Press, 2020)