The trick to enjoying Christopher Fowler’s The Victoria Vanishes is to avoid thinking too hard about it. Bear in mind that there is indeed plenty to enjoy here, much of it residing in the rich characterization of the members of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit. Once again, we’re treated to the offbeat approaches of Senior Detective Arthur Bryant and his partner in crimebusting, John May, their peers and fellow travelers at the PCU, and all the off-kilter shenanigans that go with them.

The trick to enjoying Christopher Fowler’s The Victoria Vanishes is to avoid thinking too hard about it. Bear in mind that there is indeed plenty to enjoy here, much of it residing in the rich characterization of the members of London’s Peculiar Crimes Unit. Once again, we’re treated to the offbeat approaches of Senior Detective Arthur Bryant and his partner in crimebusting, John May, their peers and fellow travelers at the PCU, and all the off-kilter shenanigans that go with them.

Women have been dying in pubs, you see. Middle-aged women with seemingly nothing in common, and whose deaths might be passed off as accidents or coincidences were the PCU not involved. But it’s not just business as usual at the Unit; Bryant has submitted his resignation, May is due for cancer surgery, and both a fractious new addition to the team and renewed enemy action on the part of Unit’s political rivals provide ominous hints that even the best things can’t last forever. And there’s something — or somethings — else behind the murders, agendas that might possibly be darker or more astonishing than one psychopath’s rampage across London’s corner pub scene.

Much of the pleasure of the book comes from the cast of characters that inhabits the PCU, who are all more than one-note players. There’s real growth and change here, both positive and negative. The book starts with the funeral of the unit’s long-time coroner and wends its way through more changes; the end of one squad member’s infatuation with another, other squad members questioning their roles and their destinations, and even long-time partners uncovering secrets that had been left buried for years. In that aspect, the book excels. For all of the oddball charm of the crimes they solve and the methods they use, the PCU is most definitely comprised of real people with their wounds, flaws, and dusty, worn-down dreams.

If there is a false note in the character side of things, it’s in the cameo made by long-standing nemeses Faraday and Kasavian. They’re there to shove the plot on its merry way, and that they do, with an evil plan that has no precedent, no warning, and no possible counter. There’s no inkling that what they’re up to is about to happen, which means when they do drop their bombshell on the PCU, it comes out of nowhere. That diminishes its impact,

There’s another issue with the book as well, one that I almost hate to call out. The real problem with The Victoria Vanishes is that it is too much a murder mystery in the literary sense, as described by Raymond Chandler in “The Simple Art of Murder.” It’s wonderfully and artfully constructed, with magnificently esoteric clues that only a polymath like Arthur Bryant could decipher, and only a deranged genius who’d grown up in pubs and had a desperate wish to be caught could leave behind in most cunning fashion, and… constructed is most definitely the word for it. As clever as the deduction might be, as fascinating as the individual clues are, as magnificently ambitious as the malefactors’ evil plans might be, they are so delicately constructed, so reliant on both murderer and detective having precisely the same set of bizarre factoids buzzing around their brains that the whole thing becomes something of a hothouse flower, unable to sustain itself outside of its rarefied and unique atmosphere. Start asking questions — why such an intricate murder plan, why did certain personages go along with it when there were certainly cheaper and easier ways to ascertain their ends, why trust such a delicate task to such a raving loony, and so forth. With each question like this raised, two more pop up their heads until the entire edifice of artifice collapses under the weight of its own improbability. It is, as Chandler might have called it, a case of having God sit in the PCU’s lap, and perhaps even settle in and make Himself comfortable there for a good long while.

And yet, there’s so much that’s light and wondrous and enjoyable in The Victoria Vanishes that it seems a shame to pick it apart. It’s far better to enjoy the pleasures it offers — and again, there are many — than to try to dissect them, better to marvel at the intricacies of the plot architecture than to call in to question whether the story’s central supports are indeed load-bearing. Take pleasure in the company of Bryant and May and the rest of their fellows, because the gents are getting on in years, and who knows how many more excursions they might have in them.

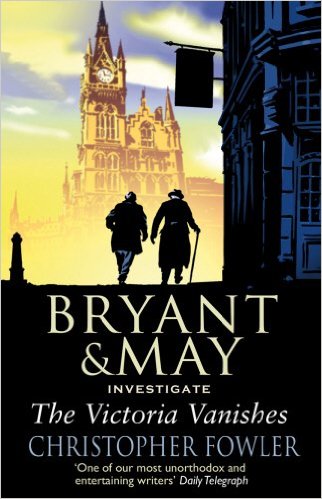

(Bantam, 2008)