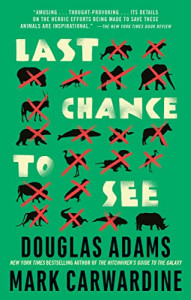

Reading Last Chance To See is a bit of an odd experience these days, what with the much-loved primary author having gone prematurely extinct himself. That being said, Last Chance To See is a joy, a reminder of what we’ve lost and an admonition that we might yet lose a great deal more.

Reading Last Chance To See is a bit of an odd experience these days, what with the much-loved primary author having gone prematurely extinct himself. That being said, Last Chance To See is a joy, a reminder of what we’ve lost and an admonition that we might yet lose a great deal more.

The book itself is deceptively simple in structure: At the BBC’s urging, Douglas Adams traipsed off to various corners of the world to visit populations of endangered species, and to report on his journeys. In the hands of a more prosaic soul, this might have turned into a numbing travelogue, a list of places visited and critters seen with not enough spark and far too much Milo-O’Shea-on-the-hoof earnestness.

Adams, however, was having none of that. His keen eye for the ridiculous was as sharp as ever, whether he’s telling the story of trying to buy condoms in China (for waterproofing a microphone, honest – it’s standard BBC procedure, apparently) or conducting a lengthy and hysterical interview with a venomous snake expert who loathes the bloody things. (“Don’t get bit” is his advice on dealing with snakebites.) The search for the rarest parrots, fruit bats, dolphins and other creatures in the world throws up many such moments, highlighting the very absurdity of the need for Adams’ quest. After all, how deranged is a world where an ornithologist desperately struggling to save one endangered species talks derisively of another’s relatively unendangered status (“Oh, there’s dozens of them!”) in order to get more time for his charges? The answer is “quite deranged,” and Douglas Adams was the perfect fellow to chronicle that insanity.

Interwoven with the humor, however, is something a great deal more serious, a realization that yes, this might be the last chance to see so many of the alternately magnificent and ludicrous creatures tottering on the brink of extinction. Adams’ initial reaction is one of surprisingly potent rage, as he boggles at the way in which komodo dragons have become a cheap tourist attraction. But as the book progresses, and he sojourns onward, rage gives way to compassion, and faintly to hope. This, perhaps, is the real journey of the book, not from komodo dragon to white rhino to Yangtze river dolphin, but rather from bewilderment to anger to something entirely different.

Last Chance To See is, sadly, a short book. It covers a wealth of locales, starting in Indonesia and swooping from Africa to New Zealand to China and beyond, and does so with grace and wit and economy. These are short expeditions, after all, and even the lengthy tango with customs in Zaire is a tale of weeks, not months. Adams and his crew go in, track down the beast in question and the locals working to preserve it, and move on. It’s a dilettante approach, but Adams made no bones about the depth (or lack thereof) of his approach. He was there to observe, not to immerse, and to see what, perhaps, Everyman should see.

Fortunately, to assist in the task of seeing the book is also lavishly bespangled with photographs of the assorted expeditions. Each is captioned by Adams in his own inimitable style. Interestingly enough, while professionally shot, they are very much tourist photos – shots of neat places and interesting people, many of whom look extremely put out by the need to pose for the idiot with the camera. But ultimately the pictures reinforce that this is an amateur’s expedition in the best sort of way, a wide-eyed and endearingly bumbling look at some increasingly rare treasures.

(Harmony Books, 1990)