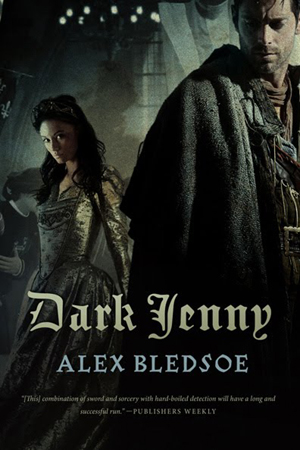

What do you get when you mix the legend of King Arthur with the detective fiction of Raymond Chandler? It seems you come up with Alex Bledsoe’s stories of Eddie LaCrosse, sometime mercenary soldier, sometime hardboiled detective.

What do you get when you mix the legend of King Arthur with the detective fiction of Raymond Chandler? It seems you come up with Alex Bledsoe’s stories of Eddie LaCrosse, sometime mercenary soldier, sometime hardboiled detective.

In Dark Jenny, Eddy, as seems so often to be the case in these kinds of stories, is in the wrong castle at the wrong time. Hired for spouse-tailing duty, he’s witness to a murder by poisoned apple, and makes the mistake of trying the help the young knight brought low by the purloined fruit, which has the effect, in what passes for reason in the minds of the other witnesses, of making Eddie the prime suspect. What makes it particularly knotty is that the apple was intended as a gift from Queen Jennifer Drake to a Knight of the Double Tarn, Sir Thomas Gillian, who also happens to be the King’s cousin. That makes Jennifer the other likely suspect, but of course, that’s not the case, either. In fact, it’s all part of a plot by King Marcus’ half sister, Megan Drake.

Dark Jenny is, in effect, a retelling of the Arthur legend — at least the grimmer parts — in a dark-edged fairy-tale setting. All the elements are there — the King’s half sister, somewhat of an enchantress; a bastard son born of incest; a band of loyal knights riven with dissension over the murder; the Queen’s champion, rumored to be her lover as well, in self-imposed exile on his own estates until called upon the defend the Queen’s honor. There’s a wild card that I’m not going to tell about because the whole plot (in both senses) hinges on it.

Does it work? Pretty well, although fans of the high-heroic version of the Arthur cycle are likely in for a shock. And the diction sometimes jars. It’s a matter of small things, a form of address here and there more than anything else, but it sticks out and it shouldn’t. And given the fantasy-standard setting and the seamy alleyway situations, Bledsoe does a credible job of pulling it together, although I must admit to a slight discomfort that I can’t quite put my finger on. Although I try not to have my own expectations about a work I’m approaching, there are, especially in genre fiction, certain justifiable expectations that the author has to deal with. And if you’re going to be blending genres, it has to be done seamlessly, and I’m not sure that’s quite the case here.

The major plot twist is a doozy, and if it were Raymond Chandler — well, Chandler never would have done something like that, and I’m surprised I don’t object to it more, but Bledsoe does make it credible, if only barely.

In spite of my reservations, though, it was a fun read.

(Tor Books, 2011)