Diane McDonough wrote this review.

Diane McDonough wrote this review.

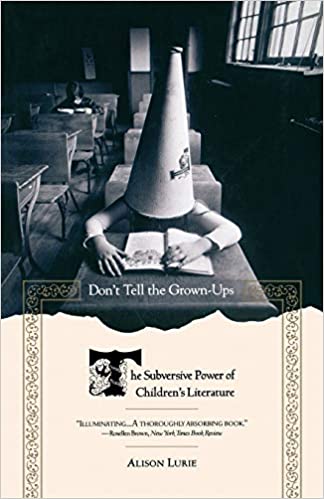

If you ever wondered at the appeal of Kate Greenaway’s winsome lasses with their wispy Empire gowns, if you’ve ever contemplated the universal charm of Winnie the Pooh, if you’ve ever tucked The Secret Garden into your suitcase to peruse on vacation, then Alison Lurie’s book of essays is for you.

Complete with biographical tidbits and juicy gossip about some of the icons of childhood’s literature, Lurie explores the themes of subversion in the books loved by children, introducing lots of background to support her theory. Best of all, she writes of the Bastable children and E. Nesbit, prompting an immediate reading of The Wouldbegoods — but, I digress.

Lurie argues that certain aspects of children’s literature, not necessarily that ordained by the status quo, reinforce primitive cultural aspects of childhood. To support her theory, she goes to the stories that “were the sacred texts of childhood, whose authors had not forgotten what it was like to be a child. To read them was to feel a shock of recognition, a rush of liberating energy.” The author explores fairy tales, Winnie the Pooh, and J.R.R. Tolkien with an analytical yet affectionate eye that belies the serious scholarship and research underpinning each essay.

It is biographical data that shines in each essay. I shall never again look at Kate Greenaway’s girls without hearing the plaintive plea of John Ruskin, the Victorian literary lion. The great man wished to peek under the little imaginary frocks of Greenaway’s bucolic children. When Greenaway presented him with her illustrations for Browning’s “Pied Piper of Hamelin,” he positively whines at the overabundance of garments on the girls: “I think we might go to the length of expecting the frocks to come off sometimes.”

As Lurie details the relationship between the plain little illustrator and the great author, whole volumes of proper Victorian thought shudder and collapse. She chronicles the relationship between Ruskin and Greenaway, highlighting the dichotomy in the shy little illustrator’s life as a middle-class spinster attempting to support her parents while attempting to please the great man. Ruskin freely criticized Greenaway’s work, all the while asking for more drawings, never offering payment for any of her work.

Each essay comes back to the main point Lurie is emphasizing in this collection: the delight certain authors bring to generation after generation of children and how this universal ability to delight children comes from some tragic flaw in each author. Like Greek tragedy, the recurrence of frustration, pathos, and sexual degeneracy is emphasized as the catalyst for some of the most fun literature ever written. Sure does make you say “hmmm.”

(Avon Books, 1990)