China Miéville (Perdido Street Station, The Scar, The Iron Council) is renowned for the world he has created around the great, multi-species, many-storied city of New Crobuzon. Those are adult works, beyond a doubt: ferocious and frightening, full of the incandescent mysteries and fatal sins of maturity. At the same time, one of the conundrums of Miéville’s style has been the sense of a small boy peeking through his writing; the kind of little boy who delights in snot and crawly bugs, who chases his sister with a frog and forgets to take that interesting dead bird out of his lunch box. Sometimes this gleeful grossness amuses the reader in turn. Sometimes it seems unnecessarily provoking. But it has always reminded me of how young Mieville is.

China Miéville (Perdido Street Station, The Scar, The Iron Council) is renowned for the world he has created around the great, multi-species, many-storied city of New Crobuzon. Those are adult works, beyond a doubt: ferocious and frightening, full of the incandescent mysteries and fatal sins of maturity. At the same time, one of the conundrums of Miéville’s style has been the sense of a small boy peeking through his writing; the kind of little boy who delights in snot and crawly bugs, who chases his sister with a frog and forgets to take that interesting dead bird out of his lunch box. Sometimes this gleeful grossness amuses the reader in turn. Sometimes it seems unnecessarily provoking. But it has always reminded me of how young Mieville is.

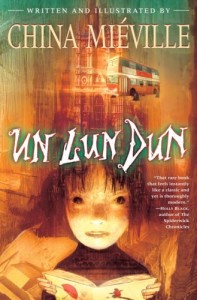

Un Lun Dun is his first actual novel for young readers, and — marvelous paradox — it is a wonderfully mature work. The writer’s voice is focused through the child’s vision like light through a ruby, becoming coherent energy, light with a sword’s edge. His previous hints of childishness become instead a clear-eyed look at fantasy, heroism, tragedy and redemption from the viewpoint of a 12 year old girl.

Zanna (she hates her given name, Susannah) and her friend Deeba are best chums, the leaders of their coterie at a London school. Zanna, although a newcomer, is charismatic and forthright (and blonde), and has charmed their circle of friends. But when peculiar things begin to happen around her, that bond begins to fray alarmingly. Wild animals approach Zanna fearlessly, strangers come up and hail her as The Chosen One. Strange mists and fogs pursue her. Finally an inexplicable smoke cloud envelopes the girls on their way home, and — while Zanna escapes — one of her friends is struck and badly injured by a blinded car. Worse, Zanna’s own father is the driver. This is all too weird and scary for most of Zanna’s friends; all of them cut her dead and desert her, except for Deeba.

Bitterly consulting over the desertion of their friends, Zanna and Deeba see something weird: a battered umbrella moving against the wind outside in the night. Pursuing it, they find a strange door into another word; and, of course, being 12-year old girls and unhappy with their own world at the moment, they walk right in. They find themselves in Un Lun Dun: literally unLondon, a skewed and insanely magical version of their own city. Much of it is wonderful and other parts are terrifying, but the most frightening thing is that the girls are eagerly anticipated. Un Lun Dun has a great enemy, whose sole desire is to conquer and consume the city, and only the prophesied Chosen One can save the world. And, according to a self-important talking Book, Zanna is the Chosen One.

This is where the adventure takes a hard left turn into Miéville’s splendidly original universe. Nothing is at it seems, even to the Un Lun Dun-ers themselves. Their great foe is as much a product of Zanna’s and Deeba’s world as of Un Lun Dun; in fact, both worlds are in peril. The prophetic Book has been treacherously edited and suffers not only a failure of prophesy but a profound crisis of faith. There are traitors in every defense the city has assembled. Worst of all, Zanna hates Un Lun Dun and refuses her destiny as the Chosen One.

But Deeba feels a growing responsibility for the people she has met there. Her ultimate decision to try and save Un Lun Dun is energized as much by outrage as by sympathy — the Book informs her than in the prophecy of the Chosen One, Deeba herself is identified as “the comic sidekick.” That would provoke anyone into heroism, and every 12-year old who reads this will understand instantly.

Un Lun Dun is portrayed in lucid, fascinating and sometimes horrifying detail. It has its natural denizens — carnivorous giraffes and an entire society of ghosts are prominent — but it is also the sanctuary and ultimate destination of everything and everyone who gets lost from the “real” world. The used up and marginal find places there, too, personified most clearly in Brokkenbroll, the Lord of broken umbrellas. In Un Lun Dun, his subjects are alive and animated, and flock like pigeons through the vast, ancient city. And there is Curdle, the bravest and most faithful empty milk carton one would ever want to meet. Curdle is frankly cute, despite — or maybe because of — being honestly portrayed as a stinky little bit of crumpled trash.

Un Lun Dun has been favorably compared to The Phantom Tollbooth (Knopf, 1961) and with good reason. It’s the same sort of straightforward story, a lively fantasy with no glitter or sugar in it. When I was 12, I loved The Phantom Tollbooth because it made sense from a kid’s viewpoint and did not talk down to me. Un Lun Dun has that same honesty and matter of fact voice. In addition, it has the same kind of fascinatingly creepy illustrations. The Phantom Tollbooth was illustrated by the immortal Jules Pfeifer; Un Lun Dun is illustrated by Mieville himself, and his work is every bit as good. These are not charming, fairy tale drawings — they are weird and wonderful and downright scary (those predatory demon giraffes are still staring out of the back of my mind). They look like something a clever kid would doodle in their school binder, which is precisely right for the book.

Miéville is clearly a writer who remembers what it was like to be a kid: below the sight lines of the adult world, with no power but one’s own ingenuity. This is a book about identity — who you are, who other people think you are, how they can make you into something you don’t want to be or never even dreamed of becoming.

It’s about the cost of identity, too, and what happens when you either let the world define you or resist it. These are Big Questions. They are major components of good children’s fantasy, and not because they are little fables suitable for the kiddies. We teach them to children because they are the people who most need to learn the lessons of how to be true to one’s self. They’re also the people most likely to really understand what it means to be forcibly shaped by the rest of the world. Un Lun Dun is just the sort of story children need, and the brilliant Mieville has made it palatable by writing a ripping good yarn to support the profound truths he weaves into the story. Give this book to your children.

(Del Rey, 2007)