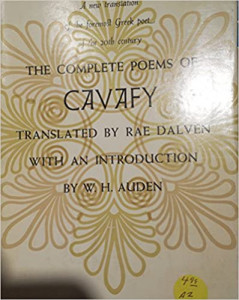

Modern Greece has produced an amazing body of literature including works by such luminaries as Nikos Kazantzakis, George Seferis, and others. One of the most significant members of this select community is the poet Constantine Cavafy. The Complete Poems of Cavafy as translated by Rae Dalven presents the body of his work for the non-Greek speaking reader, and has the added grace of including an Introduction by W. H. Auden.

Modern Greece has produced an amazing body of literature including works by such luminaries as Nikos Kazantzakis, George Seferis, and others. One of the most significant members of this select community is the poet Constantine Cavafy. The Complete Poems of Cavafy as translated by Rae Dalven presents the body of his work for the non-Greek speaking reader, and has the added grace of including an Introduction by W. H. Auden.

Auden’s thoughts on Cavafy, though brief (a mere eight pages) are insightful and greatly illuminating. One very important point that he makes about Cavafy’s poetry, addressed in relation to the problems of translating poetry while attempting to hold to the original feel and deep meaning of the works, is that Cavafy does not use imagery. I found this astonishing and had to glance at a couple of the poems to realize that it’s absolutely true: Cavafy’s poetry is direct, unadorned and yet somehow tremendously evocative. In the absence of metaphor, simile or any of the other standard tools of the poet’s trade, Cavafy builds through pure description glimpses of the world rich in association and certainly loaded with meaning.

Auden notes that Cavafy’s poetry falls into three groups, corresponding to his three major concerns: love, art, and politics.

Cafavy’s poems about love are really more about its absence: they document, often with unflinching honesty, his casual liaisons with other young men in his native Alexandria. Cavafy does not dismiss these encounters, but rather trreasures them as the wellspring of his art, as in “When They Are Aroused”:

Try to guard them, poet,

however few there are than can be kept.

The visions of your loving.

Set them, half hidden, in your phrases. . . .

And again, in “Gray”:

For a month we loved each other.

Then he went away, I believe to Smyrna,

to work there, and we nevere saw each other after that . . .

And, Memory, bring back to me tonight all that you can,

Of this love of mine, all that you can.

Aside from modern Alexandria, Cavafy speaks of ancient times – the ancient world as the kingdoms of Alexander’s Successors were, one by one, becoming clients and then territories of Rome, and of the Empire during and after the time of Constantine, when Christianity became the state religion. Many of the poems set in these times are concerned with politics, as revealed in Cavafy’s own idisyncratic way. There is more than a little irony in these poems, and a sense that the “politics” are synonyms for much larger concerns. One of my personal favorites is “Expecting the Barbarians,” a series of questions and answers addressing strange events in the city, as daily life comes unhinged “Because the barbarians are to arrive today.” Alas, night comes, the barbarians have not arrived, only a few people from the frontiers who bring the news that there are no more barbarians.

And now what shall become of us without any barbarians?

Those people were a kind of solution.

Cavafy’s mordant observations, as shown in this poem, neatly undercut our tendency to allow our lives to be disrupted because we think great events are astir. In his view, as in “Orophernes,” the events and those involved in them are likely to be ephemeral.

His history must have been written somewhere and lost;

or perhaps history passed over it,

and, justifiably, it did not deign

to record so trifling a matter.

And what was important about Orophernes, ultimately?

He who here upon this tetradrachm

has left a charm of his exquisite youth,

a light from his poetic beauty,

an aesthetic memory of an Ionian boy,

he is Orophernes, son of Ariarathes.

I am a strong proponent of economy of means, and in poetry I can think of few practitioners as adept as Cavafy in that regard. If you have any enthusiasm for poetry at all and are not familiar with Cavafy’s work, I recommend that you treat yourself to this volume – it is a real treasure. You won’t regret it.

(Harvest Books, 1951)