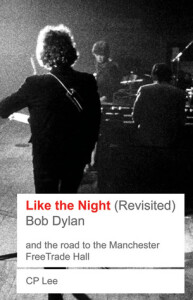

The 1966 concert at the Manchester Free Trade Hall is the most legendary single performance of Bob Dylan’s career; perhaps of the entire rock era. This concert, at which an irate fan shouted “Judas!” at Dylan, almost immediately entered the rock pantheon. C.P. Lee, a former rock musician himself and a longtime music writer, was there as a teenager; and he did an immense amount of research to come up with this, the definitive document of that auspicious night.

The 1966 concert at the Manchester Free Trade Hall is the most legendary single performance of Bob Dylan’s career; perhaps of the entire rock era. This concert, at which an irate fan shouted “Judas!” at Dylan, almost immediately entered the rock pantheon. C.P. Lee, a former rock musician himself and a longtime music writer, was there as a teenager; and he did an immense amount of research to come up with this, the definitive document of that auspicious night.

It had been nine months since Dylan “went electric,” and caused a sensation at the Newport Folk Festival. He had included electric guitar, keyboards and drums on his last two studio albums, Bringing it All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited (recorded in December 1964 and June 1965), and had made clear through the changing focus of his songwriting that he was no longer a “folk” or “protest” singer.

Dylan’s new direction may have ruffled feathers at Newport in the U.S., but in the strongholds of the folk traditionalists, particularly in the U.K., it was anathema. There, in the folk movement and the clubs where the music was performed, the rules were strict. Folk was folk, and pop was pop, and never the twain were to meet. While much of England, the U.S., and the rest of the world were in the throes of the so-called British Invasion, celebrating The Beatles and The Rolling Stones and their refreshing take on American blues and R&B, U.K. folkies remained locked in to their acoustic guitars, their “derry-downs” and their “hey-nonnie-nonnies.” They were not prepared for Bob Dylan and a group that would become known as The Band performing electrified versions of “Baby Let Me Follow You Down,” “Leopard-Skin Pillbox Hat” and “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Throughout a year-long tour of the U.S., Australia, parts of Canada, Ireland, Scotland, Paris and England in 1965 and 1966, Dylan and his band met with resistance to his new direction. His standard set consisted of 45 minutes solo acoustic, an intermission, and 45 minutes of plugged-in folk-rock. To be sure, many of his old fans (and many new ones) were able to accept both sides of the new Dylan. But at nearly every stop along the way, a good many fans expressed their distaste for the electric set. He was jeered, heckled and booed, and subjected to the group “slow hand-clap,” a peculiarly British way of expressing a crowd’s displeasure.

The situation peaked on May 17 in the industrial city of Manchester in northwestern England, in a sold-out concert at the historic Free Trade Hall. It was probably not unlike countless other shows on the tour, until the moment that someone shattered a rare moment of quiet as Dylan and the band tuned their instruments, with that piercing epithet of betrayal. It was applauded by much of the crowd, and caused a gasp of disbelief by others; and, after a few stunned moments, was answered, twice, by Dylan. “I don’t be-LIEVE you!” he snarls; then again, “You’re a LIAR!” Then he steps back from the microphone; he or perhaps guitarist Robbie Robertson shouts something that sounds like “Play Fucking Loud!” and they charge into a vitriolic rendition of “Like a Rolling Stone.”

For decades, bootleg recordings of parts of the concert circulated — it and a few other gigs were officially recorded for possible release of a live album — under the misnomer, Bob Dylan Live at the Albert Hall, which was the final date on the tour a few nights later. It was finally released by Sony/Columbia in 1998 as The Bootleg Series, Vol. 4 — Bob Dylan Live 1966 — The ‘Royal Albert Hall’ Concert. It’s a stunning two-disc set of the entire performance, acoustic on one disc, electric on the other, beautifully recorded and remastered, with an excellent accompanying booklet.

The release set Lee on the trail of the full story of the concert, which resulted in this book, first released in 1998, and re-released in 2004 with some fascinating updates. We find out, for instance, what has happened to the historic but derelict concert hall. But most interesting, we meet not one, but two men who credibly claim to have been the “Judas!” shouter.

Lee seems to be of the common school of British music writing; which is to say, sometimes more concerned with an enthusiastic style than with the rules of the Queen’s English. I don’t so much mind the occasionally purple prose — it’s rock ‘n’ roll, not Renaissance court music. But he could use a more consistent and rigorous editor, particularly in the matters of sentence fragments and unnecessary capitalization. (A sharper editor would’ve also caught it when he called the music of Muddy Waters “urban or Chicago R ‘n’ B,” rather than urban or Chicago blues.)

That said, for the most part, Lee writes with eloquence and occasional brilliance of the actual concert and its effect on him as an audience member. “There are certain moments in history when its been an astonishing joy to be alive and on the planet, specific instances when you’ve been allowed to share true genius with an artist,” he writes of the moment he heard “Visions of Johanna” at Manchester. “‘Visions’ still staggers me now after all these years.”

Practically a primer on the birth of folk-rock, Like the Night is an important book for Dylan fans and anyone who cares about rock history. It will greatly enhance your enjoyment and appreciation of the Live 1966 set (and if you don’t have it, it will persuade you that you should). And it is for the most part an interesting and entertaining book to read.

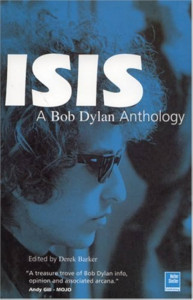

Before there was an Internet or a World Wide Web, before there were blogs, there were fanzines. Isis is one of the best-known of the Dylan fanzines, founded by British writer Derek Barker in 1985. This book represents some of the key articles culled from the ‘zine’s pages. As a compiled fanzine, this publication reads like a book-length blog. If you have no problem with that concept, and you have a near-bottomless capacity for Bob Dylan arcana, Isis is for you.

Before there was an Internet or a World Wide Web, before there were blogs, there were fanzines. Isis is one of the best-known of the Dylan fanzines, founded by British writer Derek Barker in 1985. This book represents some of the key articles culled from the ‘zine’s pages. As a compiled fanzine, this publication reads like a book-length blog. If you have no problem with that concept, and you have a near-bottomless capacity for Bob Dylan arcana, Isis is for you.

Barker himself is no great writer. In fact, he makes C. P. Lee look like Norman Mailer. (Lee, in fact, contributes a chapter about … you guessed it, the Manchester Free Trade Hall concert.) He’s an even worse editor of himself, which leads to even more egregious run-on sentences and the like than we see in Lee’s book. And some odd errors, such as referring to Rubin “Hurricane” Carter’s favorite beverage as “100 per cent proof Smirnoff” vodka. And curious sentences like this one, from a section on the making of the album Desire and the influence of Joseph Conrad: “Like many writers in English, Joseph Conrad was not born in Britain.” What the heck is that supposed to mean? In a couple of chapters about Dylan’s early life, the name of one of his friends is variously spelled as Larry Keegan or Larry Kegan, with no indication of which is correct.

Throughout, there is an odd, seemingly random use of italics: suddenly, in the midst of a sentence, a couple of words are italicized, for no apparent reason. But that’s the least of my typographic quarrels with the book, which is printed entirely in a rather light, slightly compressed san serif typeface. That might be acceptable for a fanzine or Website, but not for a book.

Some of the articles, like one seemingly interminable one about the origins of Mr. Dylan’s stage name, or the tracking down of boarding houses he lived in in Minneapolis when he was supposed to be going to college, are of just the sort of obsessive attention to trivia that one expects from an amateur ‘zine. At other times, because it’s assumed that the ‘zine’s readers know as much about Dylan as do the obsessive writers and editor, important background is left out. I’m thinking here of an epilogue written by Martin Carthy, which is appended to an earlier interview by Matthew Zuckerman, in which Carthy relates a mending of fences between himself and Paul Simon over lingering bitterness from the early 1960s. Carthy writes that he respects Simon now, and is giving up his grudge. But the editors never give any background information on what caused the bitterness, which I believe was over Simon’s appropriating of certain English folksongs from Carthy and recording them without credits.

On the other hand, some of the articles, for the very reason that they are in a fanzine rather than a mainstream press organ, get closer to Dylan than official media ever do. There are the transcripts of Bob Shelton’s 1968 interviews with Dylan’s parents, for instance. Interesting, revealing stuff. And Barker is a much better interviewer than he is a writer; his lengthy and rambling interview with Jacques Levy about the writing of the songs on Desire is quite good, and he always makes sure to eventually bring Levy back to the subject at hand. Nick Train writes a splendid piece on the influences of Robert Johnson on Dylan’s work, particularly the songs on Street Legal. And Chris Cooper conducts a revealing interview of Dave Kelly, who was Dylan’s personal assistant on the Saved tours. Al Aronowitz’s remembrances of 1969 are problematic; his piece relating Dylan’s presence in Woodstock with the music festival that went by that name comes off as the most crass and empty form of name-dropping, but his story of Dylan’s return to performing at the Isle of Wight Festival is by turns poignant, hilarious and rivetting.

All in all, Isis is an uneven read. Completists probably already have all the issues of the ‘zine, and hardly anybody but a completist will want to slog through the whole book. Helter Skelter touts it as a reference book, but it would need a much better editor and a professionally compiled index to fit that bill.

(Helter Skelter, 2001/2004)

(Helter Skelter, 1998/2004)