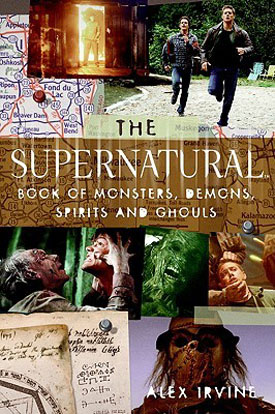

I seem to be faced with another one of those television spin-offs, this time from the series Supernatural, about two brothers, Sam and Dean Winchester, who hunt demons and other nasty customers not entirely of this world.

I seem to be faced with another one of those television spin-offs, this time from the series Supernatural, about two brothers, Sam and Dean Winchester, who hunt demons and other nasty customers not entirely of this world.

For those who, like me, may not be familiar with the series, the basic premise is as follows: Dean and Sam’s mother was killed by a demon when Sam was a baby; his girlfriend is killed the same way. When their father is missing while on a “hunting trip,” the brothers decide to go after this thing themselves.

Alex Irvine has taken this basis, and the various creatures the brothers encounter, drawn from myths, urban legends, and folklore, and turned it into a “bestiary of the unnatural,” which pulls together lore on supernatural beings from all over the world, with sources ranging from Thomas Aquinas to the Eddas. The whole thing is told by Sam and Dean in a conversational narrative style that, one assumes, reflects the style of the characters in the show. (At least, I assume — given Irvine’s skill as a writer, it would be silly not to.)

Some of the entries might strike one as odd in a book devoted to supernatural creatures, such as the chapter on the Vanir in the section on spirits. That chapter, as it happens, I found particularly interesting, not only because of my own interest in Norse mythology, but because Irvine has not only pulled in an episode from the series as a basis, but tied it to the classic descriptions of the Norse gods, examples of pre-Christian religious practices among the ancient Scandinavians and Celts, and findings from archaeological and anthropological research in the twentieth century, with the result that the chapter leaves one with a whole new take on scarecrows. (The section also includes entries on “The Woman in White,” various harbingers of death, a whole slew of water and land spirits, and a few urban legends.)

“Monsters” is, as might be imagined, a grab-bag, running through various forms of otherwise unclassifiable critters, including golems, various shapeshifters (including bearwalkers, puca, and of course, werewolves), homunculi as created by various medieval alchemists (although these sound relatively unthreatening, given their relative fragility), and few other sorts that are, thankfully, relatively uncommon.

Irvine also displays a good facility with finding correspondences from different traditions. The section on “Ghouls, Revenants, et cetera,” for example, includes not only the usual examples of ghouls from European traditions, haunting graveyards and eating corpses (including a discussion of their origins), but ties in examples of the undead from ancient Roman, Nordic and Afro-Caribbean sources as well — shtriga, draugr, vampires, and zombies (along with instructions on how to dispose of them), and more — as the book notes, there are always more.

The section on demons is particularly rich, since a demon is the Winchesters’ main target. And again, Irvine has drawn together from Hebrew and Islamic sources, as well as early Christian writers, and built around the central focus of the series: the search for the demon that killed their mother and Sam’s girlfriend. This final section provides a neat wrap-up for the entire book, and brings it full circle (although it never really left) — it’s a strong finish that builds in depth and immediacy.

And to cap it all off, there is an appendix on the magical uses of herbs, and a second on European demons, listing their names and attributes, and again drawn largely from early sources. (The appendices, by the way, match what I’ve found from my own research, so I can state confidently that he’s not making it up.)

In addition to being an entertaining read, even if you haven’t seen the TV show, Irvine has provided a good resource for those interested in supernatural beings and wrapped up a lot of information in an engaging narrative.

And wouldn’t you know — Supernatural is currently available for streaming on Netflix.

(Harper/Collins, 2007)