After reading the first couple of pieces in this collection, I contacted a friend who’s active in the steampunk community. “Who’s a good writer in the field?” I asked her. She was embarrassed. Really, she said, there isn’t anybody much. And her man added that steampunk is more of a life style than a literary style, a sensibility still in search of artistic expression.

After reading the first couple of pieces in this collection, I contacted a friend who’s active in the steampunk community. “Who’s a good writer in the field?” I asked her. She was embarrassed. Really, she said, there isn’t anybody much. And her man added that steampunk is more of a life style than a literary style, a sensibility still in search of artistic expression.

Which is pretty much a cut-to-the-chase summary of the introduction to this collection: “What Is Steampunk?” In case that wasn’t clear enough, the book also concludes with a series of brief essays on the subject of what steampunk is, has been, and is going to be, contributed by members of the community.

And the fact that they feel it necessary to spend so much time defining their genre is almost fatal to this book. If the stories have merit, they will explain themselves; if they do not, then being told about their background will not make them better.

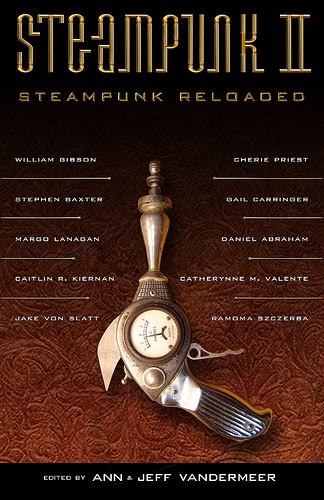

And the first few stories are nothing to telegraph home about. Opening with the weakest piece I’ve ever seen out of William Gibson, the editors follow this with a predictable tale of Dabbling In Dangerous Forces told in the forced form of a series of encyclopedia entries, which is followed, in turn, by an exceedingly unlikely alternate-history tale featuring atomic Incas in blimps conquering an Earth so far from ours that the stars are different and yet so similar that prominent names throughout history have cropped up in the royal houses and common streets of Peru and England alike . . . So far this collection is not steamy and it’s not punky, and I’m not impressed. Rehearsing the flaws of the original “roots” tales of Verne and Wells, these are tales of ideas and wonders more than of people: they are style, but they don’t have much substance.

We come up for a breath of pure steam in the disturbing atmosphere of Caitlín R. Kiernan’s “The Steam Dancer (1896)”. A steamy tale in every sense, here we get a glimpse of what things are like on the margins in a world of polished brass wonders. It’s a beautiful achievement, this story, a very human, rather squalid life offered for our perusal in terms that are neither sentimental nor cruel, managing an effect at once intimate and remote. Now there’s so much that’s peddled as artistic today simply because it’s depressing that I must stress that this tale is depressing, in a quiet sort of way… but that’s not what makes it art. What makes it art is the command of voice and personality Kiernan displays, the things she says and the things she leaves unsaid, and the fact that she can deliver this character-driven gem while still conjuring up a whole world of clanking, steam-driven marvels in the background, almost all through hints and allusions. This story lingers. I hope it gets a good deal of attention; it deserves to.

“Machine Maid”, by Margo Lanagan, is the start of a run of pretty decent tales. It’s a “spoiler” piece, so I’ll spare whatever surprise value it may have and leave it at that . . . and for quite different reasons, it isn’t easy to say much about “The Unbecoming of Virgil Smythe”, a contribution credited to Ramsey Shehadeh but which was probably written in reality by Philip K. Dick and Rudyard Kipling in collaboration. A short piece in graphic form, Sydney Padua’s “Lovelace & Babbage: Origins, With Salamander” is unusual in the degree to which it is founded on the lives of two real people; it is even more unusual in that it includes its own footnotes, and by the time you get around to the fact that these five pages of comic-book footnotes are a prologue to a piece of Victorian science fiction that is itself only two panels long . . . you wind up with a tale that demands to be called quirky, so I will. It’s quirky. Padua’s art is characterised by a deceptively sketchy line that lets the eye glide over some pretty solid costume research and expressive faces. A better-than-average sense of period dialogue is juxtaposed with anachronism to good effect throughout. Several of my favourite moments in the entire collection lurk within this brief slice of wry.

The best stories in Steampunk II are simply science fiction and fantasy tales containing elements – sometimes no more than window dressing – of 19th-century technology or social history; the worst stories are those which very earnestly Try To Be Steampunk. Worst of all is a sort of “jam” story, “The Secret History of Steampunk”, which was probably a great deal of fun to work on, in fact, but which loses a great deal in translation to the published page, full of in-jokes and cunning references to people and events for which (I’m guessing) you had to be there. I wasn’t; I suspect most readers weren’t there either.

Most of the writers in this collection who attempt the tones of formal Victorian dialogue, journalism or correspondence do not handle it altogether convincingly: and for many of the same reasons, it probably should not be surprising that a majority of these pieces either offer us an age of steam where women hold an equal place with men, or — failing that – take us into the life of some woman who for one reason or other must break the mold. Most of the best stories in the collection are by women. Make of all that what you will.

Perhaps half this book is first rate; the other half is . . . not. If this is the shape of steampunk literature today, overall I’d say it needs a second draft. Back into the laboratory with you, and don’t you come out until that whole thing’s shiny.

(Tachyon Publications 2010)