Believe it or not, science fiction and fantasy used to be dominated by men. (They also used to be a lot more fluid than they are now – the genres, not the men.) Of the major writers in the area before about 1970, women can be numbered on the fingers of one hand: Leigh Brackett, C. L. Moore, and slightly later, Kate Wilhelm, Doris Piserchia, and Andre Norton, and even then, Norton’s novels were mostly juvenile fiction. Catherine Moore published her first story in 1933 and was one of the regular contributors to the pulps through the thirties. (Bracket, her nearest contemporary among the early women in fantastic literature, published her first story in 1940.) Moore also created the first female fantasy hero, Jirel of Joiry. Another of the greats of the Golden Age, Henry Kuttner, wrote her a fan letter in 1936, thinking she was a man; they were married in 1940 and thereafter worked almost completely in collaboration, using various pseudonyms, the best known of which is Lewis Padgett.

Believe it or not, science fiction and fantasy used to be dominated by men. (They also used to be a lot more fluid than they are now – the genres, not the men.) Of the major writers in the area before about 1970, women can be numbered on the fingers of one hand: Leigh Brackett, C. L. Moore, and slightly later, Kate Wilhelm, Doris Piserchia, and Andre Norton, and even then, Norton’s novels were mostly juvenile fiction. Catherine Moore published her first story in 1933 and was one of the regular contributors to the pulps through the thirties. (Bracket, her nearest contemporary among the early women in fantastic literature, published her first story in 1940.) Moore also created the first female fantasy hero, Jirel of Joiry. Another of the greats of the Golden Age, Henry Kuttner, wrote her a fan letter in 1936, thinking she was a man; they were married in 1940 and thereafter worked almost completely in collaboration, using various pseudonyms, the best known of which is Lewis Padgett.

Moore on her own highlights the process I’ve had to go through recently, as more and more reissues and new collections of the first generations of science fiction writers cross my desk – call them the Golden Age writers, but they can also quite legitimately be called the Writers of the Age of Pulp. These were people who, sometimes obsessively, pounded out stories to editors’ specifications, some of them with dizzying speed, for next to no money. We tend to look down at them, just a little, just because of that, but as we grow in our sophistication as readers and encounter them again, we begin to see some of the amazing things they were doing.

Moore, for example, in “Judgment Night,” the title story in this collection (actually a short novel), creates a tale of seduction and deceit that seems to be a fairly standard space opera, except for the almost subliminal feeling of unease that permeates the narrative, as though something threatening is going on just out of sight. Like the other stories it presented, it also portrays some pretty hard-edged ideas and not much in the way of optimism, which was a hallmark for the science fiction of the time.

Moore’s fiction is not concerned with the “idea” (concisely stated as “better living through technology”). She is concerned with personalities and the consequences of her characters being who they are. Juille from “Judgment Night” for example, although the protagonist, is not really a very nice person – spoiled, temperamental, somewhat shallow, she more than fulfills the prophecy of the gods: her instincts are wrong. In this case it means that in spite of anything she does, humanity is going to be supplanted. The grimness in the tale stems from the fact that she probably could not have done anything to stop it. (I see a very early example of the Michael Moorcock-Glen Cook strand of thought about gods and men here.)

Similarly, Morgan in “Paradise Street,” a prickly loner who hates the civilization that inevitably follows to the planets he opens up, is duped not once but twice by the same slimy crook. It’s only through the intervention of two friends who see his own worth more clearly than he does that he avoids being lynched. This is, by the way, a wonderful story, with a deeply poetic viewpoint barely masked by the mordant realism of the narrative.

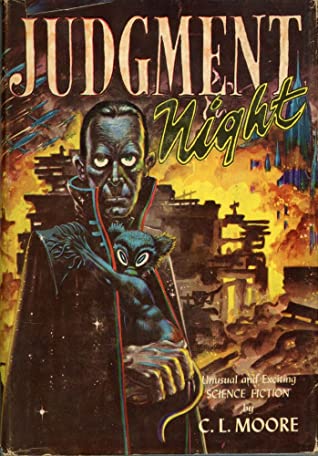

These are solid stories, not at all the hack work we tend to think of when someone mentions the pulps, and serve to fix Moore’s place as a major voice in science fiction of the Golden Age. This edition is a facsimile of the original Gnome Press edition of 1952, and it’s a trip down memory lane, from the cover by Frank Kelly Frease to the stories themselves. It’s also a good reminder that science fiction, from its earliest days, was a lot more serious than most people think, thanks to writers like C. L. Moore.

(Red Jacket Press, 2006 [orig. pub. Gnome Press, 1952])

Red Jacket Press focuses on reissues of out-of-print science fiction titles, many in facsimile.