Rebecca Scott penned this review.

Rebecca Scott penned this review.

Magic is the art of producing changes in consciousness in conformity with will. – Dion Fortune

A half-wit boy in the Neolithic period is abandoned by his people upon the death of his mother. A sociopathic woman is shown a glimpse of a world wider than she had thought possible. A hunter whose entire village vanished muses on his two families. A Roman finds truth and lies on a dark hilltop. A crippled nun lives the death of a martyred saint, and does not believe the vision comes from heaven. A Crusader builds a round church, hoping to curry favor with a new order of holy knights. A conspirator in the Gunpowder Plot muses on his own death, and his father’s follies. A lecherous judge is haunted by the language of angels. Two witches, the last to suffer this punishment in England, burn at the stake. A poet rambles through the countryside, history, and his own mind. A cheeky suspenders salesman tells his tale while awaiting the jury’s verdict. An author haunts the town that haunts him.

In Northampton.

A leg is wounded. A boy, or a hog, or a man, or a woman, is offered in burnt sacrifice. An enormous black dog that is not a dog points the way. A severed head watches. A fire burns on a hilltop. The images whirl, kaleidoscopic, through a dozen stories, through the landscape of Northampton. They fill me, and the words fill me, and I feel pregnant with them. Not, perhaps, a conventional way to discuss a book I’m reviewing. But it’s not a conventional book.

Oh, okay, I’ll try …

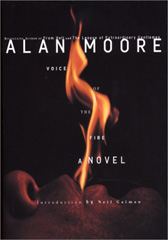

If Voice of the Fire has a protagonist, it must be Northampton itself, because this is the story of the formation of the mythology of that place. It is a geological study of the strata of the collective unconscious of the area. Each of its twelve chapters is the first-person story of an individual who crystallized into the forming stones in the hill of tales, whose bodies fed its grass and trees. Their histories wind through that of the land, bringing us closer and closer to the present day.

Each of the chapters includes a full-color plate, a photographic character portrait by Jose Villarrubia (who contributed to the very fine graphic novel Veils). These glow softly, and have a painterly quality about them that makes even the grimmest a gem. Yet this is a text novel, not a graphic novel, and the words are the things. Very fine words they are, too: “Trust in the fictive process, in the occult interweaving of text and event must be unwavering and absolute. This is the magic place, the mad place at the spark gap between word and world.” The language is vivid, graphic (sometimes too graphic for someone who reads while eating). Each chapter, each story, has a distinct voice, radically different from the others.

Not all of these voices are easy on the mind’s ears. If, as Neil Gaiman says in the introduction, quoting Alan Moore, quoting Charles Fort, “One measures a circle starting anywhere,” the reader might be forgiven for wondering why Moore began his measurement at the most difficult point. The narrative of the boy in “Hob’s Hog” is an uphill struggle to read, owning as it does only one tense, one form of any pronoun, one word for both food and thought, and a most peculiar grammar. Yet this chapter belongs where it is, and rewards the perseverance of the reader with the view from the top of the hill. Don’t be put off by the steepness of the language of the first chapter, nor its length. It is a crucial feature of the landscape.

The rest of the chapters are easier going, but watch your footing. There are traps of thought and image for the unwary.

This book is a work of magic, in Fortune’s sense of the word. This work both presaged and paralleled a change in Moore’s consciousness during the five years in which he worked on it. He became like one of his own characters, studying magics and mysteries, until I’m sure he’d forgive me for picturing him with the antlers bound to his brow, his skin covered with crow tattoos, the shaman of his town. If you let it, it will work a change in your consciousness, too, though whether in conformity with your will, or Moore’s, or that of the fire or the shagfoal, only time will tell.

So come, climb this hill of tales in the night of myth, draw close to the flames, listen to the voice of the fire, and let it work its spell in you.

(Top Shelf, 2003)