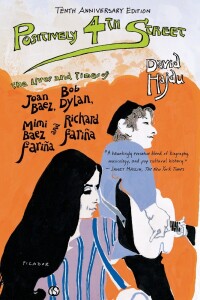

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan were key figures in 20th century American popular music. Joan’s sister Mimi and Mimi’s husband Richard Fariña were lesser lights, but important figures in the folk and folk-rock scenes. David Hajdu’s book of “the lives and times” of these four is an important contribution to understanding those lives, times and the music that touched a generation.

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan were key figures in 20th century American popular music. Joan’s sister Mimi and Mimi’s husband Richard Fariña were lesser lights, but important figures in the folk and folk-rock scenes. David Hajdu’s book of “the lives and times” of these four is an important contribution to understanding those lives, times and the music that touched a generation.

By 1960 rock ‘n’ roll had died as an important social force in the lives of the Baby Boomer generation. Elvis, Buddy Holly, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and their ilk had helped to define that generation, but the entertainment business had succeeded in taming the music, reducing it to a bland, childish, formulaic pop. American youth, restless at the tail-end of the bland and prosperous ’50s and encouraged by their President, John F. Kennedy, to become involved in civic life, were looking for a meaningful music to reflect their concerns. Many of them found it in the music of Joan Baez.

Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and others had begun the folk revival in the late 40s and through the 50s, but they were of an older generation. Baez, just 19 when she recorded her first album in 1960, was adopted as a role model by thousands of high-school and college girls, many of whom began wearing peasant dresses, long straight hair and bare feet — and trying to play guitar and sing. Her melancholy renditions of Child ballads and American mountain music struck a chord with legions of youngsters and sent record companies looking for their own version of “Joanie.”

Young Robert Zimmerman of Hibbing, Minnesota — now calling himself Bob Dylan — arrived in New York at the height of the urban folk scene and on the heels of Baez’s debut. A decided oddball, “the unwashed vagabond” (as Baez would one day portray him in song) soaked up everything he could from the music scene, latched onto key characters, and ended up recording his debut in the waning weeks of 1961. At first singing mostly traditional songs and largely mimicking Guthrie, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and other folkies, he rapidly developed his own talents as a writer, especially of protest songs.

One of the kindred spirits he found in New York was Richard Fariña, an aspiring artist, writer and musician of Irish and Cuban background. Fariña was a loveable jerk, a shameless self-promoter, and another rapid developer of his latent talents for writing poetry, fiction and music. Though several years her senior and already married, he became smitten with Mimi Baez while she was still attending high school in France. Mimi, four years Joan’s junior, lacked her sibling’s forceful personality and sheer musical talent, though she could sing and play guitar adequately, and she was by all accounts much prettier.

Positively 4th Street is largely the tale of Dylan and Baez, the two rising stars. Joan, with two or three albums under her belt and the darling of the folk circuit, fell for Dylan and began to promote him through unannounced joint appearances at her concerts. They lived and traveled together for several months, adding a much-needed romantic element to the often dour folk music scene. Richard and Mimi Fariña are foils to the two stars, struggling to come out from their shadows as artists in their own right.

Of course Dylan dumped both Baez and the world of folk and protest music and went on to become one of the superstars of pop music, eclipsing Baez’s still quite respectable career. Fariña was killed in a motorcycle accident on Mimi’s 21st birthday, after a party to celebrate it and the publication of his first (and only) book — and a mere two months before the motorcycle accident that nearly killed Dylan and changed the direction of his career yet again.

Hajdu writes with a masterful touch for this type of material, never overwriting and never forcing conclusions on the reader. Instead, he lets the subjects’ actions speak for themselves, as in the account of Dylan and Baez after a tiff, attending a show at a Boston folk club in the summer of 1963 when she was still the bigger star. Asked to step up on stage and sing a song or two, Baez declined, but Dylan accepted. When he began the third song, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right,” she walked onto the stage and sat down next to him. “Joan picked a tambourine off the floor and played it softly , tapping it against the side of the chair with her right hand. With her left hand, she began slowly rubbing the small of Dylan’s back. Bob continued the song without acknowledging her, and Joan closed her eyes as he sang.”

The author isn’t afraid to ask penetrating, if rhetorical, questions, as when the two joined a mostly black slate of entertainers and civil rights leaders at the Lincoln Memorial in August ’63. Some black leaders objected to their presence, others like Harry Belafonte saw them as important assets to the movement. “As Dylan had asked in song, who were the pawns in the game?” Hajdu writes.

He uses an effective technique of bullet-point factoids to illustrate the peak of the folk frenzy in 1963: More than 200 albums of folk music were released in the U.S., more than two dozen magazines about folk music were published in the U.S., and the “hootenanny” was everywhere, from candy bars to pinball machines.

Hajdu is also capable of cogent analysis of the music, giving a critical appraisal especially of Dylan’s groundbreaking album Bringing it All Back Home, including the cover art. The author delved deeply into existing sources of information and also conducted many hours of his own interviews. I thought he relied a little to heavily at times on the recollections of New York Times critic Robert Shelton, even after pointing out that Shelton’s veracity was called into question by his clandestine work as a promoter and writer of album liner notes.

True Dylanologists probably won’t find anything new here, but that’s not what Hajdu is trying to provide. He gives an insider’s look at four young people who were caught up in the explosion of youth culture in the 1960s, and who also helped shape it to some extent. It’s an important book, and a good one.

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2001)