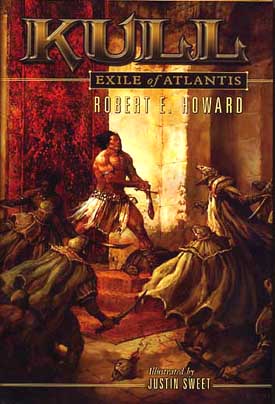

I’m sitting here somewhat red in the face at having to admit that, though a long-standing aficionado of heroic fantasy, I’ve never read anything by Robert E. Howard. It’s an appalling failure on my part, happily now rectified by the publication of Kull: Exile of Atlantis by Subterranean Press, continuing the work of Wandering Star in the UK.

I’m sitting here somewhat red in the face at having to admit that, though a long-standing aficionado of heroic fantasy, I’ve never read anything by Robert E. Howard. It’s an appalling failure on my part, happily now rectified by the publication of Kull: Exile of Atlantis by Subterranean Press, continuing the work of Wandering Star in the UK.

I’m delighted to have this volume, if for no other reason than that it blew my expectations out the window. (Expectations — I try very hard not to have any, but it does happen.) One reason I’ve avoided Howard is that I had a mental image of cartoon characters having outlandish adventures rendered in prose edging toward the ultraviolet. Don’t ask me why — I honestly don’t know. Happily, not only is Howard’s prose eminently readable — he was, when all is said and done, a fine writer — but Kull, arguably the prototype of the modern fantasy antihero, is a fascinating character. What is special about Howard’s work, as pointed out by Steve Tompkins in his intelligent and insightful introduction to this volume, is that Howard was creating the genre that became what I’ve begun calling “fantasy noir” — I can now trace a line of descent from Kull to Conan, Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser to Elric to the Black Company to the Bridgeburners that is tidy enough to make even me happy.

Tompkins is at pains to point out that Howard did not create heroic fantasy. He cites Lord Dunsany’s The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth of 1910 as a key antecedent, but I tend to think back to things such as the Arthurian stories of Chrétien de Troyes and his contemporaries, when I’m not stretching back to Gilgamesh and Volsungasaga. What is notable about Howard is the introduction of naturalistic narrative into tales of fantastic adventures, which has become the standard for heroic fantasy, and his creation of a universe larger than a single story: he began the fantasy series, when it comes right down to it, complete with ongoing characters and locales. (In fact, Howard created a framework of history and prehistory that includes not only Kull but Conan as well as their worlds.)

This collection presents the complete Kull stories from the 1920s, including sketches and unfinished fragments, taken in many cases from Howard’s own typescripts. They are arranged to provide a chronological narrative of Kull’s life from his beginnings as a youth in Atlantis (an untitled story published after Howard’s death as “Exile of Atlantis”) to his reign as King of Valusia, beginning with the first published Kull story, “The Shadow Kingdom,” and continuing on through the rest of Kull’s adventures (including his first encounter with the wizard Thulsa Doom, who is a treasure if for no other reason than his name). In spite of his barbarian beginnings and propensity toward solving problems by physical means, Kull is given to fits of introspection that generally land him in trouble. It’s a world peopled by sly, plotting courtiers, malevolent wizards, barbarians of uncertain temper, and creatures native to other planes that hold no love for Kull or his fellows. Howard creates a rich, vibrant world that takes on a kind of luminosity rare in any kind of fiction.

The volume also includes a set of fragments collectively names “Am-ra of the Ta-an,” early efforts that played a key role in the development of Kull, along with drafts of three stories included in the book. An added treat is the Appendix on the “Atlantean Genesis” by editor Patrice Louinet (who deserves thanks for the clear and sensible presentation of these stories) that details the origins of the Kull stories. There is as well a section of notes on the original texts, preceded by a comment justifying this volume as the definitive edition of these stories.

This is the kind of volume that one it tempted to assign to scholars, but the stories are too much fun to limit their audience to academia. I’m looking forward to more.

(Subterranean Press, 2008)