Tiffany Matthews wrote this review.

Tiffany Matthews wrote this review.

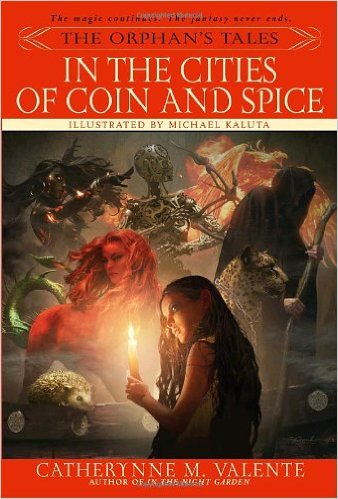

Catherynne M. Valente has quietly declared war on the pleasant lull and tawdry titillation that too often characterize contemporary fantasy fiction. Her new kaleidoscope of nested tales, In the Cities of Coin and Spice, offers the reader an experience altogether more rare and complex. Within its pages, she disdains the idea of comfortable fantasy, instead evoking the literary equivalent of gothic art nouveau — constructed of stained glass tableaux, rendered in colors of blood and twilight, sharply etched to jut from profoundly inky shadows. In this extraordinary, re-envisioned “Tale of Two magical Cities,” historical urban geographies emerge, jumbled and fractured as revealed through flashes of individual experience, related by a witch-girl who bears the stories as swarming tattoos on the lids of her eyes.

This second offering in the Orphan’s Tales collection deftly exhibits the lyrically arresting descriptions and intricately winding narrative that so memorably infused its predecessor, In the Night Garden. Common elements, shared themes, and overlapping characters indeliably mark this as a companion work, which will delight readers hoping for further revelations about their favorite stories from the first volume. However, there is no mistaking, from the very outset, that this new garden of tales is fraught with a darkness beyond the scope of mere night-time; its strange flowering has roots steeped in the gore of horror. Valente strikes at the core of even avowed literary cynics, catching readers off guard with fresh and startlingly original metaphors, then shoving her audience into a state of pervasive unease, summoned by unflinching depictions of the terrors that stalk her imagined geography: monsters of bone that devour all life, raptor-like child-murderers, undead soul-snatchers, unicorn-maimers. Treachery, loss, disillusionment, and death curdle around every twisting corner as the book opens.

I am as guilty as the next mass consumer of indulging in light and easy escapist fantasy. Struggling at first with the pervasive dread of the opening chapters, I subconsciously tried to leave the book behind; I kicked it under the bed, buried it in a pile on my desk, and left it in the car, but in the end Valente’s powerful vision insists on itself. In one yarn, a particularly sentient spider warns, “Another creature’s tale is like a web: It spirals in and out again, and if you are not careful, you may become stuck, while the teller weaves on.” These tales are a masterful tapestry, riveting readers like rubberneckers on awful scenes. While we, as readers, shiver with the boy listener in the winter garden when he protests, “I don’t like this story . . . I liked the pirates better” it is clear that Valente’s purpose is not to luxuriate in horror for its own sake. Instead, by extension, the unsettling events of the first few stories cause us to cast our collective gaze on our own real-world beasties — unchecked greed, lust, and arrogance — that we mostly manage to ignore in the mundane light of day.

In the Cities of Coin and Spice does not allow readers to drift, Zen-like, across the surface of the tales as was possible In the Night Garden. Actually, this collection more closely resembles a rollercoaster. While the opening descent into depravity is gut-dropping, the story rewards the courageous with exhilarating heights evoked by the stellar beauty of Valente’s language and the pure ingenuity of her luminously unforgettable characters. We are privileged to meet scores of fascinating creatures, from a genie of glowing cinders, a captive phoenix, and a bemused heifer goddess, to a village of amnesiac turtles, a conscious tealeaf and a troubadour manticore. What sometimes seems to be a meditation on hardship and evil also dedicates fluent poetry to honor those bright things that succor us in the most terrible places — loyalty, revelry, compassion, music, study, and love.

Valente undertakes these grand themes without sinking into cliché or redundancy. In fact, these meditations lead her to break fresh ground, as she clings less tenaciously to the rhythms of archetypal tales in this volume than the last. She has untethered her writing, allowing readers to freefall into new, wildly inventive tales that, while remaining informed by classic fantasy, transcend and even actively seek to implode it via the outright reversals that litter the text like quartz in forest soil. In one tale, a mermaid is lured by a lonely man, in another a devil tempted into bargaining for a fiddle, and elsewhere a basilisk is turned to stone.

Valente displays an endearing fascination with the unexpected, the abnormal, and the outcast. Her characters have unlovable personas like Scald, Ruin and Rend. In one story, an intriguing pair of sister bard-birds states, “We like the wrong sorts of girls. Those are usually the ones worth writing about.” Women, in particular, often comprise strange amalgamations of objects; they are built alternately of music sheets, wicker, metal, glass, fire and trees. These incongruous shapes function as a revelatory window for readers; we must squint to take in the alienness, and in so carefully examining, we recognize ourselves. This essential preoccupation with the weird and absurd births a profound sympathy for outsiders and the oppressed. Valente appears to mistrust overly rigid and predictable structures; architecture, engineering and economics are all painted as potential wonderments, twisted through the tyranny of convention into cancerous perversions. Her book draws attention to how we engineer our realities, for better or worse.

At one stage of a city’s decline, its inhabitants’ lust for wealth grows so uncontrollable that food itself is actually replaced with gems. As one of its warped residents unbearably trades the life of a child for cursed coin, she states, “. . . economy was like this, light and thick and sweet . . . I tasted it long after I could taste nothing else.” Again and again throughout the book, the dangerous compulsion of acquisition causes destruction and desecration. Tracing the decay of a society so hopelessly trammeled warns us that what glitters often has no nutritive value. This lesson inherently contains a stark portraiture of the tensions between the unwanted and the privileged. Sacrifice and abandonment thereby emerge as pivotal themes winding throughout the text. Women and children are routinely abandoned; their bodies, freedoms, and their very lives are sacrificed to satiate the hunger for lucre, which is unmasked as deriving directly from the flesh of those whom economy consumes.

Some self-referential moments examine another facet of the sacrificial theme, considering the forfeitures necessary to the nature of art. At one point, Valente seems to drop all pretenses and speak straight to the reader, asking, ‘What damage does the telling of a story play upon its teller?” In her gorgeous depiction of the marriage of a princess in a winter garden, she writes:

In all the delight at the snow, the Garden was blazing with candles and colors . . . Skirts of violet and emerald swished over the paths; shoes of clattering horn and oiled stag-skin spoiled the perfect white with footprints, like ink scrawled haphazardly upon a page of new paper.

One can almost read the regret of the author in this observation, as she wonders what pristine vision the storyteller must spoil in order to spin the tale. Perhaps she laments the fates of her characters, or the necessity of choosing from the infinite well of stories that beg to be told? Valente asks her readers, and herself, intelligent, complex questions, instead of seeking to spoon-feed us facile answers.

This book can be viewed as a compendium of the tales of cast-off children, stars who are offspring of an inscrutable universe, citizens who are birthed by dying cities, boys and girls who are the leavings of parents bereft of compassion. The wild river of narrative in The Cities of Coin and Spice follows their trials and joys, allowing readers to see how determination and hope can create beauty and redemption. Valente best describes her own undertaking, “There is a kind of poetry in metamorphosis. . . .”

The two Orphan’s Tales books together illustrate a sort of map of metamorphosis. The boy-prince listener, who from the outset represents sterile wealth and authoritarian canonical convention, begins by listening passively, against the wills of his own captors and internalized judgment, to the chronicles of a girl representing the wild voice of nature, the economically bereft, the abandoned, the sacrificed, and the overlooked. However, as she begins to recognize her own power and magic, he, too, takes a more active role, ultimately reading the stories from her eyes when she becomes unable, and taking responsibility for the narration himself. This interchange and broadened vision ultimately sets him free. In this novel of predators, prisoners, prayers, prophets, countless heroes and Tarot fools, re-union, transcendence, and liberation are the common goals. Valente’s spell draws empathy from her audience. In reading, it was necessary that I was lost, I was forsaken, and I was despondent, before the joy of the transformed characters could be truly meaningful for me. This book, a literary mechanism for immersion in the language of the soul, is no small feat; it is, instead, the work of the wise.

(Bantam, 2007)