It is sometimes very difficult to get past the packaging of recordings to the substance (if there is substance, which is not always the case), particularly when dealing with new age music (“new age” being one of those categories we use for things we can’t quite fit anywhere else, similar to terms such as “psychology” and “photography”). If you really want to turn me off, tell me your music is going to take me to a higher spiritual plane — another of those truisms I can hardly believe anyone has the gall actually to say out loud, much less write down for publication. Why else do we listen to music, after all? What it boils down to is that, when dealing with a work of art of any variety, I seldom care about the artist’s intentions unless the work itself is engaging enough to make me want to learn more. (And frankly, if I can’t get some sort of handle on what the artist was up to by looking at the work itself, we’ve got a real problem.)

It is sometimes very difficult to get past the packaging of recordings to the substance (if there is substance, which is not always the case), particularly when dealing with new age music (“new age” being one of those categories we use for things we can’t quite fit anywhere else, similar to terms such as “psychology” and “photography”). If you really want to turn me off, tell me your music is going to take me to a higher spiritual plane — another of those truisms I can hardly believe anyone has the gall actually to say out loud, much less write down for publication. Why else do we listen to music, after all? What it boils down to is that, when dealing with a work of art of any variety, I seldom care about the artist’s intentions unless the work itself is engaging enough to make me want to learn more. (And frankly, if I can’t get some sort of handle on what the artist was up to by looking at the work itself, we’ve got a real problem.)

(Sidebar: It strikes me that in this respect, new age is the polar opposite to the high art of the eighties and nineties, so firmly based on deconstruction and the absence of “author.” It was, quite honestly, an art based on criticism, which became suicidally self-referential. Perhaps it’s just that we need that particular presence, the artist as an identifiable persona who stands behind the work, someone who is not only an observer and commentator with a particular talent and particular quirks, but is also, in some measure, Everyman, so that we also become participants in the act of creation.)

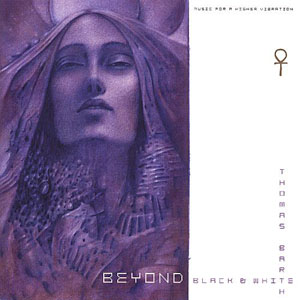

Thomas Barth seems to attach great significance to the fact that Beyond Black & White was recorded in a room containing thirty other pianos. He calls it “holistic resonance.” He also claims that it was “a successful attempt to transform vibrations going beyond the audible spectrum.” Frankly, I don’t know how a listener can tell, or why it matters. And there, perhaps, you have the root of my problems with so much new age hype: no matter how serious or sincere, it sounds like posturing, if not absolute wild-eyed gibbering. And all too often it is an excuse for avoiding any intellectual rigor.

And now that I’ve gotten past the packaging and over my temporary dyspepsia, about the music:

Barth is a fluent and sophisticated performer — his renderings are seamless, and the music itself is perfectly charming. I can’t vouch for the “holistic resonance” — there is indeed resonance here, but to my ears it could as easily be an artifact of the recording process as anything else. It does help the sound, but then, resonance always does.

The songs themselves, while certainly approachable and often beautiful, could in many instances benefit from longer treatments — development of some of these ideas would not be at all inappropriate. As they stand, they are solidly constructed works, but too often I felt there should be more to come, that what was behind this music deserved more complete investigation. Barth has the technique and the training — his musical education, which started at age eight, included not only learning Bach and Beethoven, but studying with such teachers as Herbie Hancock. And, by this measure alone, I can’t fault Barth for the philosophical underpinnings of his work — although they are perhaps better stated through the music than through words.

It’s not music to sit down to for serious listening, which is unfortunate — it could be. I think, based on this recording, that the talent and vision are there. Barth becomes one of those artists who is selling himself short: don’t promise to take me to a higher plane until you are making full use of the resources available to you in the here and now. New age is home, in record stores at least, to a number of composers and performers who have a great deal of substance to them — Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Harold Budd, to name just a few off the top of my head — and who are actively exploring new forms, new modes of expression in a time when our traditional forms — the symphony, the concerto — no longer serve. Although Barth’s Beyond Black & White is pleasant, and certainly a collection that I will keep on hand — it’s definitely a cut above most new age — one can’t escape the feeling that it could be so much more.

(Diversity Recordings, 2003)