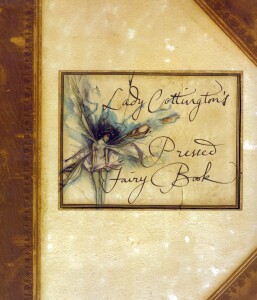

Brian Froud and Terry Jones’ Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book

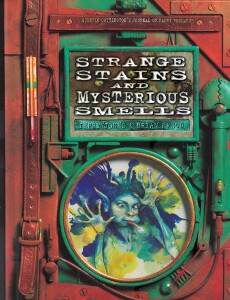

Brian Froud and Terry Jones’ Strange Stains and Mysterious Smells

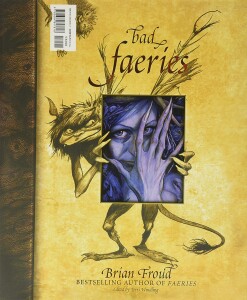

Brian Froud and Terri Windling’s Good Faeries, Bad Faeries

Brian Froud is one of those artists whose magical designs and whimsical creations stay with you long after you turn the page. Possibly best known for his design work (with his wife, Wendy Froud) on cult-favorite movies Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal, he’s also released quite a few books of his own, both alone and with various collaborators. One of the best and earliest of these is simply entitled Faeries. I was going to review it, until I discovered it had somehow, somewhere along the way, suffered severe water damage and was in no shape to be read. (I weep for this misfortune, for the book truly is a work of art.) However, I do have three of Froud’s other offerings, which thoroughly show off his talent, his whimsy, and his skill at capturing the unknown which lurks all about us.

Brian Froud is one of those artists whose magical designs and whimsical creations stay with you long after you turn the page. Possibly best known for his design work (with his wife, Wendy Froud) on cult-favorite movies Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal, he’s also released quite a few books of his own, both alone and with various collaborators. One of the best and earliest of these is simply entitled Faeries. I was going to review it, until I discovered it had somehow, somewhere along the way, suffered severe water damage and was in no shape to be read. (I weep for this misfortune, for the book truly is a work of art.) However, I do have three of Froud’s other offerings, which thoroughly show off his talent, his whimsy, and his skill at capturing the unknown which lurks all about us.

The first of these is Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book, written with Terry Jones (of Monty Python fame, also the screenwriter for Labyrinth). It’s presented, tongue-in-cheek, as a pastiche of the Victorian fairy craze, purporting to be the true journal of one Angelica Cottington, who pioneered a unique method of capturing and recording fairies in her journal. To be blunt, she lured them in, and then SQUISH! between the pages, smooshed and dried like flowers. All together … Eeeeeww. Pressed fairies. This book details her sightings and capturings between 1895 and 1912, as she grows up during the changing, romanticized times of Victorian England. She could very well be the friend of the girls who so cleverly took photographs of fairies and convinced doubters such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle that fairies were real. She was just more … hands-on.

Lady Cottington’s Pressed Fairy Book possesses a wicked sense of humor, and never takes itself too seriously, even as we follow the development of Angelica Cottington through her writings. The text is presented in an ever-improving scrawl on both pages of this faux journal. Of course, the true attraction comes in the wonderfully gruesome images Froud presents, of fairies sprawled at awkward angles, smooshed and squished with a particularly surprised look on their faces. They range from flower sprites to mosquitoesque creatures, multicolored, winged, and preserved for posterity. They’re silly, serious, beautiful, ugly, and no two are alike, demonstrating Froud’s tremendous range of inspiration and capacity for invention. As a bonus, my book actually comes with its very own pressed fairy, suitable for use as a bookmark or window-hanging, or keeping pressed. This is one of those books that earns its keep just by being so bizarre, so very different from what you might expect. The last few pages are bound together with a strip of paper for our protection, as the last fairies in the book present some T&A in their own capricious, messy style.

Froud and Jones followed that book up with Strange Stains and Mysterious Smells, ostensibly written by the good Lady Cottington’s twin brother, Quentin. He goes a step further, to detail the lives and natures of another breed of fairy altogether, transcribing “The Unnatural History of Mess-Makers and Pong-Perpetrators.” In short, while his sister was smooshing fairies in the garden, Quentin was investigating the creatures that create odd stains, smells, messes, and so forth. Froud and Jones, entirely tongue-in-cheek on this one, purport to have found this journal, and to have recreated the unusual experiments contained within, to make manifest these creatures and record them for posterity.

Froud and Jones followed that book up with Strange Stains and Mysterious Smells, ostensibly written by the good Lady Cottington’s twin brother, Quentin. He goes a step further, to detail the lives and natures of another breed of fairy altogether, transcribing “The Unnatural History of Mess-Makers and Pong-Perpetrators.” In short, while his sister was smooshing fairies in the garden, Quentin was investigating the creatures that create odd stains, smells, messes, and so forth. Froud and Jones, entirely tongue-in-cheek on this one, purport to have found this journal, and to have recreated the unusual experiments contained within, to make manifest these creatures and record them for posterity.

Thus do we meet the Bule Ketty, which inhabits the fronts of shirts and looks particularly woebegone. Thus do we learn of Whooper the Soot, a northern stain which terrorizes kirtles and skilly-pans. Thus do we understand the nature of Mai Tee Pong, which explains the unique nastiness of “Floral Air Freshener.” Thus do we meet Lucy Lilo, the invisible stain that appears only after we’re convinced once and for all that our shirt is clean, right before that big event. Meet as well George Hackenbush the Fourth, Groucho Marx aficionado and strange stain. Beware of the sprite of joss-sticks, which has no name, but affects a rather politically incomprehensible demeanor. These are but a few of the dozens of creatures penned and sketched and painted for our edification in this terrifying, fascinating expose of the world around us.

To say that Jones and Froud are having fun here would be an understatement. The text is serious in that way that only great comedians can be, keeping a straight face while tossing off ludicrous situations and laughable names and silly anecdotes with aplomb and panache. Likewise, this is an art book, and Froud goes out of his way to truly embody and envision these creatures as they might be. The art defies description, and must truly be seen to be understood. It’s a unique style, all right. Where else will you find fairies picking their noses, inhabiting ATMs, drooling or dripping mucus, or just insulting the reader? Stains and Mysterious Smells is a unique book, and I thank my lucky stars it’s not Scratch-and-Sniff as well. This is easily one of Froud’s best works, with the artist at his most inventive and most evocative, and certainly his most disgusting in some places.

Finally, we have Froud’s followup to Faeries, a thick tome entitled Good Faeries, Bad Faeries, edited by Terri Windling. This absolutely gorgeous book is Froud’s exploration of the fairy world from two distinctly different angles, and is presented as a flip book. From one side, it’s all about the good faeries who inhabit this world and other worlds. From the other, it’s all about the bad faeries. So you can arrange the book to suit your mood or your tastes, and it’ll look right either way.

Finally, we have Froud’s followup to Faeries, a thick tome entitled Good Faeries, Bad Faeries, edited by Terri Windling. This absolutely gorgeous book is Froud’s exploration of the fairy world from two distinctly different angles, and is presented as a flip book. From one side, it’s all about the good faeries who inhabit this world and other worlds. From the other, it’s all about the bad faeries. So you can arrange the book to suit your mood or your tastes, and it’ll look right either way.

Starting with the Good Faeries, we are treated to an introduction by Froud, in which he explains how the book came to be, how he’s changed, grown, and learned much in the twenty years since Faeries originally came out. We see his more metaphysical side at work, a side which helped him to later create The Faeries Oracle.

The Good Faerie half contains a brilliant, well-written essay on the history and classification of faeries. He talks of naming them, of the elements they represent, of their unusual and expressive physiognomy, of the science of the faeries, of healing, and of communication, and so forth. To try and summarize would be a crime, as this could very well be a textbook on faeries. Hey, we know so little, who’s to say he’s not right?

Then we get into the actual faeries. There are the classic flower faeries, perceptive piskys, salamanders and sylphs and undines, The Faery Godmother, The Frog Queen, the knowing faery, the morning faery, and so many more. Dozens of gorgeous, flowing, fluid, natural creatures of primal passion and elemental magic, of legend and myth, folklore and New Age belief. Some have been around for centuries, some are as new as the book itself. There’s the ghost of a mushroom and the Plymouth Rock Faery, the Angel of Spiritual Empowerment and the Gladfly, the Healing Goddess and The Green Woman. There’s even the King of Green Men himself (our patron here at Green Man) and various pixies. They are too numerous and distinct to be described by mere words.

Then we get into the actual faeries. There are the classic flower faeries, perceptive piskys, salamanders and sylphs and undines, The Faery Godmother, The Frog Queen, the knowing faery, the morning faery, and so many more. Dozens of gorgeous, flowing, fluid, natural creatures of primal passion and elemental magic, of legend and myth, folklore and New Age belief. Some have been around for centuries, some are as new as the book itself. There’s the ghost of a mushroom and the Plymouth Rock Faery, the Angel of Spiritual Empowerment and the Gladfly, the Healing Goddess and The Green Woman. There’s even the King of Green Men himself (our patron here at Green Man) and various pixies. They are too numerous and distinct to be described by mere words.

Froud’s artistic genius has matured and developed a lot over the decades. He’s not the same artist he was when he helped create the uniquely memorable characters and concepts in Labyrinth, but he’s changed only for the better.

Any one of the pieces in this half of the book could be poster-quality, easily. They’re that good, each one absolutely fitting the being it supposedly represents.

In the Bad Faeries half of the book, we run into the worst of an entirely different, very bad, lot. The introduction on this side is a mirror image of the other one, detailing another set of circumstances and beliefs to create one whole story. The essay for this part of the book details things like faery blights, defects, music, glamour, warding against the faeries, and more.

The Bad Faeries themselves are ugly, twisted, hideous, wicked, disturbing, creepy, and beautiful in their own way. There’s the Queen of the Bad Faeries, peering at us from between her twisted fingers. There’s a perfidious pook and a bigot bogey, the computer glitch and the sink faery, the dreaded Snagger (who preys on travellers and puts runs in stockings, among other crimes), and the faery of indecision. There’re the faeries of dark despair, the pang of regret, the compulsive faery. There’s even a faery for bad hair days!

These are all of the malicious, malevolent, mischievous, petty, nasty, evil, rotten things that go wrong in the world, taken from myth and legend and everyday life with equal glee. Morgana the Fey is here, as is the Out-of-the-Blue Faery (out of the blue, you remember that anniversary you forgot…) Worst of all is that fiend himself, the Buttered Toast Faery, who decides what side the toast lands on when you inevitably drop it. (There’s probably a Cat Hair Faery, which explains why they shed so much….)

If the rest of Froud’s books are good, this one is nothing short of superb in every regard, from the handsome design to the spectacular artwork inside. Froud is easily one of the best “faery artists” of this era, much like Arthur Rackham was for his generation, comparable only to someone like Charles Vess.

I can’t say enough nice things about this book. It’s a treat for mind and eyes alike.

Naturally, you can find out much more at the World of Froud.

Also, we recommend you check out Endicott Studio for more on Froud, Terri Windling, and everything we here at Green Man Review like about fantasy, folklore, and yes, faeries. (Or fairies. The spelling is up to you.)

(Turner Publishing, 1994)

(Simon and Schuster, 1996)

(Simon and Schuster, 1998)