I suppose there might be someone, somewhere, who has never heard of Brian Froud. He was already gaining a reputation as an illustrator of books for children when his distinctive vision was brought to a wider audience through his designs for the films The Dark Crystal in 1978 and Labyrinth in 1986, both directed by Jim Henson. His first collaboration with Alan Lee, Faeries, published in 1978, set the course for his future work, which has garnered him a number of awards, including a Hugo in 1995. The rest, as they say, is history.

I suppose there might be someone, somewhere, who has never heard of Brian Froud. He was already gaining a reputation as an illustrator of books for children when his distinctive vision was brought to a wider audience through his designs for the films The Dark Crystal in 1978 and Labyrinth in 1986, both directed by Jim Henson. His first collaboration with Alan Lee, Faeries, published in 1978, set the course for his future work, which has garnered him a number of awards, including a Hugo in 1995. The rest, as they say, is history.

One thing that has always struck me about Froud’s work is that the denizens of his books are seldom pretty, which is, after all, one of the characteristics we normally ascribe to “fairies,” (however you want to spell it) especially if we’re of the Tinkerbell generation (Disney version). (Considering what Disney has become, this is a mark in Froud’s favor.) On leafing through the pages from the sketchbooks, with examples of his ideas going back thirty years, one begins to see how this happened: there are several layouts in which birds, rabbits, even horses become elves or goblins, so that the finished character ultimately has a distinctive look, but it may not be what we were expecting. (I have to make an admission here: my favorite, hands-down, of Froud’s books is Lady Cottington’s Pressed Faeries Book, a concept that was greeted with horror by an acquaintance who was besotted by fairies of all kinds when I mentioned having seen it at Borders. I thought it was hysterically funny — if you want to see heads turn, laugh out loud at a large bookstore.)

While researching this review I ran across a reference to Froud as a maker of “folklore/mythic artwork,” which on the one hand seems apt — there is that quality to his illustrations, which also fit firmly within the area of “art of the fantastic” (as long as we’re trading epithets between visual art and literature); on the other hand, I may have to stop using the word “mythic” myself: it’s becoming a catch-all. I’m willing to call Froud’s work “folkloric” in a limited sense, but I can’t ascribe it the power I associate with myth. I’m not sure what it is about Froud’s own particular brand of illustration that gives it that sense of depth and reality. Perhaps it is the uncompromisingly detailed realism of his renderings, as though they really are sketches from life. Maybe it’s simply that, if you believe the photograph on his Web site, he looks something like one of his drawings.

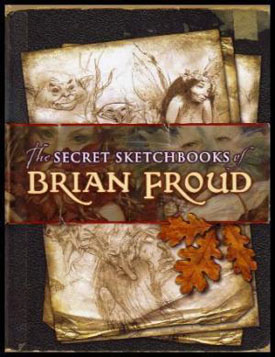

The book itself is, quite frankly, thin, both literally and figuratively. No real descriptions, no timeline, no commentary on the development of the images or of Froud’s work in general, and he is of such stature that such a view would have been welcome. I’m not asking for a Ph.D. dissertation here, but some real information would have been nice — it’s almost a truism that the only thing more interesting than an artist’s work is (sometimes, if he is articulate at all) his discussion of it. It’s a slim volume, some fifty-odd unpaginated pages of illustrations with one page of introduction by Froud. It’s really a book for fans, which, depending on your point of view, may be a good thing.

(Imaginosis, 2006)