Kokopelli, the humpbacked, enormous-phallused iconic flute player of the American Southwest, has become something of a pop culture phenomenon in recent decades. I’ve eaten at restaurants called Kokopelli’s, seen jewelry and collectibles made in his image, and even had a nifty vest made from a colorful material featuring the so-called “Anasazi flute player.”

Kokopelli, the humpbacked, enormous-phallused iconic flute player of the American Southwest, has become something of a pop culture phenomenon in recent decades. I’ve eaten at restaurants called Kokopelli’s, seen jewelry and collectibles made in his image, and even had a nifty vest made from a colorful material featuring the so-called “Anasazi flute player.”

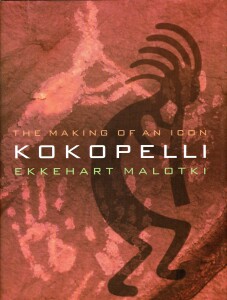

In Kokopelli: The Making of an Icon, Ekkehart Malotki sets out to trace the origins of this mythic figure, hunting down hundreds of examples of the New Mexico and Arizona rock art featuring Kokopelli and conducting extensive interviews with Hopi tribe members. The result is an exhaustive, definitive account of the origins and history of the figure. It’s also something of a disappointment.

Contrary to the press kit and dust jacket testimonials, this is not a lively read. Part one consists of an academic text, which is as dry as the arid southwest from which the rock art photos were culled. This is not, as I wrongly anticipated, a transcribed collection of oral myths and stories regarding Kokopelli. This is not Bulfinch’s Mythology. Rather, it’s a very detailed historical reconstruction of the origins and development of the flute player icon. In this, Malotki does a thorough job.

With extensively research, Malotki references preceding works continuously, investigating published theories and comments regarding Kokopelli and related figures. He exposes errors in judgements and assumptions by his predecessors, discovering confusion and conflation, semantic misconceptions and, in a few instances, outright fabrications.

He does a convincing job of tying Kokopelli’s origins to the Hopi Kachina Kookopolo. From here he traces a direct relationship between the humpbacked flute player and the equally humpbacked robber fly and cicadas of the region. The robber fly’s aggressive mating was a powerful image in the Hopi culture, and the ubiquitous cicada, with its flute-like snout and loud, buzzing “music,” was equally important. In fact, the cicada was perhaps the most significant insect to the indigenous people of the region, as it was collected and roasted as a delicacy, making up a significant portion of the tribal diet until western missionaries and settlers arrived to discourage the “uncivilized” practice.

Further interaction with whites had lasting negative effects on the Hopi religious traditions, especially Kookopolo. Nudity was an accepted part of Hopi life and religious ceremonies, and the imposition of a Puritan view of sexuality led to the ending of the ribald fertility dances and simulated sex that were an integral part of the ritual, as well as the display of the male genitals and carved wooden phalluses in said dances.

Where Malotki gleans his information directly from interviews, he provides, side-by-side, both the English translation and the original Hopi. In this, he does an obvious service to future students and researchers who will compare the translation to the original words for accuracy. This attention to detail is laudable, but unfortunately most potential readers are not researchers or academics, and the text becomes ponderous and unwieldy.

In fact, most of the information conveyed in the first half of the book is fascinating in and of itself, but Malotki’s attention to detail and focus on accuracy tend to suck the color and fun out of the words. Even the translations of Kookopolo’s outrageous antics, in which he chases eligible maidens while waving his penis in the air, comes off flat and lifeless, neither funny nor risque.

Part two focuses on six Hopi tales featuring Kookopolo and Cicada, and is somewhat more engaging. Even so, the writing remains staid and academic, the attention given to ensuring an accurate, specific translation undermining the fact that these are stories that for generations have been meant to be told and enjoyed.

To my mind, it’s the literary equivalent of dissecting the physics of a roller coaster rather than enjoying the ride for what it is. The fluid ease of the storyteller tradition is lacking, and that’s a shame, because there are some fun things here. In “The Man-Crazed Woman,” which recounts the origin of Kookopolo and how he received some potent medicine from Badger to deal with the infidelity of his abusive wife, the entertaining and ironic humor is clearly there under the surface, but for all practical purposes is dead and pickled in a jar of formaldehyde:

The man, of course, had taken the medicine Badger had given him before his homecoming … Being the man-crazed woman that she was, she was elated. Consequently, the two had intercourse there all day long. Finally, it became evening and they had supper. As soon as they were done, they went to bed. But the man did not let his wife sleep. He really worked on her and coupled with her all night long. By the time the morning dawned his wife was finally satiated. She couldn’t take any more. Evidently, her husband had become so potent that he did not let her sleep. And so both made it to the new day.

There are extensive photographic plates and drawings here, all entertaining and informative, effectively supporting Malotki’s points. Ultimately, he concludes that “Kokopelli” is still evolving and that the modern image is not traditional, and as such, the meaning and symbolism of the modern Kokopelli remains unstable and changing. That’s certainly interesting to know, but most people will never know it.

Kokopelli: The Making of an Icon may be definitive, but at its heart it remains a reference book, inaccessible for the vast majority of readers who might be attracted to the subject matter.

(University of Nebraska Press, 2000)