Joseph Haydn, the composer who did as much as anyone, and more than most, to create the style we know as “classical,” was also one of the wittiest artists of a witty era. He also created some of the most profound music of the time, reaching through a highly artificial style to reach emotional truth. In Orlando Paladino we get both the wit and the emotion.

Joseph Haydn, the composer who did as much as anyone, and more than most, to create the style we know as “classical,” was also one of the wittiest artists of a witty era. He also created some of the most profound music of the time, reaching through a highly artificial style to reach emotional truth. In Orlando Paladino we get both the wit and the emotion.

The libretto to what Haydn called a “heroic-comic drama” was, like so many romantic stories from the Renaissance on, based on an episode from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, the great Italian epic comedy that tells of the Frankish knight who goes mad and is cured. Eventually. Sabine Gruber, in her notes to this recording, calls it “the mother of fantasy stories,” which, while debatable, gives an idea of the riches plundered by librettists and playwrights for two hundred years and more.

Haydn wasn’t actually supposed to write this opera. His task was to produce Pietro’s Guglielmi’s Orlando for an impending visit of the Grand Duke Paul of Russia to Prince Esterhazy, Haydn’s patron. Perform a ten-year-old work for the crown prince of all the Russias? Never! Haydn wrote a new work from the same libretto. (The Grand Duke was a no-show.)

This is an outrageous work — outrageous in its story, anyway: Orlando is in love with Angelica, a princess of Cathay, who in turn is in love with the Saracen warrior Medoro (who has a tendency to faint when the going gets tough). Balked, Orlando goes mad, turning into a ravening beast. Angelica seeks the help of her good friend Alcina, who also happens to be a good fairy. Alcina, who is, among her other attributes, what we would call today a street pharmacist, brainwashes Orlando with a little help from some handy herbs. However, they all find it a little harder to deal with Rodomonte, another Saracen who has issues with Christians, especially Frankish Christians. There are also shepherds cavorting around between the bouts of mayhem, and not surprisingly, perhaps, Charon, boatman of the Underworld, makes an appearance.

It all makes sense when you’re listening.

Haydn took full advantage of the story, although this is one that rewards close attention to the libretto. He has no compunctions about working the music against the action, although unless one is familiar with the eighteenth-century musical idiom, one can miss some of the fun. There are places where it’s sort of like a classical Keystone Kops. Lots of fun. There’s also a lot of great music.

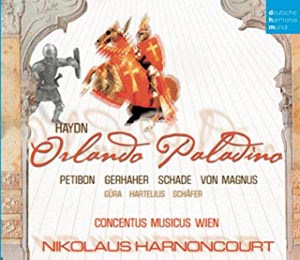

The recording is enhanced by a group of accomplished soloists who not only shine in their solo passages, but turn in some beautiful ensemble work. Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Concentus Musicus Wien are among the foremost ensembles for music of the period. All in all, while it may not be part of the basic library of classical music, it’s a recording that definitely deserves a place in any collection.

Personnel: Angelica: Patricia Pettibon, soprano; Rodomonte: Christian Gerhaher, baritone; Orlando: Michael Schade, tenor; Medoro: Werner Güaut;ra, tenor; Licone: Johannes Kalpers, tenor; Eurilla: Malin Hartelius, soprano; Pasquale: Markus Schäaut;fer, tenor; Alcina: Elisabeth von Magnus, mezzo-soprano; Caronte: Florian Boesch, bass; Concentus Musicus Wien, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, dir.

(Sony BMG Music Entertainment, 2006)