Connie Willis has written some brilliant satires. She has a real gift for taking the routines and the personalities we encounter in daily life and, with just a tweak here and there, holding them up to sometimes merciless and often hysterically funny scrutiny.

Connie Willis has written some brilliant satires. She has a real gift for taking the routines and the personalities we encounter in daily life and, with just a tweak here and there, holding them up to sometimes merciless and often hysterically funny scrutiny.

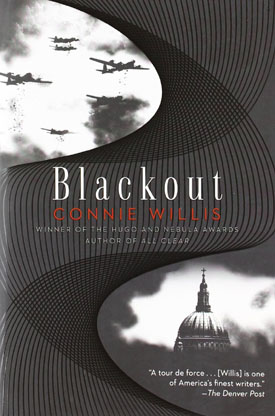

It seems that chief among her targets are academics and bureaucrats, with the bureaucratic denizens of academia at the top of the scale. That’s what we encounter at the beginning of Blackout. The beginning of the action is Oxford in 2060. It’s the center of time travel, and so, of course, being Oxford, what we have is a group of historians eager to get some first-hand knowledge of various periods of history.

Michael Davies is all set to be at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He’s had his American accent implanted, has his U.S. Navy dress whites to hand, and then, of course, his Pearl Harbor drop, the first of a long string of high-risk assignments — he’s studying heroes — is delayed. And then it’s changed: he’s going to Dunkirk, fourth on his list, instead. Without time to get his new identity prepped, he becomes Mike Davis, a reporter from Omaha. (Nebraska, not Beach — that’s another assignment.)

Merope Ward, who is serving as a maid named Eileen O’Reilly, is in the north of England in 1940, observing children evacuated from London during the Blitz. She’s drawing close to the end of her present assignment when the children start coming down with the measles — in relays: the manor at which they are housed is under quarantine for three months, long past her retrieval date.

Polly Churchill is studying the reaction of Londoners to the Blitz, also in 1940, working as a shopgirl and spending her nights in the shelters. Her usual shelter, under a church, suffers a direct hit. She’s not there, as it happens, and neither are any of her usual comrades, but each is convinced the other is a goner. And her drop point gets pretty well buried under rubble. Michael’s drop point winds up under a coastal gun emplacement, while Merope’s, in the woods on the manor grounds, just doesn’t work. At any rate, they all miss their retrieval dates.

It doesn’t really matter, because no retrieval teams are coming through. No one knows why.

The first half of this book is close to brilliant. It gives full rein to Willis’ strengths of character portrayal and satire, and also gives play to her ability to show moments of admirable and sometimes almost unbearably poignant humanity. Nothing much happens, but then not much needs to: we’re captivated by the people (and in addition to our protagonists, Willis has created a galaxy of characters, in all meanings of the word). Willis knows people very well — and I might add, for an American writer, she has a good take on the British, or at least our perceptions of the British. There are passages that are very, very funny, and there are those with which anyone who has ever had to deal with a pencil-pusher or bean-counter can readily identify, kicked up a notch by the archetypal Britishness of the combatants, from dictatorial department heads to stubborn landladies.

The down-side is that this is not the kind of story that can sustain itself for almost five hundred pages. Even a strongly character-based story needs some kind of tension to move it along, and what there was peters out about halfway through. We have a situation in which three time-travelers are facing disaster, none of them are able to do anything, and there’s nowhere to turn. This strikes me as a recipe for a potentially gripping story, but what we have is continued character development — sort of — for two hundred pages. Frankly, I found the last half of the book a trial. Imagine my dismay when I discovered that this is only the first volume.

(Ballantine Books, 2010)