When we first meet the Son of God, he’s a young boy with a lizard in his mouth. He takes the lizard out, hands it to his younger brother, who plays with it for a while, then mashes its head with a rock and hands it back to Jesus, who puts it back in his mouth and repeats the cycle.

When we first meet the Son of God, he’s a young boy with a lizard in his mouth. He takes the lizard out, hands it to his younger brother, who plays with it for a while, then mashes its head with a rock and hands it back to Jesus, who puts it back in his mouth and repeats the cycle.

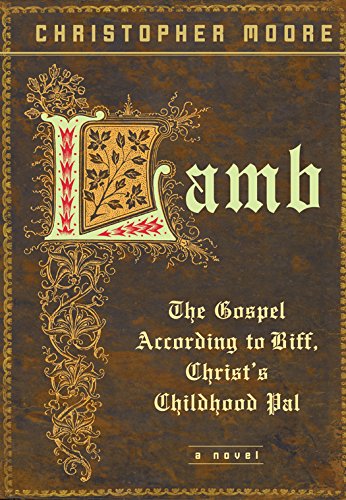

This scene in Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ’s Childhood Pal, is vintage Christopher Moore. And Lamb is his best book yet.

Moore is a popular American novelist who specializes in humorous horror, for want of a better term. Something like you’d get if Stephen King and Carl Hiassen or Dave Barry collaborated. Generally, in his five previous books, Moore has taken monsters, gods, creatures and demons from old stories, legends and myths and set them in the modern world, where they do their best to confound the lives of some confused Americans. Coyote Blue drew from American Indian mythology, Bloodsucking Fiends arose from the vampire tale, and Practical Demonkeeping presented a devil out of Christian theology.

In Lamb, however, he has done the opposite: put characters with 21st-century sensibilities inside an old story, the tale of Jesus. Or rather, Joshua, which was his Hebrew name.

The device is this: An angel, Raziel, has been sent to earth to resurrect Levi, called Biff, Joshua’s best friend. Biff is to write a fourth Gospel, telling the story of all those years between the Manger and the Ministry.

Like Neil Gaiman and Terry Pratchett in their Good Omens, Moore has great fun using a literal interpretation of scriptures. Assuming the New Testament story of Jesus is true, what must he have been like as a child? As a teenager? Moore imagines what daily life might have been like “in Bible times” as they say, and then places three modern-seeming children into those times. Three? Yes, Joshua, Biff and Maggie, otherwise known as Mary Magdalene.

Maybe they’re not really modern children, but rather just normal children, who are much the same in whatever time or place. The same goes for teenagers, of course, and things really get interesting when Biff and Joshua take off on a coming-of-age quest around central and southern Asia. And as a subplot, we follow the interactions of the stuffy and humorless angel Raziel with Biff in modern America, with its television, pizza, music, fashion, and cartoon superheroes.

Biff is a lovable rogue both as a youth in Galilee and a resurrected adult in America. He’s a lazy, cowardly, pragmatic hedonist, the perfect foil for the conflicted young Joshua. And of course both are in love with Maggie.

Moore gives us a book with fully developed main characters, set in a believable world of real people, trying to cope with the harshness of life as subjects of Rome in a far-off, dusty corner of the empire. It’s also laugh-out-loud hilarious most of the time. I can practically pick a passage at random.

“While the other boys would be playing a round of tease the sheep or kick the Canaanite, Joshua and I played at being rabbis, and he insisted that we stick to the authentic Hebrew for our ceremonies. It was more fun than it sounds, or at least it was until my mother caught us trying to circumcise my little brother Shem with a sharp rock.”

Lamb is also filled with poignant moments, as young Joshua struggles with knowledge unknown to most adults, much less children. When Joshua casually mentions to his “father,” Joseph, that Joseph may not have all that long to live, Biff tries to intervene.

“I wanted to throw my arms around the old man, for I had never seen a grown man afraid before and it frightened me too. ‘Can I help?’ I said, pointing to the half-finished bowl that lay in Joseph’s lap. ‘You go with Joshua. He needs a friend to teach him to be human. Then I can teach him to be a man.'”

There are numerous such moments in Lamb, which is one of the funniest books I’ve read in many a cubit. Or is that a centurion?

(Morrow, 2002)