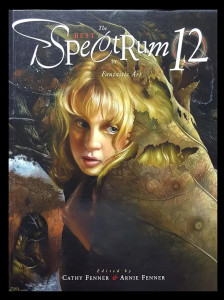

I learned early in my career as an art reviewer to avoid group exhibitions, especially those with very large themes. I find many of the same problems in discussing the newest Spectrum: disparate visions, a wide range of approaches, and, since these are all illustrations, a variety of assignments. Not an easy thing to discuss.

I learned early in my career as an art reviewer to avoid group exhibitions, especially those with very large themes. I find many of the same problems in discussing the newest Spectrum: disparate visions, a wide range of approaches, and, since these are all illustrations, a variety of assignments. Not an easy thing to discuss.

The entries fall into several categories: books, comics, dimensional works (read “sculpture,” as in action toys and maquettes), editorial, and institutional. There is also a group of unpublished works. Let me start with one major observation: they are all worth looking at. They are by turns murky, exquisite, brooding, edgy, morbid, scary (although not as scary, perhaps, as the art directors would have wished), gruesome, romantic, and sometimes raucously funny. Styles range from hyperrealism to the blatantly cartoony, and media are whatever works — oil or acrylic on canvas, watercolor, digital manipulation (and those are just the most obvious).

There are many references to high art and the traditions of illustration. Most of the images, particularly in the Books category, incorporate the hyperrealism of surrealists such as Dali and Tanguy, although they generally lack the acidity of those artists’ dream visions (the stand-outs are Eric Fortune’s Self Portrait in the “Unpublished” section, with its Magritte-like play on space, and Travis A. Louie’s Grandma Cyclops Circa 1896, also in “Unpublished,” which calls to mind the early photographs of George Platt Lynes). Linda Bergkvist’s The Boy With Golden Hair, in “Books,” bridges the seemingly unbridgeable gap between Maxfield Parrish and Baron Wilhelm von Gloeden in a luminous rendering of a seated youth. John Jude Palencar’s Wild Reel, also in “Books,” recalls the severe, barren landscapes of Odd Nerdrum, while Kent Williams’ Blood, in “Comics,” is strongly reminiscent of Egon Schiele’s tortured drawings of 1911-1913. Robert Carter’s Inner Dialogue appropriates an image by photographer Marcus Leatherdale. Gregory Manchess’ Conan of Cimmeria is a sensuously rendered painting that not only hearks back to Goya and Manet, but seems to be the only image in the entire book that views a male figure with the same romantic and subliminally erotic vision that most of the female figures receive. (This is not counting images of voluptuous and barely clad women for the hormonally supercharged teenaged male that have been a staple of fantastic illustration seemingly from its beginnings. Those are equally well-represented here. I would suppose that as long as there are teenage boys, there will be a market for teenage fantasies.)

I have favorites. Both Matt Cavotta’s Etched Oracle and David Von Bassewitz’ Ghoom caught my eye for the sheer excellence of their design, the first a prime example of the surrealist realism I mentioned earlier, the second for a masterful combination of finished rendering, sketch, and type. Jonathan Wayshank’s chilling little untitled piece combines surrealism with a bit of optical illusion to create an image that is puzzling and a little frightening. Douglas Smith’s scratchboard and watercolor illustration, Mirror, Mirror, is a refreshing break from the detailed pictorialism of most entries, giving the feel of a woodcut. The hands-down favorite, however, is Justin Sweet, represented by several entries, whose handling of watercolor is superb. His first illustration in the book, the Silver Award for Advertising, is a loose, impressionistic rendering of, perhaps, Don Quixote as seen by Fritz Leiber. His oils, enhanced by digital manipulation, are equally arresting.

“Books” does not seem able to match the range or inventiveness of the other categories. This is, perhaps, a function of publishing as a bottom-line industry driven by a few mega-houses operating on perceived marketing niches (which is, after all, a large part of the reason we have such “genres” as science fiction and fantasy to begin with). While each individually is of interest, as a group they develop a certain genetic likeness that becomes an overall sameness. “Editorial” is probably the most edgy category, and one that is overtly political, as witnessed by Thomas L. Fluharty’s Sir Hillary Poised For A Takeover (winner of the Gold Award) and several entries that are less than complimentary toward the Bush administration. Playboy, which has a history of commissioning some of the best illustration going, shows well here, especially Dave McKean’s St. Mark’s Day, a tremendously evocative drawing with collage, and Janet Woolley’s mixed-media Detroit Death City. The “Institutional” category (defined, essentially, as “none of the above”) also has some compelling entries, particularly Dave DeVries’ transformations of children’s drawings into eerily resonant nightmare visions.

Although lacking a table of contents (which would have been helpful if only for the category locations), the book does contain a “Year in Review” type introduction by co-editor Arnie Fenner, a tribute to Swiss illustrator H. R. Giger, this year’s Grand Master awardee, by Harlan Ellison (which turns out to be more about Ellison than Giger), and an index to the artists, with contact information.

I’ve always found anthologies such as Spectrum and its cohorts from the advertising industry absorbing and stimulating. Spectrum 12 is no exception.

(Underwood Books, 2005)

[Update: Spectrum is now up to its 25th volume. It us now an imprint of Flesk Publications.]