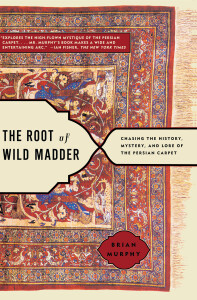

It’s hard to miss the design on the dust jacket of this book. It’s a wraparound photograph of a Persian carpet, cropped so that the selvedges line up with the top and bottom edges of the jacket and the fringes touch the edges of the front and back covers. The paper has a slightly rough texture. Of course the opaque and somewhat garish overlays of the book’s title and subtitle (Chasing the History, Mystery and Lore of the Persian Carpet), the author’s name, and the blurbs and bar code on the back cover really detract from this lovely design.

It’s hard to miss the design on the dust jacket of this book. It’s a wraparound photograph of a Persian carpet, cropped so that the selvedges line up with the top and bottom edges of the jacket and the fringes touch the edges of the front and back covers. The paper has a slightly rough texture. Of course the opaque and somewhat garish overlays of the book’s title and subtitle (Chasing the History, Mystery and Lore of the Persian Carpet), the author’s name, and the blurbs and bar code on the back cover really detract from this lovely design.

Fortunately, these dust jacket gaffes do not signal any comparable shortcomings in the contents. In fact, this is one of the most interesting non-fiction books I’ve read in a long time — so much so that I read it from cover to cover, which is not my usual practice with non-fiction. I volunteered to review it because I thought it was about an ancient craft — the making of elaborately patterned Persian carpets. Murphy’s engaging first-person narrative style, his use of active verbs and his vivid, sensual descriptions grabbed and held my attention.

For a reader who, like me, finds Persian carpets and other forms of Persian design appealing, this book offers an introduction to the culture(s) that created them. Murphy tells about his fascination with the carpets and the process by which he overcomes his discomfort at being a Westerner bargaining with carpet dealers in the places he visits. Early on, he becomes interested in learning more about the wild madder plant that is the source of the red color so predominant in many of the classic rug designs. He builds the story around his quest to find carpets made of wool dyed with madder, to observe people working with this and other natural dyes, and to encounter a field of wild madder (rubia tinctorum). With some effort and over time, he accomplishes all these goals and more.

During his travels, Murphy becomes aware of the transitions that have taken place in the production of these creations, with much of the work that once was done by nomadic tribeswomen shifting to factories of varying sizes and located in virtually every nation-state from Iran to India. During one visit to a settlement of people known as Qashqa’i, he is surprised to find that they have machine-made carpets covering the floors of their tents. One of the women explains to him that the handmade carpets are valued as heirlooms or parts of dowries, and so are not intended for everyday use. This same woman points out that knowing how to make the carpets (knotting bits of hand-spun, hand-dyed wool into a weft as its laid down) is less important to her daughters and granddaughters than learning how to read. Even in these remote settlements (I can’t call them villages), modernization is slowly taking place, and the old skills are disappearing. This phenomenon is apparently of concern to the government of Iran, which has given support to a carpet museum in Tehran and established programs at some of the colleges devoted to the study of the carpets and their history.

But The Root of Wild Madder is about a lot more than the making and selling of carpets. For example, one of the dealers Murphy meets early on suggests that he learn more about the Persian psyche by reading the poetry of Hafez, a fourteenth century mystic. He acquires a translation and starts to read it in his spare moments. While he finds the English text a bit stilted in comparison to his expectations of the original, he nonetheless becomes intrigued and begins to organize some of his trips to visit places where he hopes to learn more about Hafez and his writing.

One of these places is Mashhad, where he spends time with a group of Sufis who help him, if a bit indirectly, to think of carpets as a way of contacting the divine, much as they do when they spin. Another is Yazd, a place that Hafez is said to have visited once toward the end of his life (when you are talking about a poet who lived seven centuries ago, details get a little sketchy). Yazd is also one of the centers of Zoroastrianism, a monotheistic religion that predated Islam by untold centuries (again, the record isn’t entirely clear on exactly how long. . . .) There he visits an ancient fire temple and breathes the resinous air left by a fire that has allegedly been burning for fifteen hundred years.

Yet another is Shiraz, the birthplace and home of Hafez. Shiraz was the home of Hafez for most of his life. He is buried there, in a tomb that has become a shrine for his many aficionados. Murphy has an encounter at this spot with a young man who says he sees colors when he listens to poetry. This remark sets Murphy off on a reflection about a condition called synesthesia, where the person’s sensory perceptions all run together. This apparent digression leads him back to the color red and thus to the root of wild madder.

Brian Murphy is an American journalist who has worked for the Associated Press for over a decade. The Root of Wild Madder is his second book-length writing project. It’s evidently constructed of notes taken over a number of years of travel in Iran and western Afghanistan. He’s not a historian or an anthropologist, although many people trained in these disciplines might find the book a good read. The book includes a short bibliography organized around the chapters. There are no citations in the text, and the book contains no index or glossary, although either of these would have been a useful addition. Much of the book is about travels in geographic regions not familiar to western readers, yet the map in the front of the book is a bit too artistic and lacks important details like the names of some of the places Murphy visits.

While I was reading The Root of Wild Madder, I remembered seeing another book in the Green Man library on a very similar topic. One afternoon, when I was helping the brownies dust the top shelves, I found it again: Christopher Kremmer’s The Carpet Wars (HarperCollins 2002). Odd, I thought, this one was also written by a Western journalist (Australian in this case) and covers a lot of the same political and cultural territory.

A few characteristics distinguish the two books. Kremmer’s geographic locus is farther east than Murphy’s (his subtitle is From Kabul to Baghdad, but he actually travels as far east as Peshawar in Pakistan). His is also a bit less focused on the carpets and a bit more interested in the way that people’s lives in this region have been affected by the various wars and occupations they have experienced. He tends to be slightly less personal and more historical in his approach. And, where Murphy is on quests for poetry and religion, Kremmer is interviewing warlords. Although The Carpet Wars contains no insert of glossy colored photos as does The Root of Wild Madder, it has a much more detailed map, endnotes and a real bibliography, a glossary that runs several pages in length, and an index. These are features that appeal to the scholar in me. But then I ended up reading both books. You can decide whether either appeals to your taste, as they are easy enough to find.

(Simon & Schuster, 2005)