“No hoof, no horse,” say the Worshipful Company of Farriers. “Farriery,” the craft of shoeing horses, was even more vital in the days when every mobile enterprise was dependent on horses, especially the enterprise of war. And what more famous warrior-king has there ever been than Arthur? What might it have been like to have been Arthur’s farrier? Anne McCaffrey gives an answer to this question in Black Horses for the King.

“No hoof, no horse,” say the Worshipful Company of Farriers. “Farriery,” the craft of shoeing horses, was even more vital in the days when every mobile enterprise was dependent on horses, especially the enterprise of war. And what more famous warrior-king has there ever been than Arthur? What might it have been like to have been Arthur’s farrier? Anne McCaffrey gives an answer to this question in Black Horses for the King.

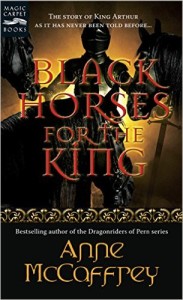

The idea for Black Horses for the King comes from historical-legendary fragments that suggest that the real “Artos” (circa 500 AD) may have imported Libyan horses from Septimania to give his mounted forces a tactical advantage over their Saxon enemies. McCaffrey spins a story in which these giant beasts are going lame from hoof problems on the soft, wet British ground, so different from the deserts where they were bred. To save them, one of Artos’ loyal hostlers invents an iron sandal to protect their vital hooves. The moral of the story is that noble knights need not be the only important actors in the Arthurian drama. Even a farrier can be a hero if he serves the “once and future King.” After all, no hoof, no horse. No horse, no knight.

The story is told from the point of view of Galwyn, a poor young man who manages to win a place for himself as Artos’ hostler and eventually as one of his first farriers. Galwyn initially catches Artos’ attention on the voyage to the horse fair at Septimania. Galwyn has a gift for languages, and Artos needs him to translate during the bartering process for the huge — and hugely expensive — Libyans. Galwyn’s experience with horses, gained before his family lost their fortune, makes him invaluable to Artos yet again, as he helps bring the Libyans safely across the English Channel.

Galwyn accompanies the horses to Artos’ horse farms at Deva, where he learns from Canyd, a wise old hostler, about a revolutionary new idea — horse “sandals.” Despite widespread skepticism, Canyd and Galwyn develop working horse sandals. In the heat of the first battle of the Glein, horse sandals keep Artos’ warriors mounted. A resounding victory occurs, due in part to these unsung heroes.

The plethora of “horsey” lore and the careful period details of Black Horses for the King kept my interest. I enjoyed the story and I learned something in the process — always a good combination. The one sour note for me was the formulaic nature of the plot. This book was written for “young adults.” Hence, like a host of other “young adult” (YA) books, it was doomed to follow a standard plot progression: a “young adult” struggles with his/her family, has a chance to prove him/herself, clashes with a peer, proves him/herself, and resolves clash with peer. Along the way, he/she develops self-esteem and learns a valuable lesson about relationships. In the case of Black Horses for the King, this standard plot seems oddly anachronistic, at times merely pasted against the incidental background of the Arthurian legend. When I was at an age to be reading “YA” books (I’ve always wondered what that age is supposed to be, exactly. Now that I have passed 30, is that section of the library off-limits? But I digress.), I was always suspicious of books that followed this pattern too blatantly. They smacked of niche marketing. In the author’s note to Black Horses for the King, McCaffrey states that she dislikes the Hollywood version of the Arthurian legend and prefers a historical Artos, a fifth century dux bellorum. In the painstakingly historical setting she creates, however, her very modern, typical “YA” plot is all the more jarring.

(Harcourt Brace & Company, 1996)